Essay by Geoffrey Rathgeb Aung, written for Endnotes and Chuǎng.1

Do not all uprisings, without exception, have their roots in the wretched isolation of men from the community (Gemeinwesen)? Does not every uprising necessarily presuppose isolation? Would the revolution of 1789 have occurred without the wretched isolation of the French citizens from the community? It was intended precisely to abolish this isolation.

— Marx,

“Critical Notes on the Article: ‘The King of Prussia and Social Reform. By a Prussian’”,

Vorwarts! No. 63 August 1844 (MECW 3): 204-205, translation adapted.

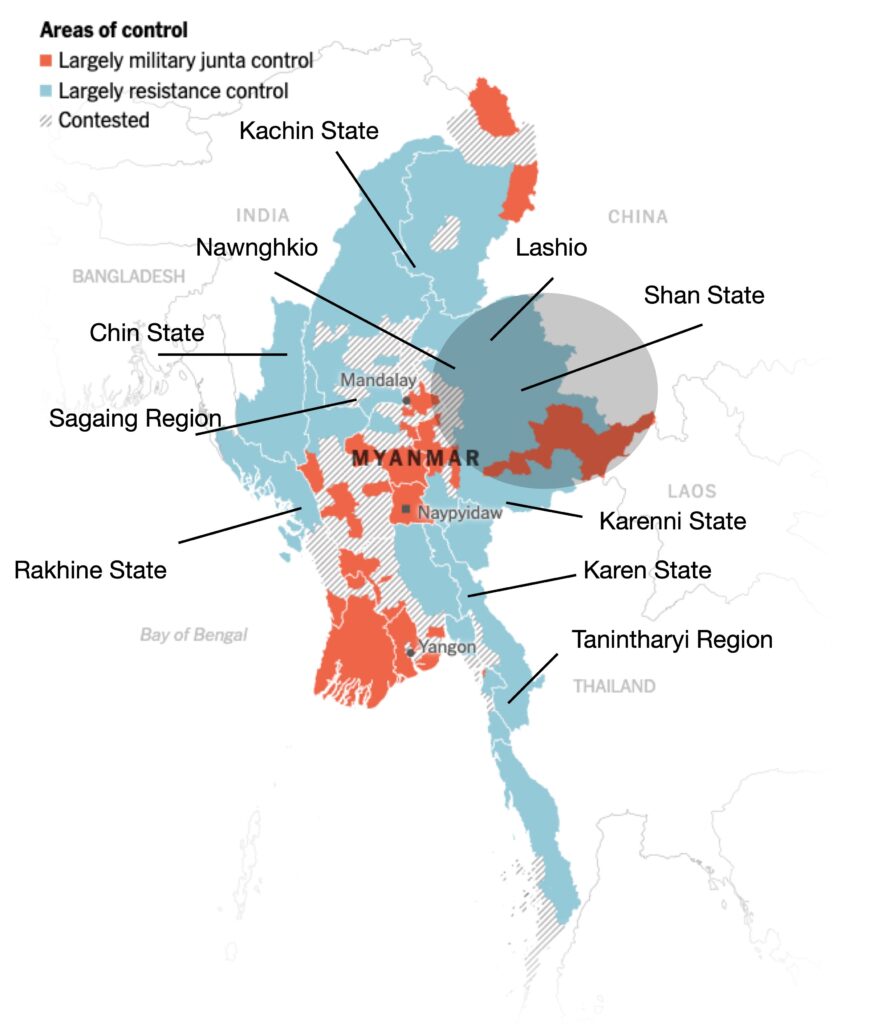

Another town in Myanmar fell to armed resistance forces this past summer. In July, a joint operation carried out by the Mandalay People’s Defense Force and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA)2 captured Nawnghkio from the Myanmar military. By seizing the town, they gained a weapons cache, including an anti-aircraft missile system. Nawnghkio is also on the road from Mandalay through Lashio to China—Myanmar’s most important trade route. The resistance had now severed this route. They thereby dealt an economic blow to the junta while potentially forcing China to negotiate a reopening of the route on terms favorable to the resistance. A former army major, a prominent defector, summarized the operation. “By capturing Nawnghkio,” he said, “the resistance forces can now control the Mandalay-Lashio road.” The road is logistically strategic, too: the military used it to supply the frontlines in northern Shan State with troops and ammunition.

A new dawn beckons—or such is the promise of the last year. Resistance forces made striking territorial gains well beyond Nawnghkio, across Myanmar’s northeast, north, and west. Bold assaults on Naypyidaw, the capital, and Myawaddy, a crucial Thai border crossing, left the military junta looking remarkably fragile. Resistance fighters seized two regional military commands, in Shan State and Rakhine State. In liberated areas, autonomous administrations are delivering health, education, and other services, securing survival against the regime’s onslaught. In the largest city, Yangon—where my family is just trying to survive soaring inflation and not get arrested—clandestine resistance cells still operate, staging flash mobs and banner drops while funneling recruits to armed groups.

Still, the end of the military regime appears little nearer than a year ago. Much of the lowlands remain under military control, especially around Yangon and the Ayeyarwaddy delta. Despite disaffection and desertion in its ranks, the junta’s advantage in artillery and airpower means it can ravage liberated areas (they pounded Nawnghkio with some 100 airstrikes after losing the town). Late last year, the regime also launched counter-offensives in Myanmar’s east and northeast—albeit with little success thus far—while renewed Chinese support has helped the junta restabilize itself. Meanwhile, a newly implemented conscription law sparked panic. The law signals desperation, not strength, on the part of the military. But as the military holds onto power, worries abound that the most difficult, most dangerous, phase could be yet to come.

The road to Nawnghkio: coup, blockade, rebellion

How did we get here? Nawnghkio is not itself a turning point or a game-changer, but it is one of dozens of strategic locations seized by resistance fighters since late 2023. The victory reinforced the dominant trend of the last two years: advancing resistance control reflecting mounting junta losses. A crescent held by the resistance now stretches across much of Myanmar. The arc begins at the eastern border with China in Shan State; it runs through Kachin State in the north, and then Sagaing Region and Chin State towards the west; and it extends south to Rakhine State on the Bay of Bengal. Along the eastern border with Thailand in Karenni and Karen States, additional clusters of resistance control nearly connect with territory held by resistance fighters farther south in Tanintharyi. While the junta still controls the southern lowlands, groups like the Mandalay People’s Defense Force and the TNLA have secured major territorial gains not only in the highlands, but also around cities in the upper lowlands like Sagaing and Mandalay. As the regime seeks to reconsolidate and regain lost territory in Shan, Karenni, and Karen States, resistance forces aim to hold that ground and encircle Mandalay, Myanmar’s former royal capital. Naypyidaw, on the horizon, is only 190 km south.

The shape of this conjuncture—its morphology, its territorial imprint, and its composition, reflecting a bewildering variety of actors—owes much to the sequence of insurrection that followed the 2021 coup, which in turn ended a decade of liberal reforms. This sequence will help illuminate the fulcrums and lineaments, the tensions and contradictions, that define this moment. Today, smashing the regime remains a distinct possibility, even as the military restabilizes. That is at the core of a story that holds great appeal, in which a courageous armed resistance unites to defeat the military and build a peaceful, federal democracy. But that story translates poorly on the ground. No single revolutionary subject is at hand to guide, direct, or prescript this open insurrectionary sequence in one direction or another. Instead, contradictions within Myanmar’s sprawling armed resistance leave little clarity about what kind of sovereign order might emerge, or even whose vision provides for genuine revolutionary promise. Still, this is less cause for despair than a sign of historical conditions, which offer a better guide to insurrectionary ruptures than any singular heroic subject. To paraphrase Brecht’s Galileo—unhappy is the land that needs heroes in the first place.

