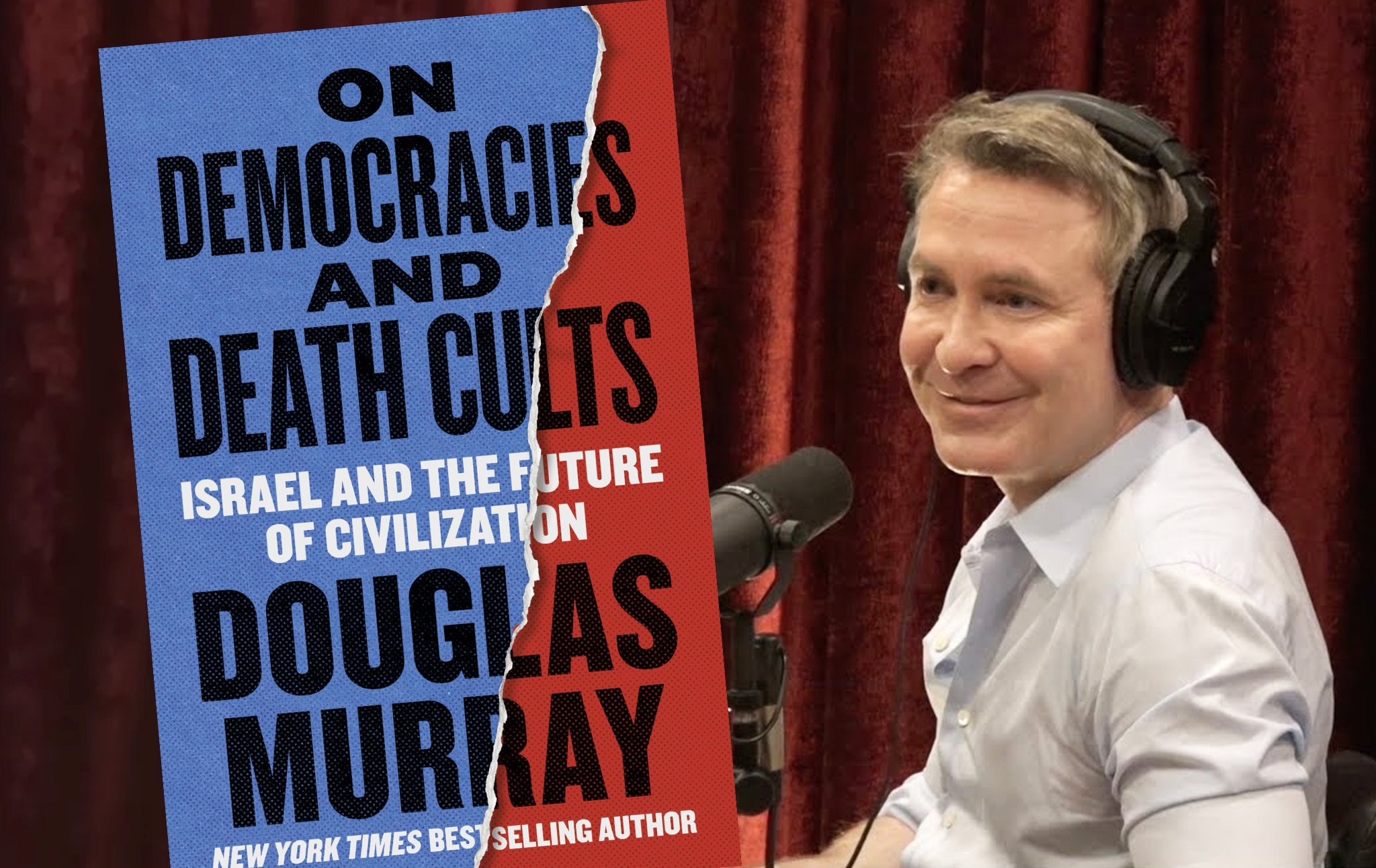

Douglas Murray’s On Democracies and Death Cults, an account of the Israel-Palestine conflict, accuses pro-Palestine protesters of being pro-“death” and argues that Israel is a Western outpost against barbarism. It has been hailed as a “book of monumental significance” and even “one of the most important books ever written” by aTimes of Israel reviewer. Another reviewer says Murray “combines deep knowledge and sparkling intellectual capability with a confident appearance.” President Donald Trump has called it a “powerful read from a Highly Respected author” and says the “Book serves as a strong reminder of why we must always stand up for America, and our great friend and ally, Israel.” (Idiosyncratic caps in original, obviously.) The book is high on bestseller lists in both the U.S. and U.K. Murray has also been appearing on popular podcasts to promote his book, with an appearance on Joe Rogan’s show racking up 4.2 million views on YouTube so far. In Murray’s episode of the Rogan show, one of the central topics of discussion was the question of expertise: Who has it? Who should be listened to? Murray was in conversation with the libertarian comedian Dave Smith, who has strongly criticized Israel. Murray was skeptical that a comedian like Smith, who has never been to the Middle East, should be listened to on Israel-Palestine. He also criticized Rogan’s decision to interview figures like Nazi-sympathizing podcaster Darryl Cooper and Pizzagate conspiracy theorist Ian Carroll. Murray argued that expertise on a subject is important and people shouldn’t spout off about things they aren’t deeply grounded in. “I think authority matters,” he said. He criticized those who say “I’m not an expert on this, but I’m gonna spend my time talking about this thing.” Rogan countered that just because someone is an expert doesn’t mean they’re right, and just because they’re a comedian doesn’t mean they have nothing insightful to say. On Democracies and Death Cults certainly provides evidence for Rogan’s position over Murray’s. Murray, the “expert,” is out of his depth. The book demonstrates why we should be skeptical of those who loudly trumpet their superior expertise. Murray may have spent time in the region, but his book is still full of deliberately misleading propaganda and even outright serious factual errors in need of correction. On Democracies and Death Cults is an effort to frame the Israel-Palestine conflict as a good-versus-evil struggle in which Israel (the goodies) are defending themselves and Western civilization from Palestinians (the baddies*). I am not oversimplifying or being unfair to Murray here. He defends his use of a framework of lightness versus darkness against those who think it’s “too reductive.” “The fight between good and evil may seem too Manichean for some,” he says, but those who “search for endless subtlety and limitless understanding” are “missing out on one of the greatest divides of all.” “Evil does exist as a force in the world,” he writes, and it’s “the only explanation for why certain people do certain things.” The Arab-Jewish conflict in Israel-Palestine has been going on for over a hundred years, and no serious scholar of the conflict frames it as a war between good and evil. In fact, it is in large part a territorial conflict between two groups both fiercely dedicated to the land. As Israel has converted more and more of historic Palestine into a Jewish state and kept the rest of Palestine under a repressive occupation, Palestinians have resisted, often with violence, which has been met with even greater violence in response. There have been abhorrent acts committed by both sides, although the death toll is much higher among Palestinians, and there is a substantial power imbalance in the conflict. Palestine is much poorer and less well-armed than Israel, which spends $46 billion on its military annually, has F-35 fighter jets and a nuclear arsenal, and has long had the support of the leading global superpower, the United States. (For more background on the conflict, see the Israel-Palestine chapter ofThe Myth of American Idealism,the book I co-authored with Noam Chomsky.) Douglas Murray does not wish for his readers to think of the conflict as complex, or to let