In her lifetime, Shulamith Firestone, an art school graduate and leading figure in New York’s second-wave feminist movement, published just two books. Her first, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1970), was a blistering theoretical salvo published when Firestone was only twenty-five. Amongst its more radical propositions, Firestone called for ‘ectogenesis’, the gestation of fetuses outside the womb via artificial uteri, and the abolition of patriarchal ‘love’ and the nuclear family.

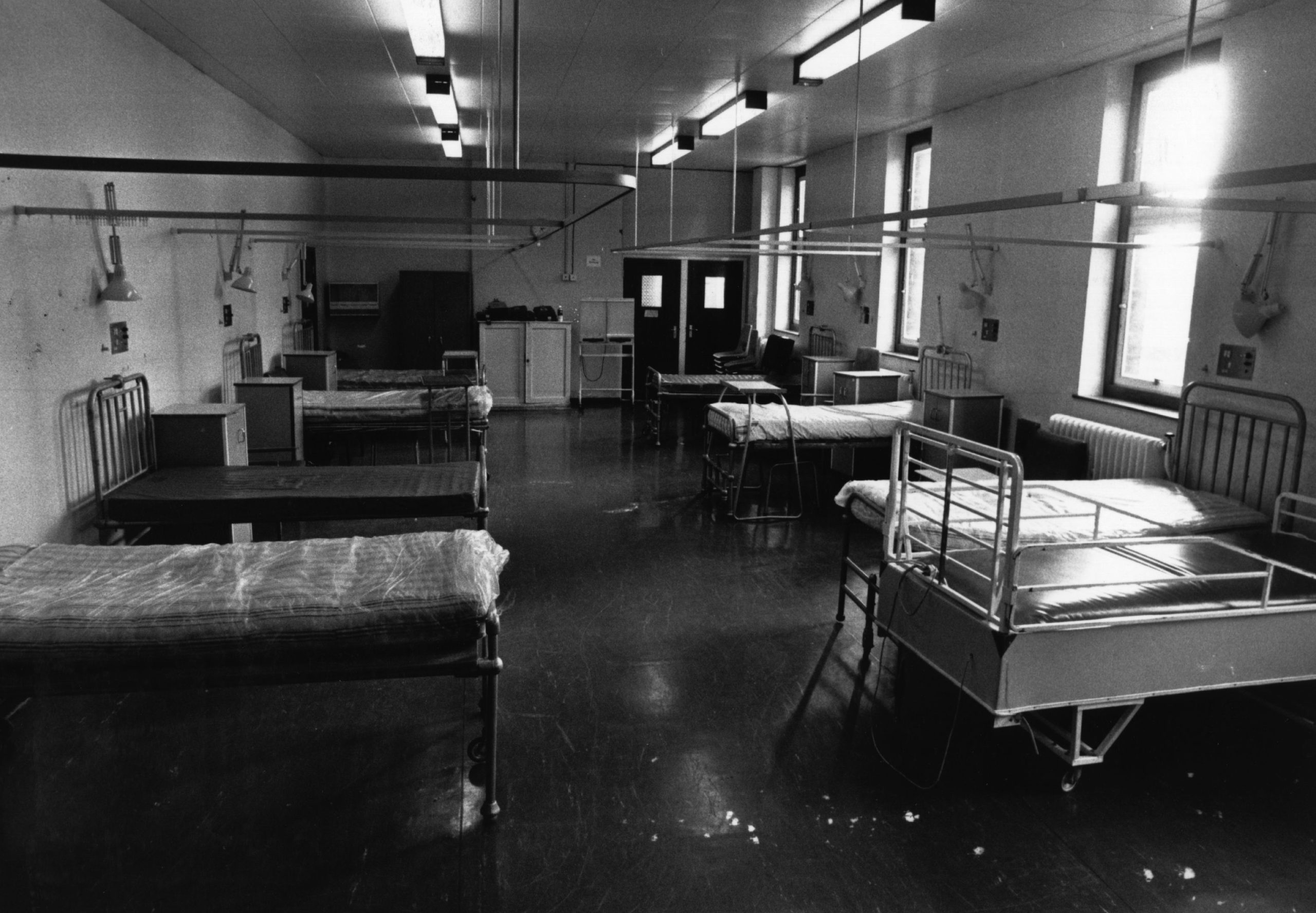

In the late 1960s, Firestone — ‘Shulie’ to her friends — co-founded a string of radical feminist collectives: the New York Radical Women, the Redstockings, and the New York Radical Feminists. By 1969, she was ousted from the latter, accused of being ‘too intellectual’ by her comrades. By the mid-1970s, Firestone had suffered a nervous breakdown, withdrawn from activism altogether, and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. She would spend the rest of her life in and out of the hospital until she died in 2012, documenting the various horrors and indignities she endured there in Airless Spaces, a collection of short stories published in 1988.

When Silver Press reissued Airless Spaces earlier this year, the publishers included several thoughtful contributions from, amongst many others, writer Chris Kraus and Loudres Cintron, Firestone’s first mental health case manager. Cintron urges us to read between the lines. The book ‘starts in the outside world, not in a psychiatric unit, because the ‘madness’ happening in the ward is determined by what happens in our absurd open society.’ But this is also a series about ‘dysfunctional human relations, relations of power, abuse of physical and bureaucratic power, and broken dreams.’ Care coexists with coercion here, kindness with violence, and resistance with resignation.

