This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news

Reflections on the post offices of Benzie County, Michigan, as a living map

Mary Welcome, essay & photography

The following is the fourth installment of “Reimagining Rural Cartographies,” a new Barn Raiser series exploring innovative and nontraditional forms of mapping. It is guest-edited by Lydia Moran and funded by Arts Midwest’s Creative Media Cohort program.

I have been organizing my correspondence lately: parsing out what to keep, what to save and where to put it. This is not unusual, as I have spent my whole life as a letter-writer, which in turn makes me a letter-receiver. My boxes of letters are meticulously ordered, a system divined into personal mythologies, geographies and devotions.

Dipping into the dangerous box where I keep lost love (both real and imagined) I read a letter from 2008, when J. was moving from one prairie state to another. His letter is about farmers measuring time and distance “as the crow flies” because you can see your destination coming when you live on level land. The shortest distance between two points is not only visible, but often evenly navigable in the prairie, especially for those traveling at an unmotored pace.

High plains states speculate in similar measurements: county boundaries were drawn with the county seat being equidistant from each edge community, schools were attended by students within walking distance, postal routes were established as a day’s ride on horseback.

If you look at post office locations on a map you get a chance to travel as that crow flies. The shortest distance between two post offices is also the most navigable; population density and difficult terrain are made visible by the frequency of post office stations.

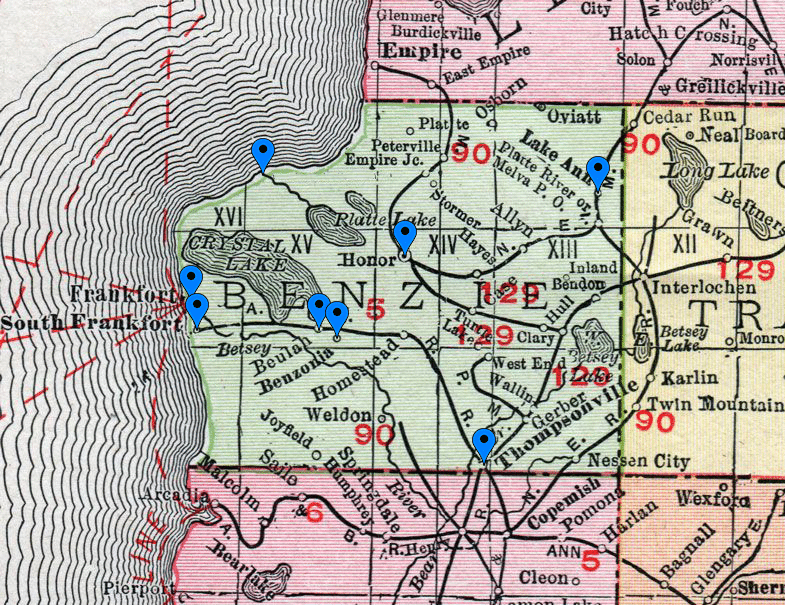

Post office locations in Benzie County, Michigan.

It is May 2012 and I am driving across the country sending postcards to a different lost love and picking up my letters via general delivery at one-man post offices in out-of-the-way places. Beside a gas station near Helena, Montana, the headline on The Independent Record reads “USPS Plan to Spare Rural Offices.” I don’t have enough change for the newspaper machine, so I read through the box window about community organizers turning the tide against the slated closure of 80 rural Montana post offices. This is the precise moment I start paying attention. This is the summer I became a post office portrait photographer.

God Bless the USPS is now an archive of thousands of my photographs, and it represents a long term research project about community correspondence. The photographs started as record-keeping—a way to map where I had been sending and receiving mail while traveling around the country. Like any practice of cultivating attention, visibility begets care, care becomes concern, concern shifts into advocacy and advocacy creates more attention.

The post offices of the Midwest, like this one in Sharpsburg, Taylor County, Iowa, have a unique tenor and improvisational architecture that reflect the cultural vernacular of the environments they serve. Planter boxes and benches out front are often maintained by community volunteers, interior decorations change with the seasons, grain elevators and water towers bend into frame.