them think for a moment that the Palestinians may have some just claims. To avoid giving any impression of moral complexity, the book mostly stays focused on the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks on Israeli civilian communities and military bases by Hamas. Murray portrays in graphic detail the horrendous crimes committed against residents of kibbutzes near Gaza and at the Nova music festival, producing haunting testimony from survivors about the atrocities they witnessed. He visited the sites of massacres, spoke with witnesses, and recounts the extraordinary heroism of people who tried to save their loved ones, or perfect strangers, from being killed. He shows the harrowing task facing those who had to clean up after the killings, and at the site of the Nova massacre he saw “the huge bags of ash that was all that was left of these young people.” As an account of the Oct. 7 attacks, Murray’s book is well-written and moving. When he is telling these stories, he wisely refrains from editorializing, letting the victims’ words speak for themselves. Murray’s work fails, however, when he tries to make it an argument about the Israel-Palestine conflict as a whole. Murray believes that the Oct. 7 attacks themselves tell the story of the conflict: Israelis defend themselves, and Palestinians mercilessly attack them. “Sometimes a flare goes up and you get to see exactly where everyone is standing,” he writes at the outset. Oct. 7, he suggests, is that “flare,” and as such it illuminates the basic dynamics of the conflict. “The story of the suffering and heroism of October 7 and its aftermath is one that spells not just the divide between good and evil, peace and war, but between democracies and death cults.” But it’s only possible to tell a story about “democracies and death cults” by singling out this one monstrous attack and ignoring everything that came both before and since. So Murray does not discuss the beginnings of the Israel-Palestine conflict. He does not talk about the Nakba, the occupation, the blockade, or the settlements. This allows him to pose as mystified by the fact that anyone could be critical of Israel. “There seemed to be a notion abroad that there was something seismically wrong with Israel,” he says, without discussing the voluminous literature, from human rights reports to books of historical and political analysis, that explains precisely what critics find wrong with Israel. He does say that Israel is called an apartheid state, but he addresses this by pointing to the fact that some Arab Israelis work in professional occupations and serve in the Knesset. “The Arabs of Israel have done exceptionally well in the past eight decades,” he writes. Instead of engaging with the extensive documentation of an oppressive two-tiered system that has been provided by human rights organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and B’Tselem, Murray points to a couple of statistics about Arab life within Israel’s legal territory, none of which refute anything that the human rights organization have claimed. (Notably, he does not address the Occupied Territories, where the situation is arguably even worse than South African apartheid was.**) By leaving out any discussion of the actual factors driving Palestinian criticism of Israel, Murray is left with the explanation that it’s essentially all the result of antisemitism. “When civilized people cannot hate the Jews for their religion or their race, Jews can be hated for having a state—and defending it.” The Arab world has simply “proved itself unable to tolerate Jews,” he points out, leaving out that much of the grievance against Israel in Arab populations is linked to the very specific project of colonizing a land regarded as holy and turning a majority-Arab territory into a Jewish state. Murray finds the student protests against the destruction in Gaza to be little more than a mixture of ignorance and bigotry (the “pro-death-cult movement”). He attempts to prove this by highlighting the most extreme pro-Hamas statements made by anyone who has shown up at a protest, while all but ignoring what the protesters are actually protesting about, namely the obliteration of entire cities; the destruction of mosques, schools, and hospitals; the blocking of food