Coup

The coup of 2021 came as something of a surprise. In the 2010s, the military oversaw a careful shift from outright military rule to formal civilian government, while conserving considerable political and economic power for itself. In 2011, the military appointed Thein Sein, a former general, president. After the 2015 elections, the long-outlawed opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), took power. The NLD’s leader, liberal icon Aung San Suu Kyi, is the daughter of Aung San, the independence hero who founded the Myanmar military in resistance to British rule. Suu Kyi has always stated her fondness for the military, given its historical ties to her father, despite being seen as the military’s defining modern adversary. Under NLD rule, the military reserved a quarter of seats for itself in parliament. Key ministries remained under military control: defense, home affairs, and border affairs. The military’s economic stature had also grown considerably since the 1990s, when market liberalization found generals, their cronies, and military holding companies securing dominant positions in a growing private sector. By 2015, the generals’ expansive economic control meant formal political control mattered less than it would have otherwise. Liberal democracy only further enriched the generals as Western companies began to invest, particularly in resource extraction and the garment sector. At the same time, movements of workers, peasants, and students contested this period’s top-down electoralism and intensified export-oriented extractivism.

Relations between the NLD and the military appeared mutually beneficial. But a closer look might have revealed cracks in this bloc by the late 2010s. Foreign investment spiked in response to thorough market deregulation in the early and mid-2010s. By 2017, however, halting growth rates coincided with an upsurge of conflict in Kachin and Shan States, as well as the military’s ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, which made for reduced Western investment. And although Suu Kyi infamously defended the Myanmar government against charges of genocide at the Hague in 2019, she pushed for constitutional amendments that would have helped extract the military from politics (getting rid of, for instance, their seats in parliament). With conflict resurgent, investment falling, and renewed tension between Suu Kyi and the military, the 2020 elections came at a sensitive time. As in 2015, the NLD won overwhelmingly. But now, the military alleged “terrible fraud in the voter list”—a claim of widespread irregularities denied by the election commission and international observers. Weeks later, and only hours before the new parliament was set to meet for the first time, the military seized power. On the morning of 1 February, 2021, they detained Suu Kyi, other top NLD officials, as well as artists, dissidents, and journalists who were seen as potential threats. On their television network, the military declared a state of emergency during which Senior General Min Aung Hlaing—its commander-in-chief—would rule.

In the hours and days that followed, phone and internet service cut out. Shops locked up; banks, buses, and airports shut down. Critics of the military went underground. Friends and family described a charged atmosphere. Everything felt taut, strained, on edge—chilling, if also resonant with possibility. Yangon echoed at night with discontent. Residents banged pots and pans, while drivers honked their horns—a cacophony to drive off evil spirits. In Mandalay, medical workers organized early. Gathering in groups, masked faces lit by their phones, they sang the anthem of the 1988 uprising: Kabar Makyay Bu. The title is a call for struggle against military rule—“until the end of the world.” Doctors, nurses, and civil servants called for work stoppages and mass disobedience; workers and students put out calls to take the streets. A friend in Yangon said they were on the run but safe—although others had been arrested. In the south, another friend got in touch: “We will fight back as much as we can.”

Blockade

Over the next few days, demonstrations began to take shape. Despite a ban on gatherings of over five people, crowds swelled into the hundreds and thousands—often at centrally located squares and intersections. From the big urban centers like Yangon and Mandalay to smaller cities like Dawei, Monywa, and Myitkyina, people staged marches and blocked roads. In more rural areas, village strike committees held smaller demonstrations, while roving motorbike columns drummed up support. Factory workers—mainly women from rural areas—were pivotal. They organized, went on strike, and led mass demonstrations in Yangon before even a week had gone by, building a strike wave that spread across other sectors. Insurrection rippled across the country. At the largest demonstrations—ultimately featuring hundreds of thousands of people in Yangon alone—a celebratory mood emerged. Music and dancing, costumes and food, and impromptu speeches made for an atmosphere at once festive and defiant. A picture came in from Dawei, in the south. Across a sea of people, I could see a friend—mic in hand and raising a fist—energizing the crowd as thousands gathered in the town center.

Mass demonstrations paralyzed traffic. In Yangon, “broken-down car protests” saw protesters leave old cars in strategic locations to stop the movement of military and police vehicles. In the northeast, protesters in Shan State blockaded the main trade route to China—briefly, but in a way that foreshadowed the capture of Nawnghkio three years later. Rumors circulated of attacks on the pipelines moving oil and gas to China and Thailand. The rumors proved false—until now, still no pipeline attacks have been confirmed—but they signaled the kind of insurgent imaginary at work. Myanmar’s ports, meanwhile, became nearly inoperable. Striking truck drivers, customs agents, port workers, civil servants, and bank staff brought international trade through Myanmar’s ports nearly to a standstill. They drove down exports as much as 90% in the weeks following the coup. Imports fell by around 80%. A kind of common sense prevailed: the motion, movement, and rhythms of everyday life—from work, to traffic, and trade—had to be brought to a halt.

The shift from this initial post-coup insurrection—organized around demonstrations, blockades, and occupations of urban spaces and trade hubs mainly in the central lowlands—to a largely rural armed struggle—grounded in the Burman upcountry and the minoritized ethnic highlands—did not come about easily. In Yangon and Mandalay, cops and soldiers started raiding neighborhoods at night, carrying off suspected protest leaders to black-site detention centers from which some never returned. Security forces, formerly content to stand by as demonstrations grew, began using live rounds for crowd control. The number of protesters killed slowly climbed. The military gradually regained control of major urban areas. I found myself swapping crowdsourced images with my cousins in Yangon. The images originated from comrades in Hong Kong, showing what “frontliners” came to learn well: how to build barricades, extinguish tear gas, wash out eyes, and tend to gunshot wounds.

As junta violence escalated, the insurrection became more militant. Its composition, geography, and tactics changed. As cops and soldiers used deadly force to reclaim central squares and intersections in Yangon and Mandalay, the working-class urban peripheries became key sites of more antagonistic confrontation. Gone were the music, dancing, and festive atmosphere of the early mass demonstrations, in which wealthier protesters living in these richer areas had taken part more easily. In those earlier stages, a roughly middle-class composition had tended to dominate, notwithstanding factory workers’ crucial role in catalyzing the demonstrations. This had brought with it a certain attachment to the reform period’s promises of economic and political liberalization, since abrogated by the coup. The initial imaginary of the rebellion took as its horizon the restoration of liberal norms. The new phase pointed beyond this horizon. Places like Hlaingtharyar and Myauk Okkalapa now loomed large—the so-called hsin-kyay-boun, or elephant’s feet: industrial zones on the outskirts of Yangon that serve as sprawling catchment areas for the poor, the lumpen, the dispossessed.

In mid-March 2021, six weeks after the coup, cops moved in to clear a series of barricades erected in Hlaingtharyar. Witnesses recounted remarkable scenes: unarmed factory workers, carrying improvised shields, surged over flaming barricades, charging police lines in waves as live bullets pierced the air. Some fifty people died—a far higher death toll than anything seen so far in the more central neighborhoods. But the roads in Hlaingtharyar are not easy to blockade. Open, and wide, built for factories that depend on trucks moving in and out to the nearby port, they were harder to fortify than the denser neighborhoods of Myauk Okkalapa. As barricades sprang up in Myauk Okkalapa, bloodshed followed. Cops and soldiers killed a hundred people in one day at the end of March. Still, frontliners could defend areas like this more resolutely. In the narrower streets here and in Myauk Dagon, for instance, and even back towards more central areas where protestors sought to reclaim and fortify some neighborhoods, frontliners decked out in gas masks, helmets, and shields organized disciplined formations. Shield-bearers defended the barricades at the front; another group smothering tear gas came behind them; and at the back, a third group helped maintain the formation and its momentum. This third group also roped in onlookers and sympathizers while scanning for cops at the rear. In some places, frontliners battled security forces to a standstill, creating tense and draining cycles of confrontation that, to be sure, were difficult to maintain over time.

Rebellion

The urban insurrection proved unsustainable. Grounded in a shifting and heterogeneous composition of workers, civil servants, and youth, the urban insurrection was remarkably disciplined for a largely organic, self-organized revolt. However, its characteristic forms—the occupation and the blockade, from the city center to neighborhood self-defense at the city’s edges—proved too challenging to reproduce against the overwhelming force of the state. At the same time, the failure of this insurrectionary sequence should not be taken at face value. It opened onto and shaped the much wider rebellion that has followed.