Shulie was burned badly by her experiences in the Women’s Liberation Movement, an exile she returns to in the story ‘Myrna Glickman’. Through the avatar of Rozzie, we follow a woman who reconnects with a former friend who once sided with her rival to force her out of an egalitarian feminist collective, which eventually collapses under new control. At face value, we can interpret this story literally and autobiographically. But a fresh line of inquiry might compel us to draw parallels between Firestone’s time in 70s radfem circles and psychiatric hospitals. Both promised to care for Shulie and free her from the fetters of circumstance. Neither could.

In the three decades since Semiotext(e) first published the book, responses to mental health have arguably changed more than I’m sure Firestone could have ever imagined. Yet there seems, still, an impulse to treat mental illness in isolation from the systemic issues that might have exacerbated — or even caused — it. There is no therapeutic salve for bad housing or a collapsing job market; no way to think yourself out of the patriarchy or its violence. As we see in Airless Spaces, we can’t afford to dismiss the link between societal and mental illness. One often begets the other.

The eponymous character, ‘Debra Daugherty’, is one such casualty of a hard life. Though Firestone’s narrator claims she lives in ‘a cute little unit with a good bathroom’, the flat has a single window and a cockroach infestation. (Faludi notes that Firestone once had the same issue; when one on-again, off-again boyfriend saw her crush a cockroach in her flat, she told him: ‘That’s the story of my life.’) Then things take a darker turn when Debra reveals that her husband almost killed her on her honeymoon, tried to ruin her life (she infers that he might have tried to poison her), and turned her son against her. Debra’s brief inpatient stint is implied to be the aftermath of these traumas, as is her alcoholism. More cruel, negligent husbands crop up in ‘The Caregivers’: Brenda fights for custody of her daughter, while Bernice’s alimony isn’t enough to cover her shopping addiction.

Airless Spaces also has its fair share of bad families, too. In the caustic tale ‘Loving the Hospital’, Mrs. Brophy takes prolonged hospital stays, or ‘vacations’, as she calls them, for some respite from her maternal responsibilities: ‘she didn’t know how she could ever have gone without them.’ Marlene, the protagonist of ‘The March Fracture’, ‘leaned too heavily on her husband and lost him.’ After her foot collapses on a trip to the supermarket, she regularly runs out of food. Marlene tries ‘to get more hours from a home attendant,’ Shulie tells us, ‘but this request got swallowed in red tape because a march fracture was deemed a temporary condition.’ Even temporary conditions, she implies, have a way of becoming permanent when you’re poor and alone.

Firestone was as obstinately anti-family in practice as she was in theory. She dismissed the bio-family’s unequal power distribution between mothers and fathers; its treatment of children as property. So strong was Firestone’s hatred of her own father that she disowned him via Certified Mail after he spent years trying to subordinate her — insisting she perform domestic chores for her brothers, dismissing her objections, and punishing her for defying the gender roles he imposed, according to Faludi. The only family tie that Shulie thought worth saving was her relationship with her sister Laya, who has also penned a piece for the Silver Press reader. Laya understood her sister better than most, and certainly what she was trying to achieve with Airless Spaces; more than just deadpan vignettes, Firestone wanted her stories to be ‘into a world most people would rather ignore’, attentive not just to mental illness but also the ‘systems that suffocate the human spirit’.

Where Dialectic brilliantly gauges possible alternatives to the nuclear unit (the ‘three failed experiments’ in focus are the Russian commune, the kibbutz in Israel, and Summerhill, the Suffolk-based, democratic school for autodidacts), Airless Spaces discards this earlier, ambitious utopianism. It’s tempting to read Airless Spaces as an allegory for the second wave: Firestone shrinking, her presence dwindling, alongside the movement she helped build. Yet the book itself is brutal in its verdict, offering little but scorn for the feminist left’s idealism. At the risk of speculating why this may be, I find it telling that Faludi would use a quote that described the New York Radical Feminists coup as though Firestone had ‘been rejected by her family.’

Without adequate family or state support, without help from the revolutionary left’s mutual aid networks, what happens to women like Shulie? The answer is bleak, but so are the fates of the women — sick, disabled, elderly, broke and on benefits — that populate Airless Spaces. More than hospital horror stories, these are stripped-down portraits of survival under neoliberalism, where care is privatised and structural abandonment is dressed up as individual failure. The solemn, paragraph-long story, ‘Passable, Not Presentable’, describes how mental illness afflicts its narrator, who tries ‘to disguise the stiffness in her gait, and the drooling moronic look on her face that came from the medication.’ It’s difficult not to read these stories and think of the punitive cuts to disability benefits so many face today.

That Firestone kept writing, kept documenting, kept observing — even as a victim of the very structures she once vowed to raze — is not quite hope. But it is a cry against the disposability of certain lives and those abandoned by every social contract intended to protect them. What if we started from there? What if our politics did, too?