aid; the seizure of land; the displacement of most of the Gazan population; the mass killings of women and children; the shooting of paramedics and journalists; and a body count that may be well be north of 100,000. Protesters are, of course, partly motivated by their outrage at the deaths of people like Hind Rajab and Refaat Alareer, or the killing of entire families in targeted home bombings. Murray does not report having conversations with demonstrators, although he does interview Benjamin Netanyahu. He does not want to know the protesters’ perspectives. He doesn’t need to, because he is convinced they are death-worshiping antisemites. On Democracies and Death Cults is an exercise in selective empathy. Murray is caring and understanding toward those who saw the horrors of October 7. But he has no interest whatsoever in the stories of Palestinians who have seen their children shot in the head by the IDF, or the children who wander the streets of Gaza in search of their dead parents. These people might as well not exist. At times, it seems as if Murray is actually putting in substantial effort to avoid hearing a Palestinian perspective on the conflict. For instance, he visits an Israeli prison where Oct. 7 attackers are being held. He looks at them and thinks about them a bit but, astonishingly, does not recount actually trying to have conversations with them. He says he "came face to face" with them and "was allowed to go into the cells and see the terrorists for myself" but apparently he just looked at them: “I suppose that you look at people like this in the hope that you might see something in them. What is it? Remorse? Evil? I spent hours in the prison that day, and although I saw people I knew from the atrocity videos, there was nothing to learn from them. They had decided to live their lives with one ambition—to take away life.” It is a shame that Murray decided not to talk to the Palestinian prisoners. Perhaps he was afraid that if he did so, he would learn something from them, something disturbing that he didn’t want to entertain the possibility of. They would have seemed more human. Perhaps these encounters would have unsettled his conviction that evil is something that “just descend[s] on the world.” Maybe a Palestinian would have told him that they were trying to avenge the deaths of family members who died in an Israeli airstrike or that they wanted to liberate their country from an occupation. That wouldn’t have persuaded him that the Oct. 7 attacks were justified, of course, because they weren’t. The attacks would appear just as horrific even after an interview with an attacker. But it might have made it more difficult to conclude that these people were simply part of an evil death cult motivated by nothing beyond the desire to take life. The framing is the primary problem with the book. By keeping the focus almost exclusively on the crimes of Hamas and dwelling on Israeli victims while ignoring Palestinian victims, Murray is able to invert the reality of the conflict, turning the occupying power into the victim and the occupied into the aggressor. But Murray also commits serious crimes against basic intellectual integrity. Murray’s sourcing is sloppy (I noticed one paragraph clearly paraphrased from a New Yorker piece that he does not credit), and he simply cannot be trusted to be accurate. I do not make that claim lightly—Murray has previously sued a writer for libel for misquoting him—so let me provide proof of Murray’s inaccuracies. First: Murray says that when Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar was killed, proof was discovered that “one of [Sinwar’s bodyguards] worked as a teacher and was employed by UNRWA [the United Nations Relief and Works Agency].” This is false. The allegation stems from the fact that a U.N. teacher’s passport was found near Sinwar after his death. But as the Australian Associated Press explained, “the passport did not belong to Sinwar's bodyguard but to another man who is still alive.” UNRWA’s Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini publicly refuted the claim on October 18, 2024. He clarified that the man named in the passport, a Gazan UNRWA schoolteacher, “is alive… he currently lives in Egypt where he traveled with his family in April [2024] through