The regime’s bloody pacification of towns and cities pushed rural areas decisively into view. Repression extended unevenly into areas outside the cities; in some areas it was absent. Though they had hardly been inactive before, rural areas soon became crucial to sustaining mass resistance. In Dawei, for instance, security forces reclaimed the town center in April, having killed a dozen or so protesters. But as the town fell under military occupation, the villages nearby saw a surge in marches, demonstrations, and strike activity, including those mobile motorbike columns. Urban rebels—as it now makes sense to call them—also began fleeing to the rural highlands controlled by ethnic resistance organizations (EROs, in current parlance), such as the Karen National Union (KNU). Like other EROs in Myanmar’s east, northeast, north, and west, the KNU’s armed rebellion against the lowland state stretches back to the earliest years of independence from British rule. Now, the rebels from urban areas joined them, and many began to receive guerrilla training. They learned how to use firearms and grenades; they learned about tactical strikes on military installations and troop convoys. They learned what it takes to seize, defend, and administer territory. Some of the new rebels were absorbed into EROs like the KNU. Others formed their own armed resistance groups. As they proliferated, these resistance groups came to be known as PDFs: People’s Defense Forces.

This was the road to Nawnghkio. The urban insurrection was not able to topple the new regime in the center. Instead, rebels in and from the Burman lowlands took up arms in rural areas, in some cases fighting alongside long-standing EROs—like the Mandalay PDF’s joint operation with the TNLA to capture Nawnghkio. The rugged highlands of Myanmar’s current rebel crescent—that half-moon of territory now largely controlled by armed resistance forces from the northeast across the north to the west and along the Bay of Bengal—are all areas where the Burman state-making project has struggled to project power, even since independence. Rebel activities have flourished in these areas for generations. But they are not areas where armed rebellion has recently tied into and linked up with resistance activities in the Burman lowlands—in part because the Burman center has not for some time thrown itself into armed rebellion, not since the peasant wars of national liberation in the 1930s and 40s and the communist insurgency that emerged thereafter through the 1960s. The revolt after the 1988 uprising saw some of these dynamics; urban protesters fled to areas controlled by EROs. But the Burman heartlands remained firmly under military control. Today, though the military retains control of the southern lowlands around Yangon, the Burman upcountry around Mandalay and Sagaing is a crucible of armed rebellion—and increasingly integrated with ERO operations based in the highlands. From late 2023 into most of 2024, the territorial gains in places like Nawnghkio raised the possibility of a battlefield victory over the Myanmar military—even if major challenges reasserted themselves by late 2024.

The road from Nawnghkio: insurgency, autonomy, empire

Insurrections come and go. From the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s—an insurrectionary cycle touched off as much by deadly police violence as by capitalist crisis—revolts rippled from urban outskirts to city centers across sites as disparate as the French banlieue, London’s Tottenham Hale, and the central squares of north Africa, Turkey, Greece, Spain, New York, and California. Tahrir remains the essential emblem of that historical cycle, the “pulsing center” so necessary to that moment. Squares, plazas, neighborhoods, parks, occupations, and blockades constitute the tactical syntax of this period. But generalizing and extending these ruptures became nearly impossible. In Europe and the US, revolts struggled to move beyond the square and the plaza. Occupiers failed to take or hold buildings and labor alliances fell apart, while party vehicles proved more coda than catalyst for the mass movements they claimed—from Syriza to Podemos, Corbyn to Sanders. In the Arab world, Egypt’s sequence revolt-election-coup came to stand next to the conflagrations of Syria and Libya as signal references for popular uprisings undone, even if the Syrian sequence has taken another important turn.

A second wave of this cycle beginning in the late 2010s—including the struggle in Chile, Hong Kong, the George Floyd rebellion, Thailand’s anti-monarchy revolt, the Gilets Jaunes, strike waves in Vietnam and Indonesia, the Wet’suwet’en Nation, Ecuador, Stop Cop City, Lebanon, Standing Rock, Iraq, Iran, and the student intifada within the broader Palestine solidarity movement, to name but a hastily assembled few—leaves no shortage of open questions. But problems of extension and generalization continue to loom large, even if the emblem of the square has, arguably, tended to give way to a logistical injunction: block everything. The blockade remains at the center of the insurrectionary arsenal.

In the wake of these cycles, and against the backdrop of a long transition from US hegemony to multipolar, systemic turbulence, Myanmar’s insurrectionary sequence stands out. Rebels have managed to extend and generalize an insurrectionary rupture beyond the initial occupation of urban centers, which the military reclaimed through deadly force. Rather than dissipating into party vehicles—not possible after the coup—or destruction by warfare between rivals, as in Libya and (until recently) Syria, the insurrection in Myanmar has achieved a transition from occupied squares to armed struggle. In so doing, the rebels have fused together the signature forms of this century’s insurrections with last century’s national liberation struggles, including the lexicon of people’s war (in Myanmar today: a “people’s defensive war”). This fusion is incredibly fragile, however. It is vulnerable in particular to a contradiction between insurgency and autonomy in this ongoing sequence of revolt—from Nawnghkio looking forward.

Myanmar’s insurrection condenses the sequence of revolts elsewhere in this century. […] As Myanmar’s insurrectionary rupture climbed hills to ignite a rural armed struggle, however, a new set of contradictions emerged. This is where the principle contradiction between insurgency and autonomy enters.

Insurgency

Myanmar’s insurrectionary transformation—its overcoming, so far, of key blockages that have marred the ruptures and revolts of this century—is not entirely surprising. First, the shift to armed struggle reflects the long-standing strength of EROs in Myanmar’s highlands, some of which had signed ceasefire agreements during the reform period, and some of which had not. Myanmar’s particularity, it could be argued, is that urban rebels could flee to the hills and find a landscape of heavily armed insurgent groups—already active for several generations—ready and able to cooperate in expanding and reproducing an insurrectionary rupture—even if tensions between urban rebels and rural EROs have been far from unknown in the jungle camps of the hills.

Second, a shadow government formed by MPs elected in 2020 has emerged to provide some degree of leadership to an otherwise decentralized resistance movement. This National Unity Government (NUG) is active in some liberated areas, but its stronger presence is in exile in Thailand and the West, including Washington DC and several European capitals. The NUG is a political and diplomatic mechanism much more than a military force. Still, it has arguably been productive for a sprawling landscape of PDFs to fight not under NUG control, but under the various ERO chains of command, between which the NUG has been able to offer some joint coordination mechanisms. It is the EROs, no doubt, that have the necessary guerrilla expertise.

Third, and relatedly: a motley insurrectionary composition has largely held together. In the Myanmar left, like everywhere, there is debate about who, if anyone, is capable or deserving of leading a revolutionary movement in the absence of a large, organized, and self-conscious working class. After the pacification of urban centers in the first months following the coup, it appeared clear enough that no single revolutionary subject—certainly not one based in the small industrial working class, however crucial the latter was to sparking mass demonstrations in Yangon—had the power to defeat the new regime. This pointed toward a more heterogeneous composition. The armed struggle, forged across lines of spatial (urban/rural, lowland/highland) and ethnic difference, represented an attempt at a cross-class revolutionary front. It made for a sundry mix of Burman MPs elected in 2020, battled-hardened ERO brigades, urban youth-cum-jungle rebels, and a peasant social base that historically produced durable guerrilla struggles across Myanmar’s lowlands and highlands. Although there is no question that the rebel highlands made Myanmar’s insurrectionary transformation possible, even the Burman lowlands have a long history of armed revolts against centralized state-making projects, not least given how feebly state projects have projected power beyond their centers. While ethnic rebellions have deep roots in Myanmar, a decades-long communist insurgency engulfed the Burman lowlands before also shifting into the hills in the middle of last century. It drew on and reworked the repertoire of armed rebellion that anti-colonial nationalists had taken over from a much longer history of millenarian peasant revolts—the Saya San rebellion of the 1930s having proved the epochal hinge between eras.