The beginning of my project came at a crucial inflection point for the rural post office. Those community organizers I read about in rural Montana were responding to a much wider trend. In 2011, amid pressure to cut costs, the USPS announced it would close 3,700 locations, predominantly in rural areas. Many rural residents organized letter writing campaigns to Washington D.C., protested outside postal branches and purchased stamps and P.O. boxes to boost revenue. Some were successful and managed to help their post office survive; others weren’t, and saw their post office close, reduce hours or combine zip codes with another location.

Since then, an ever-lengthening record of post office service cuts has highlighted the deprioritization of rural communities. In 2021, Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, a Trump appointee, launched an aggressive austerity-efficiency-consolidation plan for the USPS, and, in the wake of the 2024 presidential election, has again called for slowing delivery to non-metro centers.

In September of 2024, the USPS announced significant service cuts: end-of-day collections will cease after the peak holiday season in every area more than 50 miles from an urban regional processing and distribution center. This slowdown in service will handicap approximately 23,000 of our nation’s 31,000 post offices and a whopping 47% of the population the USPS serves. City delivery will get faster and the rural routes will be less resourced. Lines of communication are drafted, drawn and erased by the availability of a postal service: a new rural cartography delineated by a shared communications commons.

The remaining rural postal network serves as a living map of relationships, historical narratives and landscapes across the Midwest. Rural communities rely on the post office for more than just mail: it is a critical space for community news—both by word of mouth in the conversational space of the counter—and through bulletin boards.

In my rural social fabric, Washington’s Palouse prairie, the neighbor-to-neighbor relationship of postal services are frank and indispensable. A portrait of a post office can serve as a portrait of a people and a place, illustrating both the institutional and intimate relationships sustained within and throughout their use.

A community bulletin board at the post office in Gooding, Gooding County, Idaho.

I spend my summers up in Benzie County, Michigan. In the early afternoons I walk to check my post office box in Elberta before Jerome closes up at 2:00 p.m. He is a musician and I am an artist; he works for the post office and I send mail every day. Our conversations are modest but friendly, and I stretch my questions out over many days of mail drop-offs. This year, I made a new portrait of the Elberta post office because I’ve started doubling-up on the archive; it’s nice to see what’s different over time.

I want to figure out who carved the massive wooden eagle mounted above the entrance of the post office in neighboring Frankfort. It has survived outside over the past 80 Michigan winters.

A wooden eagle, created by an unknown artist, welcomes patrons to the Frankfort, Benzie County, Michigan, post office.

One morning this summer, Andy Bolander, the community historian, walks over to sit in the sun on my front porch. He lets me ask him every question I can think of about the history of postal systems in Benzie County. He tells me the story of the sinking of the Ann Arbor #4 in 1923, a car ferry that delivered mail, goods and passengers to Betsie Bay. He tells me about “halfway houses,” places where mail could be passed along for pickup before formal postal systems were established. He tells me that there was an amusement hall with an underground bowling alley that also served as the post office in the early days of Frankfort. He has no idea who made the wooden eagle but promises to follow-up with any leads.

Later, I swing by the Frankfort post office to see if I can catch a conversation in the late afternoon lull. The clerks are happy to chat. Nobody knows who made the eagle. I mention that I’m working on an article and the whole place goes quiet. They pass me to the postmaster, who is having lunch in his office, and he comes out to tell me that postal office employees are not permitted to talk to the press. Any questions from the media, he says, must be directed to the regional headquarters, three hours away in Grand Rapids. He apologizes, gives me a number to call and wishes me luck. I leave a voicemail but never hear back. In my past 10 years of interviewing postal workers, this is the first time I experienced this barrier.

The statute on conversational research does not extend to postal retirees. Tim Flynn spent 33 years working in post offices across rural Michigan. “I always say, you get to know everyone in a community pretty well,” he tells me over the phone. “You have a chat with everyone that walks in that post office door. You know the families, the parents, the grandparents, the summer visitors. You watch the kids grow up and come to the post office on their own.”