the Rafah border.” He had fled Gaza months before and was nowhere near Sinwar at the time of his death. The man himself then confirmed that he was alive in Egypt and was not a Hamas bodyguard in Gaza. (See this France 24 report on the story.) To illustrate his argument that Hamas’s leaders have enriched themselves while depriving the people of Gaza, Murray claims that Sinwar’s wife “was even clutching a $32,000 luxury Birkin handbag” made by Hermès while hiding out in the tunnels beneath Gaza. In fact, this claim about the handbag, which originated with an IDF spokesperson, has also been debunked. A grainy video showed Samar Abu Zamar, Sinwar’s wife, holding a handbag, and some people online speculated that it was a Birkin, but there were obvious differences. Israeli businesswoman Nicole Reidman, who has been a brand ambassador for Hermès, said the bag was “trash” and clearly not a Birkin. There are other misstatements. Murray says, for instance, that the Palestinian Authority has insisted that “no Palestinian state could have Jews in it” and “the one absolutely clear precondition for such a state was that no Jews could exist within its borders.” Murray does not cite a source for this claim, which turns out to be the opposite of the truth, as you can read even in a Times of Israel article entitled “Palestinians: Yes to Jews, no to settlers in our state.” Palestinians have said that they do not want in their state Israeli settlers, those who seize territory that they operate by their own laws. But the Palestinian Authority has said that this does not mean “no Jews allowed.” Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad said in 2009: “The kind of state that we want to have, that we aspire to have, is one that would definitely espouse high values of tolerance, co-existence, mutual respect and deference to all cultures, religions. No discrimination whatsoever, on any basis whatsoever. […] Jews to the extent they choose to stay and live in the state of Palestine will enjoy those rights and certainly will not enjoy any less rights than Israeli Arabs enjoy now in the State of Israel." Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat has said "I hope the day will come when Israelis can live freely in the state of Palestine." “If Netanyahu argues that these positions are against Jews, we say to him that two Jews were elected in 2009 as members of Fatah’s Revolutionary Council: Ilan Halevi and Uri Davis,” Erekat said. “Our position is against settlements, considering them illegal and contrary to all international laws.” Hanan Ashrawi of the PLO’s executive committee said: “Any person, be he Jewish, Christian or Buddhist, will have the right to apply for Palestinian citizenship. […] Our basic law prohibits discrimination based on race or ethnicity.” Indeed, the Palestinian Declaration of Independence in 1988 had explicitly forbidden discrimination “on grounds of race, religion or colour.” How, then, is it a “clear” precondition for a Palestinian state that Jews would be banned from it? Murray is just factually incorrect here. Or consider a statement like this: “Conditions in Israeli prisons used to be fairly relaxed for Palestinians. Palestinians I have spoken with who were in Israel’s jails before the 7th related how they had semi-open-air markets where they could buy and eat chicken shawarma and other dishes.” (160) In fact, Israel was infamous for cutting off prisoners from contact with their families, torturing them, sexually abusing them, and holding them in “conditions that violate international humanitarian and human rights conventions” including by placing children in solitary confinement. Palestinian prisoners repeatedly went on hunger strikes to protest their conditions. Of Mahmoud Khalil, Murray has said in a March 2025 video: “You might wonder what a 30-year-old is doing at Columbia University, and I’ve been wondering that a bit. It turns out, by the way, that this guy who was organizing these protests and leading them lived in Columbia University student accommodation but was not actually a student. That’s an odd thing in itself.” In fact, there is nothing “odd” here. Murray is just wrong. Khalil was a student; he was due to graduate in May of this year. He’d finished his coursework in December, but he was