Still, earlier revolts and uprisings against post-independence military rule did not durably transform into generalized armed struggle—this despite the existence of armed ethnic insurgents that might have joined with Burman rebels in 1976, 1988, 1996, or 2007, for example. Those uprisings did not climb hills, as it were, nor activate the lowlands’ history of rebellion. The outstanding difference today is arguably the reform period that preceded it. For some of today’s rebels, the intensity of armed resistance reflects an attachment to the promises of those reforms, undone so suddenly and all too soon. To an extent, they are fighting to regain those fleeting glimpses of liberal democracy and capitalist development while finallyabolishing military rule. Many others whose place in society already excluded them from the spoils of liberal reform in Myanmar did not experience the reform period as it was presented—in the political idiom of a promise. For those whose position left them at best ambivalent, the reform period may have meant little at all: the poor and working classes of the fields and the factories; students who mobilized for more radical democracy during the reform period; the highland peasantries who maintained armed rebellions against the Burman state during the reform period; and the Rohingya in Rakhine State, whose ethnic cleansing during the reform period appeared to many as a shocking contradiction (it was not). A final confrontation with military rule, however, is not simply an empty promise.

In effect, Myanmar’s insurrection condenses the sequence of revolts elsewhere in this century. It begins with the relatively mild occupation of public squares. As cops and soldiers move in and bullets fly, the revolt intensifies and becomes more militant, more openly insurrectionary. Its center of gravity shifts from wealthier urban centers to proletarian urban peripheries, where barricades form and frontliners emerge. At this point, the sequence breaks down. All of the learning, borrowing, and tactical emulation that has happened within and across revolts meets a kind of limit as the earlier stages exhaust themselves. What comes next? This is one way of thinking about the value and significance of the insurrection in Myanmar. Its contribution to the revolutionary toolset of the coming decades—decades set to be defined by interlocking economic, political, ecological, and epidemiological crises—lies in the answers that have emerged at that limit point. Its contribution, in fact, lies in the renewal and remaking of peasant insurgency as revolutionary struggle—precisely in the notion of people’s war. As Myanmar’s insurrectionary rupture climbed hills to ignite a rural armed struggle, however, a new set of contradictions emerged. This is where the principle contradiction between insurgency and autonomy enters.

In 2021, the regime reclaimed urban centers within months, leading to a reconsolidation of resistance around armed struggle in rural areas. And in late 2021, as the rainy season came to an end (the dry season is historically the fighting season in Myanmar) the acting president of the NUG announced a “people’s defensive war.” He called for “a nationwide uprising in every village, town, and city, in the entire country at the same time. We will remove Min Aung Hlaing and uproot dictatorship from Myanmar for good—and be able to establish a peaceful federal union that fully safeguards the equality that is long-aspired to by all the citizens.” At that time, People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) were proliferating organically. Military analysts and media reports echoed Maoist terms in speaking of a first stage of revolutionary war: a stage of “strategic defense,” when it would be enough for resistance fighters simply to survive initial assaults by the regime. It would be followed by a second stage of “strategic balance,” when resistance groups would develop larger and more mobile units, better equipped and better coordinated. Only in the third stage would “revolutionary forces,” now understood as such, fully seize the offensive. By that point—after several years or so—they would be using regular or semi-regular forces that, increasingly, would confine regime forces to urban areas.

Remarkably, the armed struggle in Myanmar has largely followed that trajectory. From late 2021 to late 2022, urban rebels trained with established EROs. Within the loose framework of people’s defensive war, PDFs sprang up, consolidated, and built ties with other armed groups while defending themselves against an initial onslaught by regime forces. PDFs also staged their own attacks on troop convoys and military infrastructure as they moved forward with operations within EROs, often under their chains of command, or more independently, while affiliating more or less closely with the NUG. The NUG, meanwhile, founded a Ministry of Defence to coordinate among PDF activities and between PDFs and EROs. That period of forming and consolidating armed resistance groups already saw heavy fighting with regime forces not only across the highland arc that forms today’s rebel crescent, but also in the Mandalay-Sagaing area of the upcountry lowlands where Burman PDFs have proven especially capable. By late 2022, it was already possible to speak of territorial control and consolidation by resistance forces that, in forming liberated areas, were starting to limit the regime’s outright control to lower Myanmar in Yangon and the Ayeyarwaddy Delta. Even so, the regime’s advantages in heavy weaponry, namely artillery and airpower, continued to mean daunting challenges for resistance forces and civilians in contested areas.

Stage three, when revolutionary forces would confine regime troops to urban areas, arguably began in late 2023. October 27th saw the opening shots of Operation 1027, a surprise offensive conducted by the Three Brotherhood Alliance in Shan State. (Operation 1027 refers to the date it began, using a convention that subsequent offensives would also adopt.) The Alliance—which consists of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Arakan Army (AA)—launched a series of simultaneous attacks on military and police targets in northern Shan State. The Mandalay PDF, the Bama People’s Liberation Army (BPLA), and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of the Communist Party of Burma also joined the offensive.4 By mid-November, the Alliance had captured over 100 regime positions and several towns, not least key border crossings such as the Kokang Self-Administered Zone after a crucial victory to seize Laukkai. The rapid collapse of regime positions sparked rebel offensives elsewhere, from Operations 1107 and 1111 in Karenni State to offensives in Karen State, Kachin State, Sagaing, Chin State, and Rakhine State. Along the Bay of Bengal, the AA’s gains in Rakhine State—their home territory, as it were, despite their training and operations in Shan State—have equaled or even exceeded those of the Alliance in the north, with speculation at the time that the entire state might fall to the AA.

Starting in June 2024, Operation 1027 Phase II has already captured a further 100 regime positions and a series of strategic towns. These include not only Nawnghkio but also Kyaukme, north of Nawnghkio and on the same trade route to the Chinese border, along which resistance forces are consolidating control; Singu town, only 91 km north of Mandalay and the first to be seized solely by the Mandalay PDF; Madaya, even closer to Mandalay, as resistance groups limit regime forces more and more to a defensive position in Mandalay; Mogoke, a large town famous for its ruby mines that neighbors Singu; and even Lashio, the largest city in northern Shan State. With a pre-offensive population of 350,000, Lashio is a major urban area. It also has a large airport and is, crucially, the headquarters of the regime’s North Eastern Command. It was the first regional command to be captured by resistance forces.5

This roughly three-stage revolutionary war has seen an evolving set of tactics. In the early phase, PDFs and EROs had to withstand attacks by regime ground troops along with gunships and fighter jets, all while staging attacks of their own. Airpower, notably, is not necessarily a sign of weakness or desperation, as some concluded too early, but a mainstay of counter-insurgency in the 20th and 21st centuries. In this first stage and into the second, resistance forces relied on speed, dispersion, camouflage, and the cover of darkness. They executed rapid, intense attacks at night or pre-dawn, overwhelming enemy positions and capturing weapons caches before quickly scattering to avoid air retaliation. In the second stage, a growing supply of small arms—namely Type-56 assault rifles (a Chinese version of the Soviet AK-47), and copies of the Type-81 that succeeded it—”turbocharged” the smaller PDFs of the Burman lowlands, allowing them to escalate hit-and-run skirmishes into more sustained and forceful operations. The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in the north and the United Wa State Army (UWSA) in Shan State (a major armed group but also nominally neutral) both have production capacity for Type-81 rifles. Both have supplied resistance forces. Further weapons have been trafficked across the Thai border, seized from army weapons caches, or produced by PDFs themselves, including grenades, rockets, and low-cost, battery-powered drones. By the time of the two-week siege of Lashio this July, conducted mainly by the MNDAA, resistance fighters used drones, rockets, and infantry assaults to make Myanmar military history by seizing the North Eastern Command.

Phase I of Operation 1027 already left the regime looking astonishingly fragile. A key observer called it the greatest battlefield challenge to the regime for decades—“by far the most difficult moment it’s faced since the early days of the coup.” The NUG declared its support for the operation from the outset, and in its three-year anniversary statement—in April 2024—described the regime as being “at its lowest point and on the brink of collapse.” Phase II has made for even greater territorial gains by resistance forces. Still, it is worth noting that the NUG, which sees itself as the leader of what is now widely referred to as a revolution, had no leadership role in this string of extraordinary offensives. The NUG could only take credit for the occupation of Kawlin in Sagaing, but the regime was able to retake and mostly destroy the town only weeks later. The nationwide uprising incited by the NUG back in 2021 barely belongs to it, if at all. Hence the biting remark from a Shan intellectual about 1027: “you know the NUG was not involved for two reasons: one, it was a surprise and two, it was a success.”