Flynn tells me about parents using the postal scales to take the weight of their new babies because it was easier to get to the post office than the doctor’s office. He tells me about a letter carrier in Copemish that saved two people’s lives during a hard winter on her rural route and still made it back to the office in time to get the day’s mail out. As with most things rural, the post office stays nimble and resourceful, despite all standardization. “When you move post offices, you start over. You start making a new map of another 500–600 people you’re going to become friends with,” says Flynn.

The post holds fast by the work of the half a million hands it takes to pass a note across geographies. In Benzie County, the crow flies in concentric community circles rather than straight lines. Through history and mystery, the deer trail turned to footpath turned to backroads turned to a rural delivery route that connects person to person. It’s nice to see what’s different over time.

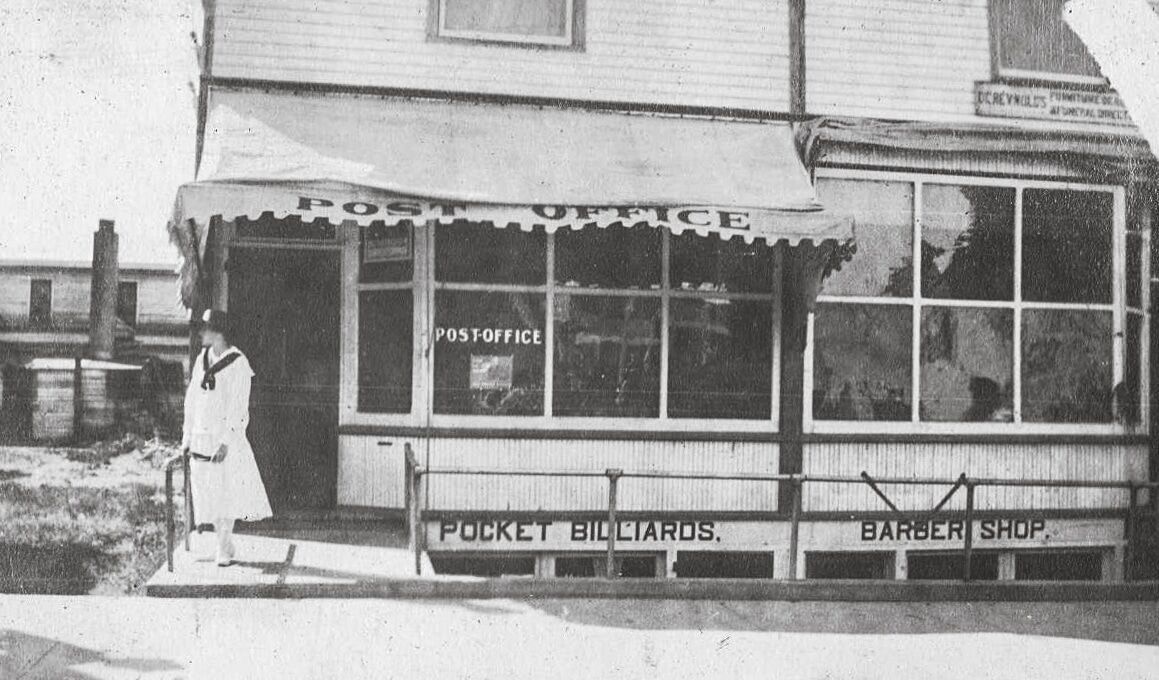

Below are historic photos of Benzie County post offices juxtaposed with the same post offices today, as featured in God Bless the USPS. (Navigate between the past and the present using the arrows.)

Benzonia (Population: 551)