still in his housing because the university lets students stay in their housing through graduation. As for why Khalil was 30, it’s because he was in graduate school, and the average age of a graduate student in the U.S. is 33. Murray is clearly grasping at anything he can to try to impugn Khalil. Murray also has clearly not rigorously investigated the sources for his quotes. To bolster his claim that Hamas is a “death cult,” he cites a purported quote from Ismail Haniyeh: “Children are tools to be used against Israel. We will sacrifice them for the political support of the world.” What’s the source for this quote? Well, turning to Murray’s endnotes, we find it cited to atweet from an anonymous account called @EretzIsrael. The tweet provides no source for the quote. It contains a date, Jan. 17, 2017, but I can find no evidence that Haniyeh said it. Now, a proud Oxford man like Murray should know that even a freshman college student would not get away with citing a random anonymous tweet as a source in a bibliography. He does only slightly better in supporting his claim that Hamas’s leaders are billionaires, citing the tabloid newspaper the New York Post, which itself provides no evidence except an assertion by the Israeli government. (The claim that Ismail Haniyeh, Musa Abu Marzouk, and Khaled Masal, are/were personally worth billions is widespread across the internet, but I can find no clear, verifiable evidence for the claim, despite fabricatedForbes coverspromoted by the Israeli Foreign Ministry.) Murray has even made claims that appear to be entirely unsourced. For instance, on the Joe Rogan appearance, Murray explained away the scale of the physical destruction in Gaza. For context, recall that over 70 percent of Gaza’s housing stock was damaged or destroyed by early 2024 (Israel is now planning to flatten all of the buildings that remain standing), with “one of history’s heaviest conventional bombing campaigns” inflicting destruction comparable to the bombing of Dresden. This was Murray’s justification for the destruction: “One of the reasons why the destruction looks so bad and is so bad is because when the IDF were clearing the areas that they'd asked the civilian population to leave and were going house to house, and it isn't just stories here or stories there, it's every second or third house in Gaza that has either munitions or tunnel entrances. Every second or third house. It is not the odd case. […] Why is this so normal that every civilian building like this and every second or third house in Gaza is a weapons dump or a place that you enter the tunnels from?” Surely “every second or third house” must be hyperbole. But Murray says it three times, and appears to mean it. What evidence is there to support this? IDF members have made similar claims, but as for evidence, I can’t see any. (Murray does not include the claim in the book.) Oftentimes, Murray writes his descriptions of events in ways that leave a misleading impression about them. For instance, in his section on how Iran became “one of the biggest imperial powers of the age,” he says that after the Iranian revolution in 1979, the Islamic regime “spent its decades in power taking over not just Iran but the wider Middle East.” Murray’s next sentence is “In the 1980s it fought a bloody war against Saddam Hussin’s Iraq, which killed half a million people.” From this, you would think that Iran tried to take over Iraq. But the opposite is true: the Iran-Iraq war was waged by Saddam Hussein, who illegally invaded Iran. Hussein was ruthless in his use of chemical weapons and was supported in his aggression by the United States. Murray, of course, does not mention this, because he wants to leave the impression that Iran is a purely aggressive country, and the idea of it acting defensively is at odds with that picture. Naturally, while he says the regime came to power with “the overthrow of the Shah’s government,” he also does not mention that the Shah was one of the region’s most brutal dictators, or that he had been installed in a U.S.