At the same time, the goal of state conquest articulated by the NUG with the notion of a people’s defensive war—conducted to establish a new “federal union”—is not the NUG’s alone. Across the rebel crescent and certainly around Mandalay and Sagaing, smashing the military junta is a widely shared objective, and the junta is the state. But the integration and coordination among PDFs (and between PDFs and EROs) that the NUG provides, has allowed their statist vision to filter at least formally across a wide variety of resistance forces, especially those PDFs with roots in the Burman lowlands. In this insurgent tendency, the national state, to be remade more or less federally, is the horizon of conquest and capture.

In many ways, this is the classical tradition of revolutionary theory and praxis. Revolution aims to found a self-determining new regime, a new sovereign order, within a grid of intelligibility owing to 18th century republican thought, translated across the former colonial world in the idiom of national liberation. Although revolutionary upsurges have always tended to contain more international, even internationalist, currents that exceed this frame of the state, revolutionary capture by radical republicanism has tended to obscure this excess. There is more than simply a state horizon to the current conjuncture in Myanmar as well, as we will see. But in the classical tradition, revolutionary success or failure, optimism or pessimism, reduces easily to one criterion alone: the capture of the state. This is why the cycle of struggles that has punctuated this century—from the Arab Spring to Occupy and beyond—has seemed so easy to dismiss for so many: those struggles did not capture the state, at least not durably.6

The insurgent tendency in Myanmar operates within this classical revolutionary paradigm. From this perspective, the insurgent bases across the rebel crescent and the Burman uplands operate as specific kinds of sites—of propulsive movement toward a new national sovereignty. The insurgent base makes possible a forward march of progress with its terminus in the state form. Recall that the acting president of the NUG, when announcing a people’s defensive war, spoke of an uprising that would occur everywhere, at once, for everyone, to safeguard equality for all citizens in a new federal union. This tendency sees Myanmar’s insurgent bases as akin to the guerrilla foco analyzed by Régis Debray, the philosopher famously imprisoned while traveling with Che Guevara’s guerrillas in Bolivia. For Debray, revolutionary armed struggle cannot limit itself to armed self-defense of territorial enclaves, such as the zones of peasant and worker self-defense in Colombia and Bolivia that he saw in terms of heroic, but wasted, self-sacrifice. By this logic, the armed struggle must also be “political” in the narrow sense of focusing on the conquest of the state.7 And in Myanmar, by April 2024, state collapse was imminent, according to the NUG.

Autonomy

However important the insurgent tendency is to this revolutionary conjuncture, it does not exhaust the current moment. With its outsized exiled presence in Western diplomatic circles, the NUG’s claim to revolutionary leadership makes it too easy to reduce the current armed struggle to a Cold War-style battle between dictatorship and democracy, authoritarianism and freedom—a struggle that again comes down to the familiar revolutionary criterion: capturing the state. That picture is far too simplistic. In actuality, the NUG has a Ministry of Defense but no army. Similarly, its vision of a federal union is highly contested. Throughout, and existing in a tense intimacy with the insurgent focus on state conquest, another tendency has also emerged, organized around land defense, territorial struggle, and autonomous administration. Though full of its own internal contradictions, this tendency does not, fundamentally, take as its sine qua non the capture and refounding of the Burman state-making project.

Across Myanmar’s rebel crescent, resistance forces were securing territorial and administrative control as early as late 2022, after the initial phase of strategic defense against regime attacks. In these liberated areas, autonomous administration has taken multiple forms. Larger and older EROs have already produced well-established civilian administrative systems developed over decades of rebel governance, which were extended to newly liberated areas. These systems cover a wide range of activities and services such as health, education, trade and economy, criminal justice, humanitarian response, and security—as well as issues like land tenure and natural resource management. In liberated areas administered by smaller and/or newer resistance forces, more basic governance includes activities related to public health, humanitarian aid, justice mechanisms, and countering illicit trade. In some places, namely states territorialized around specific ethnic categories, coalition councils have brought together politicians, political parties, EROs, and strike committees to form de facto interim state governments, including but hardly limited to the Interim Chin National Consultative Council, the Kachin Political Interim Coordination Team, the Karenni Interim Executive Council, and the Mon State Interim Coordination Committee. Meanwhile, the NUG has formed People’s Administration Bodies at the township level in areas controlled by NUG-aligned PDFs.

These administrations are precisely autonomous: they form and determine their own laws, administration, and governance. As one report put it, “ERO civilian administration wings and local coalition ‘councils’ are actively developing or strengthening their own governance systems, with an emphasis on local self-governance and self-determination.” In effect, these autonomous administrations make territory. In zones liberated from regime forces, autonomous administration produces embedded spaces—new and highly charged political spaces. Territory produced in this way punctuates and perforates the space of Burman state-making. The Burman state has long operated as the primary medium for enclosure, exploitation, and capitalist valorization—as the container within which deterritorialized, abstract space displaces, antagonistically, the sensuous lifeworlds of community, of everyday life, of daily survival. In response, today’s autonomous zones recast political organization beyond the conventional, centralized, nation-state form. Addressing subsistence from beyond the state, they are meeting the needs of survival, of basic provisioning, amid the collapse of Myanmar’s banking system, an economy in crisis, and key trade routes barely functioning—not least in northern Shan State and Kachin.

It is crucial to note that the autonomous tendency organized around land defense and territorial struggle is not a simple, unalloyed good—a singular, righteous protagonist that stands against the insurgent tendency’s tired loyalty, in effect, to the violence of Burman state-making. In particular, a distinction can be drawn within the autonomous tendency between communal forms of practical cooperation and reproduction that are addressing subsistence from below in difficult conditions—and the larger, more organized, highly mediated activities associated with the entrenched armed groups of the highlands, especially those of northern Shan State. The former move within the ambit of prefiguring emancipatory forms. The latter reproduce logics of social domination under conditions, greatly restrained, of self-determination. This distinction is necessary. At the same time, these two poles of autonomy exist along a spectrum. They push in different directions—spontaneous versus willed organization, in a sense—even if, per the critique of councilism’s opposition between the two, both are organic to historical conditions, hence not fully opposed nor entirely distinct.

At the frayed edges of state and market, what is at stake is not the romance of resistance so much as modes of practical survival. Self-organized subsistence means confronting the situation at hand to reproduce life under difficult conditions, using improvised, collaborative, and cooperative social forms.

Communal forms

In Myanmar’s current rupture, autonomy operates under the partial suspension of state and market rule, by a combination of imposition and volition. Across the rebel crescent, these zones of autonomy are not only the insurgent bases drawn from the 20th-century imagination of national liberation struggles—those sites of propulsive movement through time towards national space. Autonomy here might better be grasped within the historical legacy of the commune form, with land defense producing a political subjectivity less anchored to a transcendent national state. From the Paris Commune itself to more recent territorial struggles elsewhere—the ZAD at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, for instance, or Stop Cop City in Atlanta and the pipeline battles in Canada—communal activity aims for a reclamation of everyday life, reappropriating how space and time are lived. In Myanmar, a sharp distinction applies at all times between the national scale of the regime—renounced, resisted, held at a distance—and a more situated, more local, and self-organized orientation, where governance can take novel forms of association, such as the councils developed in Chin and Karenni States. Emergent circuits of social cooperation are answering questions of survival, subsistence, and security through self-organization—in the ruins, if incomplete, of state and market forces that never satisfied human needs in the first place. An alternative notion of revolution is at stake, centered not on the capture and refounding of a transcendent national state, but on practical solidarities that point beyond the state horizon—focused on addressing human needs.

Social reproduction looms large over the axis of autonomy. The problem of insurrectionary duration—at the raw center of any attempt to generalize a rupture in the political—ties into an everyday labor of basic provisioning: food, shelter, health, care. In rural Myanmar, this kind of labor is often a household affair. It has sustained and reproduced the possibility of armed struggle for many years, from the decades-long rebellions of the ethnic highlands to the people’s war being waged today. This revolutionary countryside is a refraction of the revolutionary household, in which gendered forms of emotional, physical, and material labor underscore the key role of women in waging—even while looking beyond—revolutionary war. Myanmar’s frontline is a landscape of broad devastation, but “within these harsh conditions, women’s labor… not only supports families and fighters but also provides a space for imagining alternatives to violence.”8 Acts such as collecting bamboo and firewood, cleaning one’s home and preparing food, or sending children and money to PDFs, can appear prosaic, commonplace, or routine. But they stitch together broken landscapes, animated by love for kin and the promise of alternate futures. All of this recasts the meaning and ambit of life itself. In Myanmar, “the gendered love and labor of making meaningful life is integrated with the broader revolutionary struggles, constituting the very essence of revolutionary politics.”