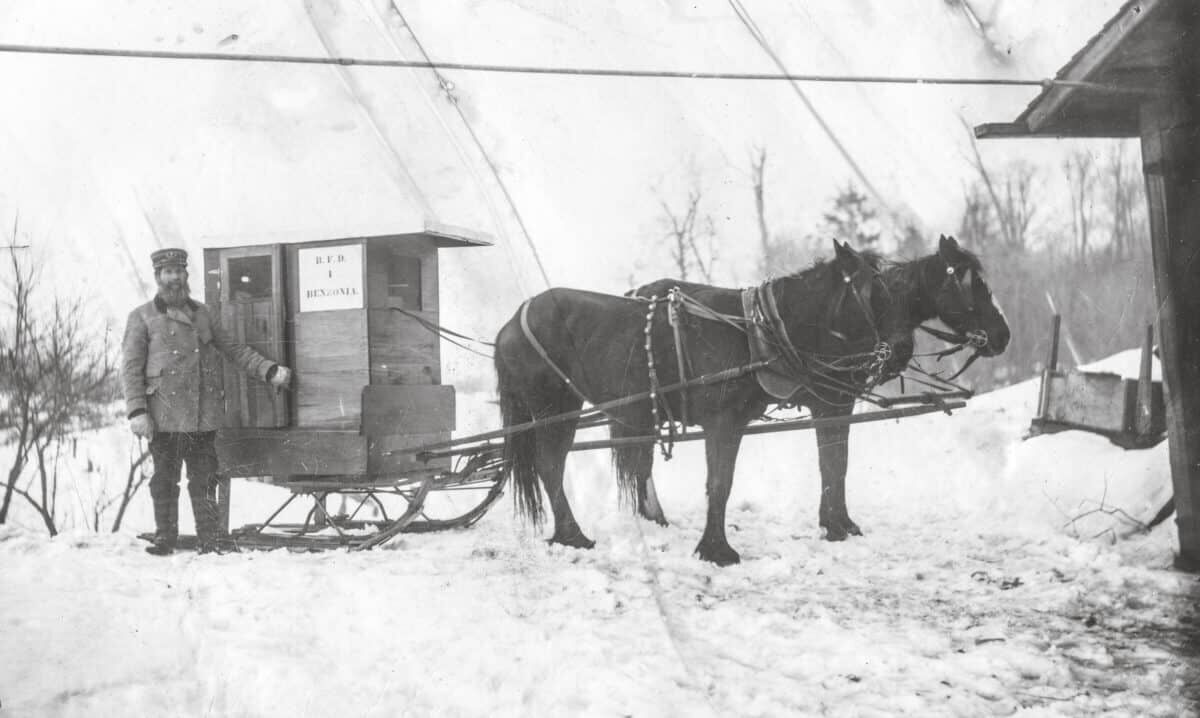

Letter Carrier Wallace Nutting for Rural Free Delivery by USPS in Benzonia (1903). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan.

The community called Benzonia started as an educational Christian colony in 1858 and it is home to the oldest post office in Benzie County. In 1859, “the post office was moved from Herring Lake to Benzonia by water and at one time in the course of the trip postmaster, postoffice, mail and all got wet when a wave on Lake Michigan upset the whole outfit.” As was typical of the times and fluctuating populations, the post office location leapfrogged from building to building across town. To this day, observers can still find outlines of letter slots on downtown buildings that formerly served as the post office.

Because of its history as a colony project, the community operated without developed transportation infrastructure during its early years. “Great inconvenience was experienced in consequence of the absence of roads … The mail route from Traverse City to Manistee by way of Benzonia was only a trail or foot-path marked by blazed trees. In summer the mail was carried on horseback; in winter on a sort of sled, not unlike the dog sledges in use in some arctic countries. It consisted of a single plank, eight feet long and a foot and a half wide, turned up in front like a sleigh runner. On this the mail bags were securely fastened by straps passing over them. The plank was drawn by a single horse, scarcely sinking into the snow and running over fallen trees without difficulty. The driver usually ran behind, but when fatigued sometimes rested himself by riding.”

Source: The Traverse Region, Historical and Descriptive: With Illustrations of Scenery…” ; Chicago: H.R. Page & Co.; 1884. Improvements at Benzonia Post Office Recalls Many Incidents of Early Days. Clipping, Benzie County Historical Society. History of the Benzonia Post Office. Benzie Record, Nov. 8, 1962. James Milliron, Benzonia Postmaster.