-backed coup in 1953 and continuously propped up with U.S. military aid. These facts might convince you that the world is complicated, and not divided into “democracies and death cults,” and so they must not be mentioned. (Murray also says Gaza is a “colony of Iran,” an outlandish claim that appears to be based on Hamas receiving military support from Iran. This reasoning would make Israel a “colony of the United States.”) Every time Murray makes a claim, it is wise to look it up, because you will discover how he is carefully misleading you. Consider the sentence: “One speaker used the platform of Columbia’s protest movement to promise more massacres [like October 7].” Now I would assume from this Murray was talking about a speaker at an event, not just a random person who showed up and shouted something. But turning to the video evidence Murray cites, it appears that someone did shout this at pro-Israel protesters, but it was a random masked man shouting outside Columbia, not a “speaker” using any kind of platform. Or consider his account of Hamas’s seizure of power in Gaza: “In 2006, under pressure from the United States administration of George W. Bush, among others, the PA were pushed into holding legislative elections in Gaza. The Iranian-backed forces of Hamas beat [rival political organization] Fatah convincingly, and in the aftermath Hamas solidified its grip on power by murdering Fatah officials in Gaza. Scores of Palestinians were executed in the streets, thrown off tall buildings, shot in the back, and in some cases had their bodies dragged through the streets of Gaza, tied by rope to the backs of motorbikes driven by exultant Hamas militants. From that day on, there has not been another election in Gaza…” Missing from this account: when Hamas won the elections (which were in all of Palestine, not just Gaza), instead of respecting the results of a democratic election, the United States and Israel immediately imposed sanctions and supported efforts to isolate and undermine the new government. Fatah tried to maintain control in spite of the election result to keep Hamas from governing. A power struggle ensued in which both sides committed serious crimes. The U.S. encouraged Fatah to stage a coup against the Hamas government, and Hamas seized control of Gaza to preempt the coup. These details matter, because in Murray’s account, Hamas is simply a death cult committed to murder. (Likewise, Murray says nothing about the Great March of Return, a peaceful demonstration by Palestinians which was met with Israeli bullets and which was important in convincing many Palestinians that nonviolent resistance was simply suicidal.) In fact, the chief problem with the book throughout is that it is missing information. Murray does tell us that Israel is a “pluralistic, multiracial, and multicultural society.” He does not tell us that Israel’s own prime minister says “Israel is not a state of all its citizens… [but rather] the nation-state of the Jewish people and only [them].” He does tell us that “Operation Cast Lead in [2008] was explicitly launched by Israel in order to stop the firing of rockets from Gaza into Israel,” but he does not tell us that Israel was the party who actually broke the ceasefire that was then in place. He does tell us that the IDF are morally superior to their enemies in part because while Hamas revels in atrocities, Israel only commits them reluctantly, and “of all the soldiers I saw in war, none took delight in their task.” He does not tell us about the mountain of video evidence showing IDF soldiers gleefully celebrating the destruction of Gaza with just as much relish as the attackers on October 7 had. He says that when Israel withdrew its settlers from Gaza in 2005, Gaza “could have been a thriving Palestinian state.” He does not disclose that an adviser to the Israeli prime minister explained that the very purpose of the withdrawal was to “prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state.” He does tell us that Hamas, in their death-worshiping depravity, attacked an ambulance on October 7. “No one but Hamas” would “fire on an ambulance,” he quotes an Israeli saying. Well, what Murray does not tell us is that Israel itself has fired on a number of marked ambulances. (The latest attack, in which Israel killed 15 medics, crushed their ambulances, and then lied about the incident, occurred after Murray’s book was written.) Murray briefly mentions the level of destruction he saw in Rafah (where he did a photoshoot at the site