Across the rebel crescent, autonomy is tendential, not accomplished; it is a trajectory and orientation, not something complete or fully achieved. It marks a distance from and defense against the violence of Burman state-making (itself always tendential, rather than total), even while autonomous administrations, household provisioning, and social reproduction often reproduce, more locally—or can hardly avoid, no doubt—social hierarchy, market dependence, and gender inequality. At stake is daily survival more than total transformation. As in other situations of disaster, desperation, and armed conflict, people struggling to survive have formed communities of solidarity organized around care, cooperation, and subsistence. Akin to such disaster communities, they are “negotiating with their hands” to provide glimpses of self-organized reproduction that meets human needs—activities which the state views as threats.

Humanitarian activity, for instance, is both highly localized and very dangerous. Small-scale, community-based aid organizations have reported systematic attacks by regime forces on aid operations to displaced civilians, as the junta aims to isolate, strangle, and destroy resistance forces’ civilian base of support. Yet organized aid operations, however small-scale, are still just a fraction of what counts as humanitarian activity, broadly understood. Along the Thai border, Karen people have shown for years that “humanitarian protection” is something that ordinary people do for themselves, not something that formal organizations (small or large) provide. Against the backdrop of decades of insurgency and counter-insurgency in Karen State, self-protection involves measures like preparing hiding places in the forest in case it becomes necessary to flee, stashing food in the forest, and tracking troop movements to warn other villagers of army patrols. It can also include retrieving supplies from villages after fleeing, secretly tending to crops, setting up temporary “jungle markets” to trade with others in similar situations, sharing food with relatives and friends, relying on the forest for food and medicine, and creating basic education and social services in areas where displaced people settle temporarily or otherwise.

Activities such as these suggest that community, here, is best grasped not in the sociological sense of Gemeinschaft counterposed to Gesellschaft—the one simply organic and self-enclosed, a bounded world of static tradition, the other something open, formed through free association and rational self-interest. Beyond this stale opposition, it would be better to see community in Marx’s sense of Gemeinwesen: a being in common that, in moments of rupture and insurrection, people reconstruct and reclaim, prefiguring and producing a more authentic form of human community.9

Self-protection is not unique to Karen State. Such decades-old practices show how Myanmar’s revolutionary households are able to sustain and reproduce themselves under considerable duress even today—in movement and in flight, but also through acts of retrieval, reclamation, and reoccupation that hold open possibilities for return. In Sagaing especially but also elsewhere, PDFs are reportedly protecting land occupations by farmers. These are farmers who, for instance, are either newly appropriating land from industrial operations and agribusiness or reclaiming land they once held that had been seized by the military or state-backed businesses. Practices of self-protection, land defense, and self-organized reproduction help maintain the social fabrics that nurture and nourish, quite literally, armed struggle. They make it possible to raise, feed, and clothe the resistance fighters of the present.

Regime forces, symmetrically, aim to undermine reproduction in the countryside. Resurrecting its so-called “four cuts” doctrine, first developed in the 1960s, the junta is targeting food, funds, intelligence, and popular support for rebel groups. Raiding villages, scorching fields, and burning down homes, schools, markets, monasteries, mosques, and churches, for instance, are once again central to counterinsurgency. Arson looms large. Sagaing and Magwe, in the upper lowlands where Burman PDFs have been especially active, had already seen over 25,000 structures reported destroyed by regime arson attacks by mid-2022. Farmers’ land occupations have also been met by the reverse, depending on the balance of control in an area: land grabs by brutal, state-backed Pyu Saw Htee militias.

At the frayed edges of state and market, what is at stake is not the romance of resistance so much as modes of practical survival. Self-organized subsistence means confronting the situation at hand to reproduce life under difficult conditions, using improvised, collaborative, and cooperative social forms. Purity is in short supply—ideologically, politically, materially. In Tanintharyi Region, a research group embedded in rural villages, displaced communities, and armed resistance forces has argued for a flexible understanding of logistics. As PDFs and regime forces battle for control over trade corridors—especially the main road from Dawei to the Thai border—a proliferation of checkpoints and road closures means rebel camps and villages can get cut off from road access for days or weeks at a time. Crops wither before getting to market; shops close down; household provisioning becomes difficult. Here, the challenge of sustaining civilian support—the oxygen of any people’s war—is how to maintain some market access while struggling to control the roads. In this sense, logistics is a core object and instrument of armed struggle. Mastering movement, or trying to—of commodities, ammunition, and people, from civilians to resistance fighters to regime troops—is at the center of this people’s war. But resistance fighters cannot afford to totally shut down the roads and forestall movement (or for that matter to destroy the trade corridors in the area). The solution is to rearrange and recalibrate movement as carefully as possible. PDFs aim to provide for the movement of goods, guns, civilians, and fighters in ways that address simultaneously the demands of war, trade, and landscape: using some parts of the road network but not others, as needed; creating new paths through the forests, over hills, and across rivers, however laboriously and at great cost; and continuing to choke off, as best they can, supply lines to regime forces and army camps.

In the terms of one key debate, this is not a disciplined landscape of struggle. It does not seek control, mastery, or tactical direction from any global, overarching perspective. It unfolds, rather, like a process of inventory, where civilians and fighters alike take stock of what is available—what is open, what is possible, and what is not—in the environment at hand. This bricolage, so to speak, is conducted from the standpoint of partisans who are living and fighting from specific locations. Often besieged and beset by losses, their many victories nonetheless accumulate incrementally, rather than in one decisive moment. They are neither creating nor carrying out a master plan for the conduct of people’s war; they are navigating, situationally, a complex crisis of order. Deepening it, they take what they can to build something new.

Tanintharyi, it is worth noting, is more market-dependent than other parts of the rebel crescent. Over several generations, smallholder cash crops like betel nut, rubber, and seasonal fruits first supplemented, then largely displaced, subsistence production, especially in the lowlands but also in highland areas. More recently, sprawling state-backed palm oil plantations, proliferating to an unnerving degree, have accelerated this process of enclosure. This dependence on the market—this degree of market integration—explains why fighters in the south calibrate their orientation to the market carefully. In other parts of upland Tanintharyi and elsewhere across the rebel highlands, swidden agriculture is more common. Also known as shifting cultivation or rotational agroforestry, swidden supports as much as half of Myanmar’s highland population and covers up to almost a quarter of Myanmar’s land area.10 It involves cultivating a series of plots, one after another, and allowing abandoned plots to lie fallow while the land regenerates. Regulated at the level of the village through customary institutions, collective self-management, and reciprocal labor-sharing, swidden is oriented towards communal autonomy, common usage, and production for human needs rather than private accumulation. Historically, swidden reflected remoteness from markets rather than market integration—a way of satisfying basic subsistence rather than producing for valorization and profit. At the core of highland subsistence, swidden puts market distance, rather than dependence, at the center of material survival across much of today’s rebel crescent.

Autonomy’s contradictions

Autonomy is far from straightforward. In parts of Karen and Kachin States, rebel governance has a long history. Rebel groups’ civilian administration wings have worked alongside strong civil society networks for decades to govern populations and territory beyond—if always in tension with—the central Burman state. They know what it takes to keep and maintain territory after liberating it. For the newer groups constituting the Alliance in northern Shan State, rapid territorial gains have suddenly and massively expanded their area of operational control. For these EROs, with relatively little experience in rebel governance, acute challenges now impose themselves. They must secure and maintain things like water and electricity, health and education, transport and livelihoods, and safety and security. As regime airstrikes pummel recently seized territory, EROs are trying to govern against the backdrop of a genuine humanitarian crisis, with as many as three million people displaced across Myanmar—not least in northern Shan, where the robust civil society networks of other ethnic states are also comparatively absent. Even in Karen and Kachin States, where further offensives have also shifted the battlefield, expanding areas of territorial control mean daunting humanitarian challenges. By and large, these challenges will be locally met by ordinary people themselves, as they have been for many years even in Karen State, for instance.