Elberta (Population: 329)

Post Office in Elberta, Michigan (1959). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan

Elberta is one of the smallest villages in the smallest county in the state of Michigan. Earl Moyna started his career as a letter carrier in 1920, on an Elberta route of a standard postal length: as far as a man on horse could reasonably travel in one day. This 30-mile route provided mail service to over 100 families. Patrick Moyna recalled going out on the mail route with his father in a 1996 edition of the Benzie County Record Patriot: “Patrons often waited by their mailbox to buy stamps, to tender some choice bit of gossip or to hear the ‘dirt’ from farther up on the line. Some left fresh baked-goods in the box and, on the coldest days of winter, Mrs. Brandt would leave a small thermos of hot, spiced brandy to warm us up. There was an oft-repeated ritual when we would stop: ‘Say Earl, who’s that fella with ya?’ ’Oh that’s my star boarder.’ Then they’d both erupt in laughter. I must have been 6 or 7 years old before I learned the meaning of that old Irish chestnut referring to a free-loader such as a do-nothing brother-in-law.”

Source: Benzie County Record Patriot, Nov. 27, 1996.

Lake Ann (Population: 273)

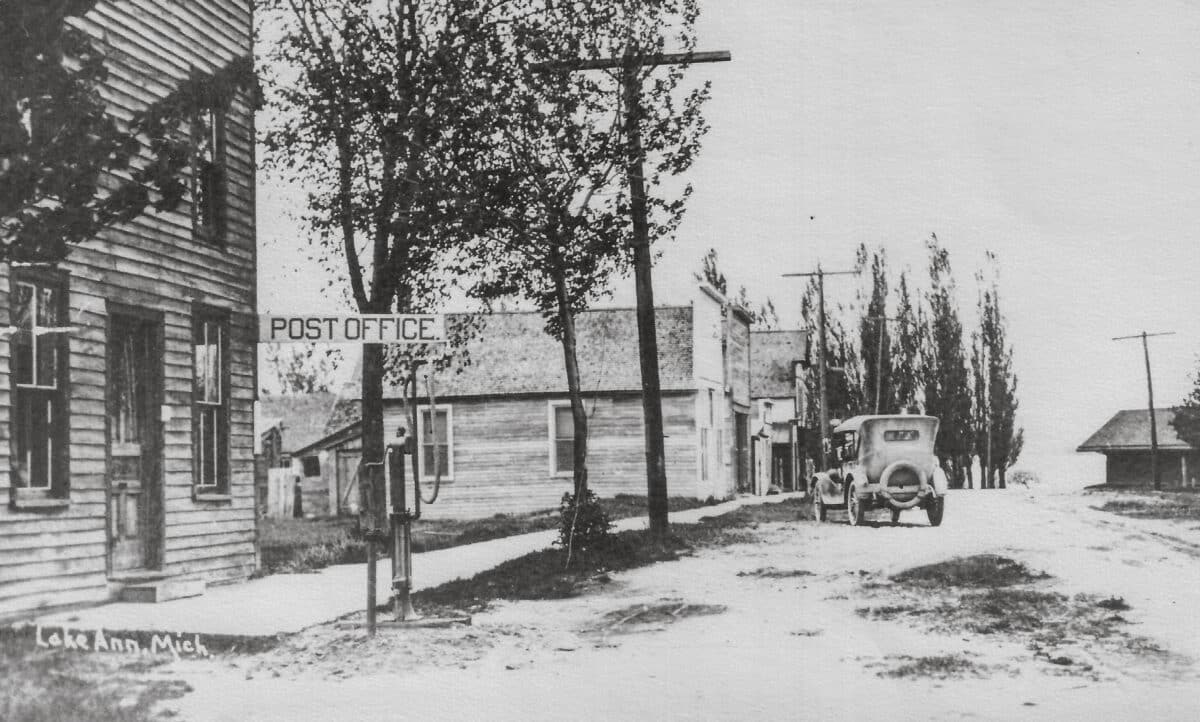

Post Office in Lake Ann, Michigan (1920). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan.

The first established rural mail routes were mapped via person and landmark rather than established roadways or specific addresses. Stanley Beckwith, of Lake Ann, tried to summarize an early mail route from Lake Ann in a book of local history: “The route went up cemetery hill. First stop was Louis Hermantle, then Lakeview School to Dan Willards, George Linkletter, Bob and George Barber (Bob lived where the Hawks later lived), Huffine’s on the left corner, Nick Nelson, and then Burnt Mill—Silas Woodcock’s home (Silas lived between the two Woodcock lakes) to Mike Doyle, to Cripes. Take a road to the left …turn left at Almira and deliver and then backtrack to Almira school … at the corner turn left but deliver to the Whites, Keumins, Brooks, Fullers … Again turn left to Stevens, turn right to Yeltzers, Melmorrey, Roblec, Greenbriar School … past Fred Goin’s place and curve around … turn right at the corner and deliver Beckwith, Hersey, Haywood, Somers and then to the corner … and back to the post office.”