of Sinwar’s death), which was so obvious that even he could not overlook it. Every building was “covered in rubble when not reduced to it altogether,” he writes. But this does not make him curious about the stories of the Palestinians who were buried under the rubble. For Murray, they started the war, so whatever happens is their own fault. Murray’s empathy is totally lopsided. Despite his moving profile of the pathologists in Israeli morgues, Murray does not seem to wonder about the morgues in Gaza, where, you will not be surprised to learn, the conditions are horrendousand many bodies simply cannot be identified, leaving families with no answers as to whether their relatives are alive or dead: Israel [...] has imposed a crippling blockade that has starved Gaza of medical supplies, including the tools necessary to perform genetic identification. Inside the morgue in Gaza City, forensic doctor Imad Shehadeh works silently in what he describes as catastrophic conditions, examining body parts and decomposing remains with only basic tools. The smell of death mixes with smoke and dust, the room crowded with human remains - some reduced to bare bones. "We're overwhelmed by the growing number of decomposed, unidentifiable bodies," Shehadeh told Anadolu Arabic. "We don't have DNA testing equipment, and Israel has blocked all efforts to bring any in. Without it, it’s almost impossible to identify most of these people." In a recent conversation with Bari Weiss, Murray reiterated his view that media outlets should broadcast the views of people who are intellectually serious and have some expertise. The fact that the media is often insufficiently skeptical, he said, “does not mean that absolutely everybody should be given the platform to spread untrue things.” But if this is so, it raises the question: Why is Douglas Murray himself given a platform to spread untrue things? Instead of discussing the question “Who is an expert?” we should always ask a different set of questions, namely: “What is the argument being made and what is the evidence provided in support of it?” It doesn’t matter who has been to Israel, it matters what the proof for their claims is. (After all, both Murray and Ta-Nehisi Coates have been there, but they reached very different conclusions.) The focus should be on Murray’s thesis and the support he provides for it. Plenty else is irrelevant: the fact that he’s spent time in the region, the fact that he has a posh British accent, the fact that his book is a bestseller, the fact that the Times of Israel calls it important. We must zero in on what Murray is arguing and whether it happens to be true. When we do, we quickly see that his argument is nonsense and filled with deception. * Note that while Murray often speaks of the crimes of Hamas, he treats Gazans as a radicalized population who “seem, as far as we can tell, to approve of the motives of [Hamas] and its ambitions. If there are any moderate Gazans out there, this would be a great time to speak up.” ** Interestingly, Murray says that “The State of Israel has equal rights for everyone in the country.” This obfuscates the situation. Jews in America are allowed to move to Israel but Palestinian refugees from what is now Israel are not. In practice this means that a Jewish citizen of Israel is entitled to bring their Jewish family members to live with them from abroad, but an Arab Israeli is not. But another crucial question is what Murray means by “the country.” After all, this is plainly not true if the “country” includes the West Bank, where Palestinians are governed by Israeli military law rather than civil law, cannot vote, face hundreds of checkpoints, are barred from certain roads, are arbitrarily detained, and have their houses demolished. Does Murray think “the country” includes the West Bank? It seems he probably does, because he opposes a Palestinian state and refers to the Occupied Territories as “Judea and Samaria,” the term used by those who think of them as part of Israel. Only if you think of the West Bank as not being part of Israel can you claim Israel has “equal rights for everyone.”

“If you’re going to talk endlessly about a conflict, you ought to do what I do, and at least put in the legwork.”

Douglas Murray

Current Affairs

Tuesday 6.5.2025