The contrast between insurgency and autonomy arguably reflects a contradiction between statism and anti-statism, with a Burman revolutionary “leadership” focused on state conquest existing more or less in tension with a heterogeneous armed struggle organized around liberating autonomous territory. The NUG represents the first tendency, while the highland EROs represent the second. Somewhat less clear is where the Burman PDFs of the upcountry lowlands stand—aiming to liberate and defend their pieces of the countryside, yet within a political struggle in which state conquest remains primary. In this sense, the contradiction between insurgency and autonomy does not map fully onto the old distinction between the Burman state-making projects of the lowland—violent, coercive, and essentially hierarchical—and the anarchism of the ethnic highlands—putatively egalitarian, acephalous, and fundamentally anti-state.11 Still, it is inarguable that in a post-1027 conjuncture, major swaths of Myanmar are controlled by resistance forces whose relation to Burman state-making is, at best, ambiguous.

The national question comes down in part to whether a series of political concepts can mediate between insurgency and autonomy, between state conquest and the making of autonomous territory. These include federalism, a federal union, confederation, and devolution. The NUG and its closest ERO allies, such as the KIA, have consistently appealed to the promise of a federal union, wherein separate states and regions unite on the basis of negotiations to allow each to maintain autonomy under a shared sovereign order—with the exact degree of autonomy being the obvious question of negotiation. Only months after the coup, the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC)—an advisory body to the NUG that includes not only elected MPs, but also political parties, civil society groups, EROs, and coalition councils from ethnic states—published the Federal Democracy Charter. The Charter provides a legal framework for the NUG to act as the interim national government following the repeal of the 2008 constitution, drafted by the military in a way that protected its powers in the subsequent reform period.Within the NUCC, the MPs elected in 2020 voted to repeal the 2008 constitution the same day the NUCC published the Charter. Additionally, the Charter offers an interim constitutional framework to allow the NUG, coalition councils, and EROs to govern “with significant autonomy but under a common system of sovereignty.”

Yet this framework for a federal system has faced major difficulties. The second part of the Federal Democracy Charter, which provides a legal basis for interim governance in liberated areas—the question, that is, of autonomy for EROs, and to a lesser extent in areas controlled by PDFs around Mandalay and Sagaing—was in 2022 still seen only as a working document, neither accepted nor prioritized by all parties to the NUCC. Two years brought little progress. In April 2024, the NUCC’s Second People’s Assembly was widely seen as a failure. Representatives from the NUG and the group of MPs elected in 2020—the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH)—did not even attend the last day of the assembly, amid reported disagreements over the issue of autonomy in liberated areas. The assembly seems to have damaged relations between the Burman political establishment, congealed in the NUG and CRPH, and its supposed allies across the political landscape. Competing federal frameworks have now emerged, one by the NUG that expands on the Federal Democracy Charter and another from a group called the People’s Representatives Committee for Federalism.

Disagreement over defining federalism is not the only challenge. Some armed groups are hardly invested in federalism at all. The UWSA is Myanmar’s largest armed group aside from the regime’s military itself. With its 30,000 soldiers in the Shan-China borderlands—far more than the Three Brotherhood Alliance’s combined total—the UWSA has largely stayed out of the fight against the regime. Autonomy is certainly one of its watchwords. In Wa State, which has existed since the late 1980s, the UWSA-affiliated government issues its own travel documents; Myanmar currency is not legal tender (it uses the Chinese yuan in its north, and the Thai baht in its south); and a central party practices explicit self-governance, refusing formal allegiance to all neighboring governments—close relations with China notwithstanding. In Rakhine State, meanwhile, the AA appeared on the verge of taking the state capital, Sittwe, in the wake of Operation 1027 in Shan. Speculation was rife that, had it done so, its plan would be to negotiate with the regime to gain the kind of autonomy that the UWSA has secured. The AA understands such an arrangement not as federalism within a shared national union, but rather as confederation with serious devolution of powers. “In a confederation,” the AA chief once said, “we have the authority to make decisions on our own.” The AA prefers a situation “like Wa State,” he declared, explaining that confederation is “better” than federalism and “more appropriate to the history of Rakhine State and the hopes of the Arakanese people.”

To be sure, the AA’s activities in Rakhine State provide ample reason for concern about any eventual AA self-rule in Rakhine. In March 2024, reports emerged of the Myanmar military conscripting Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State to fight against the AA. The ironies are extreme. The Myanmar state denies Rohingyas citizenship; Rohingya people face a wide range of discrimination, including travel bans outside their communities. In the 2010s, Rohingyas faced mass violence at the hands of Rakhine civilians and the Myanmar military, with some 700,000 Rohingya people being driven across the border to Bangladesh. Over half a million Rohingyas remain in camps. Now, the Myanmar military has made cannon fodder of Rohingyas—dozens had reportedly died as junta conscripts by April 2024—while the AA targeted this population. As the AA battled the Myanmar military for control over Rohingya-majority townships in northern Rakhine in mid-2024, evidence emerged from victim testimony, eyewitnesses, and satellite imagery that suggested AA atrocities against Rohingyas—namely arson attacks on Rohingya villages and mass displacement of Rohingya civilians, mirroring the earlier expulsions of Rohingya that are now widely described as genocidal. In August, moreover, the AA used drones and mortars to attack Rohingya civilians who were fleeing across the Naf River to Bangladesh. The “beach massacre” was followed the next day by reports that, at the same river crossing, the AA fired indiscriminately on Rohingya civilians and, according to witnesses, committed acts of sexual violence. While the military’s conscription of Rohingyas made them vulnerable to AA attacks,12 evidence indicates that the AA is directly responsible for this new round of violence against Rohingyas—an ill omen for Rakhine self-rule.

The AA is not alone in preferring Wa-like self-governance. The MNDAA, the TNLA, and another ERO operating in Shan State, the Shan State Progressive Party (SSPP), are also reported to be deeply invested in securing expansive, Wa-like autonomy in a confederal system, rather than a federal one. Thus, while the NUG, the CRPH, and to an extent, Burman PDFs remain focused on capturing the national state, the strongest and most important EROs—the ones actually delivering crippling battlefield defeats to regime forces—are closer to a different aim: breaking the state itself, splintering it into a confederation of self-governing autonomous zones.

It is tempting to argue that the disruptive force of Myanmar’s insurrection lies neither in its conquest of the state nor in any anti-capitalist horizon (which would require a hard squint to see), but in the seeding of “anti-states” within a state, where alternative forms of political life can take root—forms of life irreducible to an over-arching, in-gathering state form, beyond the classical revolutionary trajectory from republicanism to national liberation. Yet as the above should make clear, Myanmar’s autonomous tendency is riven with considerable contradictions. At the level of self-organized reproduction in Myanmar’s revolutionary households—in the rebel highlands and upper lowlands—partisans, in place, are answering subsistence through communal forms. Their pragmatic solidarities intervene, impurely, in the immediate environment. These efforts, however tendential and inchoate, are addressing human needs amid the partial suspension—a crisis they are deepening—of state and market order.

But at another level of organized autonomy, not all rebel projects hold emancipatory promise. In Wa and Kokang, but even along parts of the Thai border and in the north, in Kachin, the supposedly egalitarian anti-states of the hills have long produced, in fact, highly state-like forms of political organization that reinstall social hierarchy, seek out market linkages, and map belonging onto relatively rigid ethno-racial categories. Wa State’s autonomy, for instance, is not autonomy from the rule of state or market. A centralized party leadership practices a robust political autonomy not from the state but from other states (Myanmar, China, Thailand), while maintaining market ties to them (through rubber and tea plantations, tin mining, opium production, gambling). If the armed groups of the Three Brotherhood Alliance achieve autonomy of this kind, then one can discern little promise of social emancipation. These groups are chasing a deeply ironic autonomy—at once muscular and frail, self-determined but within logics of overarching social domination.