Source: Lake Ann—Small But Friendly: A History of the Village of Lake Ann located in Benzie County, Michigan. Emily Traavis Brosier. Bayside Print, 1997.

Honor (Population: 337)

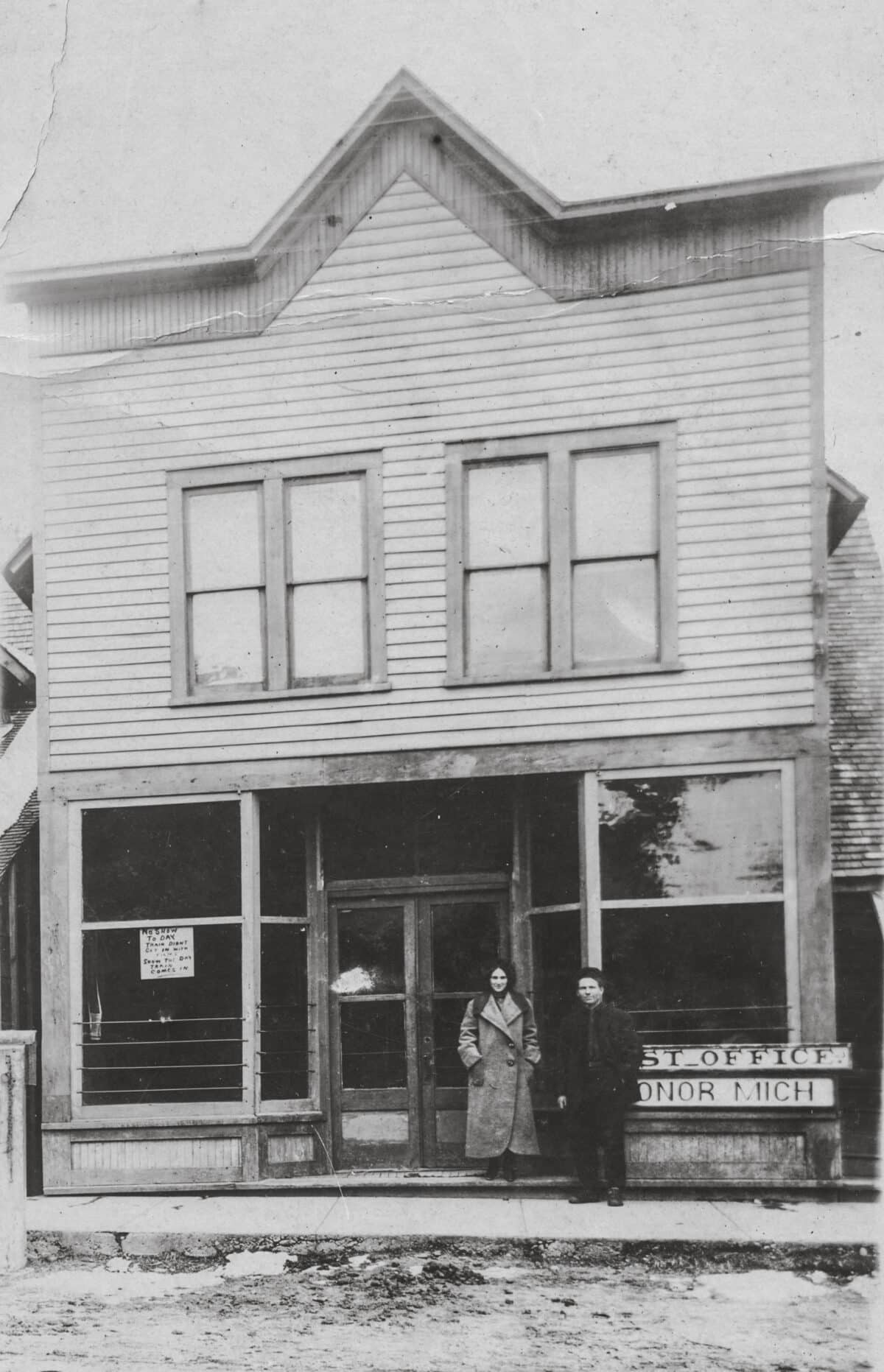

Post Office in Honor, Michigan (1913). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan.

