A decentred leaderless movement aims to shut down France on 10 September in a powerful attack on the bankruptcy of Macronism

~ punkacademic ~

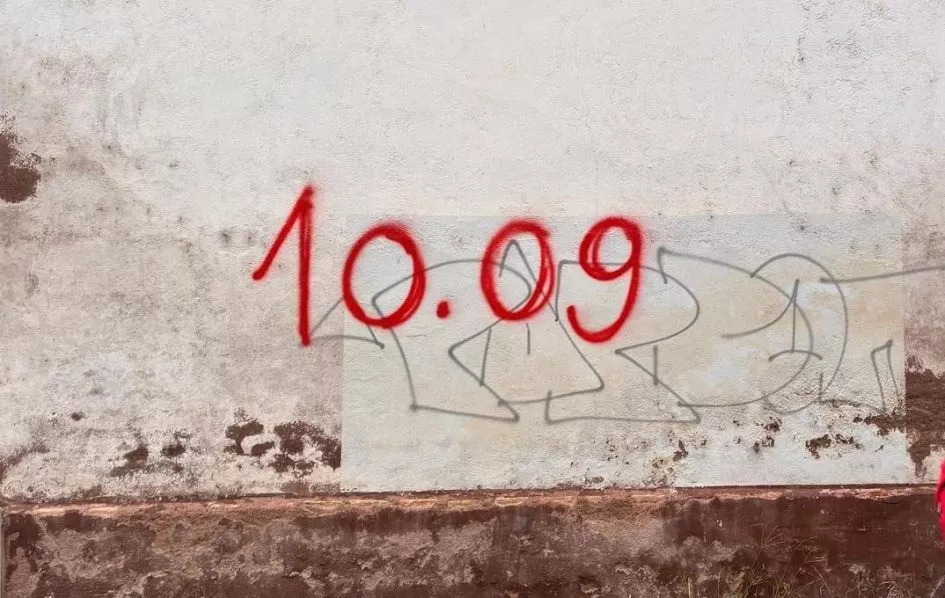

It’s unusual that the loss of a Prime Minister and their government might not be the worst thing to happen in a week for a sitting French President, but this week might be the exception. Emmanuel Macron’s intellectually-bankrupt political project hit the skids again on Monday night when his Prime Minister, Francois Bayrou, was compelled to resign after losing a confidence vote in the National Assembly. The writing was on the wall (literally, in some places) – the reaction to Bayrou’s proposed austerity budget, which would have frozen pensions, implemented 44bn in cuts, and axed two bank holidays, had made his demise inevitable.

But a greater threat to Macron looms; the threat of direct action on the part of a leaderless, decentralised movement, which has one simple call to arms – ‘Block Everything’. The bloquons tout, as they are known, originated online and have evolved into a mass movement which has drawn parallels with the Gilet Jaunes (Yellow Vests) of 2018-2020, but which has a vastly different political profile.

With many participants aged between 25 and 34, the bloquons tout are often graduates and hail from a different end of the socioeconomic spectrum than the disappointed retirees who manned the Yellow Vests’ blockades. These rebels are of the left, as recent research has shown. With mainstream political parties and unions not wanting to miss out on a train leaving the station, they have drawn support from the CGT, the Socialist Party, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise.

The energy comes from outside the parties and unions, however, with the French authorities preparing for significant disruption in centres of left-wing activism including Nantes, Rennes, and Lyon. The Federation Anarchiste is mobilising in Rennes, Paris and across France, manning blockades, encouraging workers to strike, and broadcasting an online radio show covering developments from the participant perspective.

French analysts are divided on whether Bayrou’s resignation will draw the sting of the Block Everything movement, with some claiming the fall of the government will demobilise the protestors, whilst others claim it will ‘galvanise’ them. Estimates from the French security establishment that 100,000 people can be expected to take part across France seem like wishful thinking on their part and an attempt to demotivate protesters.

Block Everything represents a rejection of conventional politics that has repeatedly been shown wanting in France. In mid-2024, following a disastrous political gamble in calling an election to face down Marine le Pen, Macron’s determination to freeze out the left-wing New Popular Front which had gained a plurality of seats has led to crisis after crisis and a revolving door of Prime Ministers.

Each time a Macronist Prime Minister seeks to raise the rhetorical temperature in political terms is a clearer demonstration than the last that French political institutions cannot deliver the change younger voters want and need, with some economists claiming the fiscal ‘crisis’ has been blown out-of-proportion.

The Federation Anarchiste is using this moment as a teachable one, with comrades using the venues and spaces opened up by the 10th November day of action to communicate the nature and possibilities of anarchism. Though one pundit (rightly) stated that the CGT has strayed far from its revolutionary roots at the dawn of the 20th century, their ability to close down workplaces remains pivotal. Calls for a general strike have been heard from the left.

Though a general strike is unlikely, workplace occupations and cross-sector action have been mooted. With air-traffic controllers also set to go out on strike the following week, the potential for continued disruption is real.

‘Block Everything’ promises to be significant, with some pundits claiming it could witness the biggest turnout since the May ’68 events. Whether it does or not, it represents a major challenge to Macron’s politics of zombie neoliberalism, with the mainstream press claiming France ‘may have become ungovernable’. We can but hope.