In this sense, autonomy in the borderlands is not necessarily a sign of disorder, subversion, or the anarchism of the hills. Wa State, again, is better seen as stabilizing the surrounding sovereign grid.13 Since well before the coup, Wa State’s neighboring powers—China and Myanmar, of course, but also the Kokang area of control and to a lesser extent Thailand—have long tolerated this anomalous power. China strongly supports it. (The UWSA traces its roots to a splinter group from the China-backed Communist Party of Burma, following the latter’s implosion in the late 1980s.) The Myanmar state has been loath to antagonize such a close ally of China, not least a Chinese ally that is armed to the teeth and has 30,000 soldiers. China is often seen as an ally of the Myanmar junta, but the Chinese government also values stability on its frontiers, including the borderlands in northern Shan State where Wa State is located. Before the coup, the UWSA acted as a neutral buffer between Myanmar and China. It functioned as a power large and impartial enough to contain outbreaks of violence between other groups in the area and the Myanmar military. It is still seen this way, having played something of a stabilizing role in northern Shan even recently. It is this kind of autonomy—roundly accepted, grounded in military force, and expansive within its own state and market logics—that EROs like the AA, TNLA, MNDAA, and SSPP reportedly want. They are not fighting for whatever would come with a federal system rebuilt around a Burman power center in a conventional nation-state form.

A spectrum remains between communal autonomy and the more organized, mediated activities of key armed groups. Importantly, the spectrum these poles describe demands a political and material account of autonomy’s connotations—toward which we can only gesture here—in an environment that bears little resemblance to the conditions that shaped communist reflections on “autonomy” elsewhere, such as those of Italy in the 1970s or Chiapas and Rojava more recently. Even the adjacent historical legacy of the commune form, while helpful for shedding light on an emergent, self-organized political intelligence grounded in social reproduction and territorial struggle, is far more limited in its exemplars than what the present rupture in Myanmar suggests. Here, subsistence production, people’s war, and self-determination provide a matrix for grasping autonomy in terms irreducible to these other senses, which risk over-determining discussions of autonomy from afar.

Empire

In short: much of the world sees a heroic insurgency bent on reclaiming and refounding a liberal democracy, organized along federal lines. But that is only one tendency in this ongoing rupture—a highly limited one that, condensed in the NUG, carries little military force. In practice, material power lies with EROs: battlefield command, control over many trade routes, governance of liberated areas, and negotiations with regional powers, particularly China. Largely centrifugal, the visions of the most important EROs point towards Wa-like autonomous confederation more than any democratic federal union. For some observers, insurgency and autonomy are complementary tendencies—exactly the division of labor between politics, diplomacy, and leadership on one hand (the NUG), and battlefield expertise on the other hand (the EROs), that this moment needs. For others, the imbalance of power within this divided configuration signals an eclipse at last of the Burman political order, where centralized, nationally articulated military rule has long flourished. If that’s right, then it is less clear what kind of organization of power, what kind of sovereign grid, would follow.

China’s role—far more complex than the caricatures of Western critics allow—is helping to determine that grid. To its critics, China can appear as an all-powerful, all-knowing chess master, controlling ERO pawns in line with grand, decades-long strategies, while backing the Myanmar military to protect Chinese investments across the country. Yet Operation 1027 left the Chinese government reeling. The Three Brotherhood Alliance launched 1027 with tacit Chinese approval, as China used the offensive to break up cyber-scam syndicates that had grown in the Shan borderlands controlled by the Myanmar military’s Border Guard Force (BGF) in Kokang.14 But the Chinese government then hastily intervened to broker a ceasefire agreement between the Alliance and the regime that lasted only weeks. Known as the Haigeng Agreement, the ceasefire halted the offensive in Shan in order to protect China’s overland trade. In talks held in China’s Yunnan province, Chinese proposals offered the Myanmar military a secondary role in facilitating border trade, suggesting some formal presence for the military in Alliance territory in exchange for acknowledging the Alliance’s territorial control. That is, China sought local reconciliation under Alliance control with the goal of securing a vital trade corridor.

The agreement broke down quickly. By March 2024, tensions were already growing in Yunnan due to a grim trade outlook. The 2024 work report from the subprovincial government of Lincang City, which administers the area adjacent to Kokang, outlined ambitious goals: boosting trade by 15% and investment by 12%, while achieving 7% GDP growth. Other local governments in Yunnan set similar goals, but they all hinged on normal border trade with Myanmar resuming.15 In Myanmar, however, the junta paid little heed to Haigeng, with its goal of restoring border trade. The military used forced conscription to replenish its forces in Shan State as it planned for a counter-offensive to reclaim lost territory—hardly unnoticed by the Alliance. The Alliance moved to consolidate its territory in response while, encouraged by the KIA’s March offensive to the north, it advanced with plans to open an ambitious new phase of Operation 1027. China led new talks to head off that phase, but these also failed. Again disregarding the negotiation process, the Myanmar military began assaults on the TNLA, which in turn launched Phase II of Operation 1027 only weeks later.

The Myanmar regime continued to seek Chinese assistance to reign in the Alliance, especially as Alliance forces bore down on Lashio. The military’s leader, Min Aung Hlaing, offered to revive the Myitsone Dam, a major Chinese hydropower project suspended during the reform period. He made Chinese New Year a public holiday. And he sent former President Thein Sein to attend the PRC’s 70th anniversary celebration in Beijing. Chinese diplomacy also sought to maintain good relations with the military. As the Alliance made gains in Shan State, Foreign Minister Wang Yi met Min Aung Hlaing in Naypyidaw—his first high-level diplomatic meeting with China after years of failed diplomacy since the coup. In this meeting, Wang Yi signaled Chinese support for an “all-inclusive election,” according to Myanmar state media—one way among others to promote stability in Myanmar, from China’s perspective.

In fact, Chinese relations with Myanmar have shifted since late 2024. Tolerance for resistance forces’ gains against the military has dissipated, with the Chinese government putting renewed pressure on the Three Brotherhood Alliance to wind down their offensive in Shan State. In November, Chinese authorities placed the leader of the MNDAA, Peng Daxun (or Peng Daren), under house arrest in Yunnan. This followed MNDAA talks in Kunming with Deng Xijun, China’s special envoy to Myanmar, who demanded the MNDAA leave Lashio—a demand Peng reportedly refused. Meanwhile, Min Aung Hlaing attended a regional forum in Kunming, his first time being granted a visit to China since seizing power in the coup. Though he was not given a meeting with Xi Jinping, he met with China’s Premier, Li Qiang, who had two goals: first, restarting border trade, which China had closed down in order to push the KIA and the Alliance to stop their offensives; and second, resuming construction on a railway along the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, a series of Belt and Road projects that links Yunnan to Myanmar’s coast along the Bay of Bengal. Concerns over the security of Chinese investment projects, many of which are in areas now controlled by resistance forces, have also prompted the Chinese government to partner with the junta to create a joint security company—another topic of discussion in Kunming. This company, for which the junta is now drafting a memorandum of understanding, will be tasked with safeguarding Chinese projects and personnel. It will be an addition, in fact, to the four Chinese private security companies that already operate in Myanmar.

In other words, the Chinese government is trying to restore and secure bilateral trade by engaging with the junta and pushing resistance forces to stand down. They are, in effect, betting against any collapse of the military regime. Reflecting Chinese pressure, two of the three Alliance forces, the MNDAA and TNLA, have issued statements formally distancing themselves from the NUG. The MNDAA statement is instructive. It says the MNDAA is continuing to fight for “true autonomy.” As such, it will not cooperate with the NUG, either militarily or politically. It is also not fighting to break up Myanmar, seize state power itself, or create a new nation—nor to expand their territory or attack Mandalay or Taunggyi (Shan State’s capital). The statement also affirms the MNDAA’s right to self-defense, while it “urge[s] China to mediate and resolve Myanmar’s worsening crisis.” The statement is clearly an outward, expedient nod to Chinese concerns. (MNDAA relations with the NUG remain, though less publicly.) Still, it sharply underlines the core contradiction between insurgency and autonomy in Myanmar’s ongoing insurrection. It also makes clear that autonomy operates at multiple levels and meanings—along a spectrum that is not necessarily liberating.