L. K. Nicol started carrying mail in the winter of 1915 on a 25-mile route; he used a specially built stove-heated box, mounted on skis and drawn by horses. By winter of 1924, he had installed caterpillar treads on an old Ford chassis and rode in a covered box. During his long tenure as a postal worker, he “prescribed for the ills of both patrons and animals, called the doctor, brought groceries, matched thread, burned hornets nests, read and wrote letters, cut their fences and helped himself to their gasoline and sometimes even put their mail in the wrong boxes.” He received many gifts over the years, including “butter, eggs, cream, meat, chicken, fruit, vegetables, money and even jewelry. One patron gave him a possum, but the family refused to eat it.”

Source: L.K. Nicol ends Mail-Carrying Career. Clipping, Benzie County Historical Society, #20381.

Thompsonville (Population: 451)

Letter Carrier George Bell for Rural Free Delivery by USPS in Thompsonville (1904). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan.

As a village, Thompsonville grew around a railroad junction of two major lines: the Chicago & West Michigan and the Frankfort & Southeastern. The Railway Mail Service was the primary operator in this community, as the region’s mail was sorted by mail clerks on the trains working 10-12 hour shifts and then dropped off at the diamond junction. Like most towns in the aftermath of the Civil War, Thompsonville historical records make mention of their one-legged postmaster.

Source: Thompsonville, A History. Bryce Gibbs. University of Michigan, 1976.

Frankfort (Population: 1,252)

Post Office in Frankfort, Michigan (1941). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan.SPS.

As Benzie County’s only city (all else are designated as villages, townships, census designated places or unincorporated communities), Frankfort stewards the largest delivery network and a sizable post office to accommodate it. The historic building was constructed in 1940 with federal funds from the Treasury Department and houses a post office community mural, one of the New Deal artworks organized by the Treasury Section of Fine Arts. Artists were employed to work with communities to create murals that were specifically representative of their place for installment in local institutional buildings. Henry Bernstein painted “On Board the Ferry Car (Ann Arbor #4, Feb. 14, 1923),” which depicted car ferry workers struggling to secure the railroad cars while battling a ferocious winter gale on Lake Michigan. Car ferries were a critical link in Michigan transit, and the Ann Arbor #4 was a steel twin-screw cross lake passenger and railroad ferry responsible for carrying people, cargo, railcars, goods and the mail across the oceanic lake.

Source: The Living New Deal Project, Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-4740.

Beulah (Population: 313)

Post Office in Beulah, Michigan (1920). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan.

Beulah’s half-mile township sits on a strip of land that was underwater for millennia and exposed during an engineering experiment gone wrong when Crystal Lake was mistakenly drained into Lake Michigan by county leaders trying to construct a water-shortcut for shipping. Though small in population, Beulah’s downtown post office locations served thousands of seasonal visitors due to the smelt boom at the turn of the century, the world famous Cherry Hut and growing resort communities.

Aral (Population: 0)

Post Office in Aral, Michigan (date unknown). Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan.

Now the site of one of the most popular swimming beaches on Lake Michigan, the ghost town of Aral rose and fell with the boom-and-bust of the timber industry in western Michigan. The two-story sawmill employed folks from all over the area and the post office served as the communications hub for about 200 residents, including a community of 50 Odawa/Ottawa families that would come to Aral each winter to work in the lumber mill.

Source: Wayside Marker, Remembering Aral. Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. National Park Service.

Teaser image credit: Letter Carrier Wallace Nutting for Rural Free Delivery by USPS in Benzonia, Michigan (1903). (Courtesy Andrew Bolander at the Benzie County Historical Society, Benzonia, Michigan)