On 27 October 2023, the Sun and Daily Mail carried reports that British Special Forces had been deployed to support Israel’s campaign in Gaza. For the next 21 months, despite the hefty significance of the revelation, not a single mainstream media outlet considered it. This silence was later explained by the imposition of a government ‘D-Notice’, issued to news organisations immediately after the reports, requesting that the story not be pursued further. The press dutifully complied.

D-Notices initiate what the journalist and academic Roy Greenslade once described as a ‘peculiarly British arrangement’, in which media outlets voluntarily agree to their own censorship at the government’s request in the name of ‘national security’. The arrangement has its origins in the build-up to World War I, when the Admiralty and War Office introduced a protocol of voluntary notices to newspaper editors advising them not to publish information such as naval deployments, troop movements, and the arrest of enemy spies.

Although this system of voluntary censorship remained in place during the interwar period, it was superseded during World War II by a Ministry of Information apparatus that issued binding daily directives to the press. This directness was rolled back after 1945, but the earlier voluntary system was formalised with the establishment of the Defence Notices Committee in that year (from which the D-Notice takes the name).

As both public and journalistic expectations of press freedom expanded, tolerance for the overt censorship deployed in wartime declined, giving rise to voluntary gagging orders as the preferred instrument for concealing state secrets. This shift also reflected a broader change in Britain’s global role. In the Cold War era, as more transparent styles of imperialism became politically untenable, foreign interventions increasingly took the form of covert operations, proxy conflicts, and alliances with authoritarian regimes. Lacking the legitimacy of a global war against Hitler, these activities were better concealed through a mechanism that was voluntary, opaque, and free from legal oversight.

The Ornamental Press

The committee, renamed the Defence and Security Media Advisory (DSMA) Committee in 2015, has remained largely unchanged since its creation (the notices themselves were rebranded in 1993 as Defence Advisory Notices, though still widely known as D-Notices). Comprising senior officials from the Ministry of Defence, intelligence agencies and other departments, the committee also includes representatives from major media outlets, although they play no role in shaping notices. In theory, their function is to advise on the system at biannual meetings, though its static nature suggests a more ornamental, impassive role.

When a story is deemed a national security risk, government departments or intelligence agencies contact the DSMA Secretariat, typically a retired senior military officer, who then issues a D-Notice to media outlets advising them to withhold or redact the story. If a media organisation uncovers a story they believe involves matters of national security, there is also an expectation that it be submitted for the committee’s consideration.

It is important to emphasise that D-Notices are purely advisory and issued on a voluntary basis. If a media organisation deems the information covered, including the existence of the notice itself, to be in the public interest, there is no legal barrier to publication, although there may be criticism. Examples of defiance in the face of government overreach, however, are astonishingly rare.

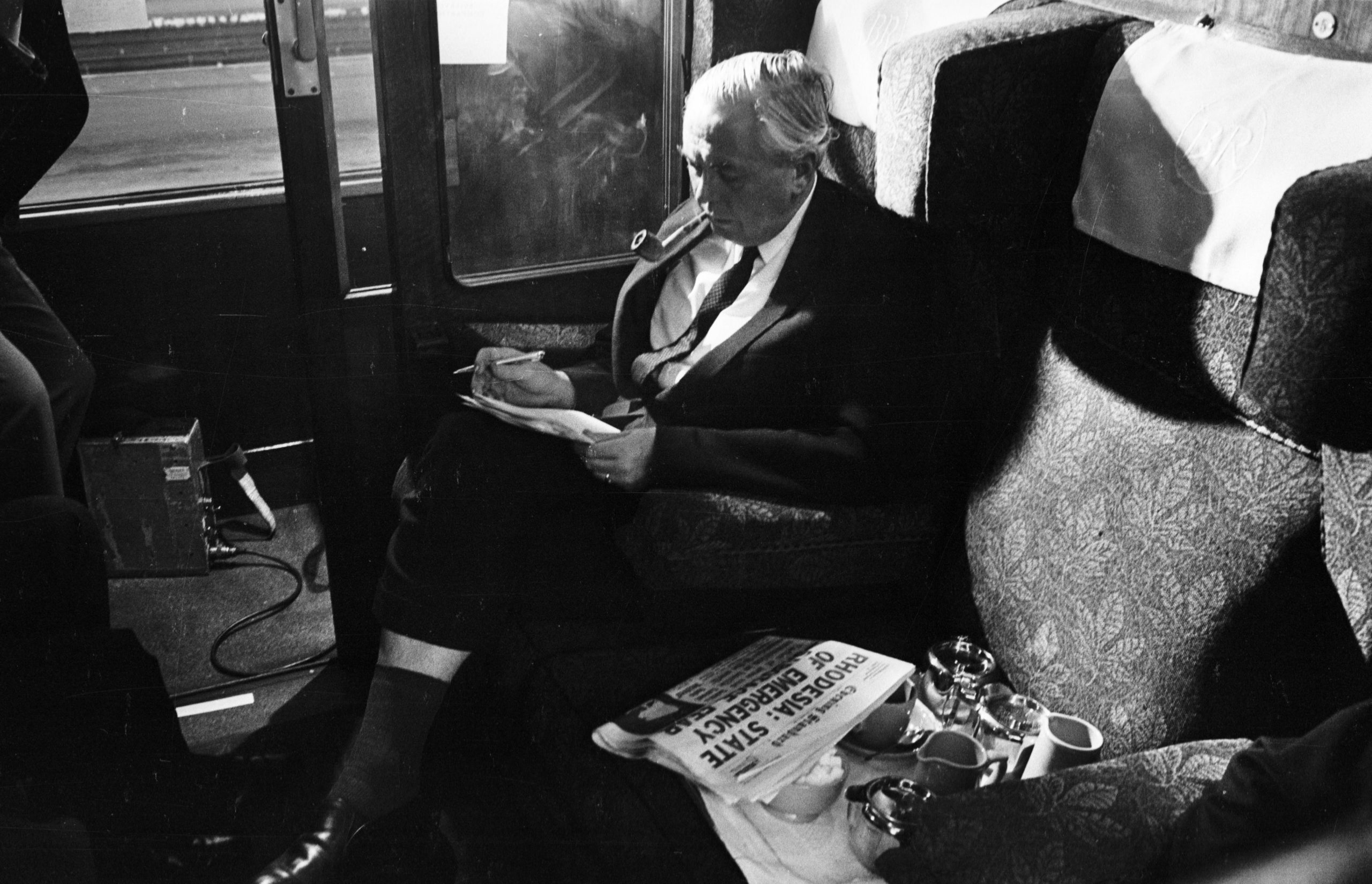

One such case occurred in 1967, when the Daily Express published revelations that the government was secretly vetting overseas telegrams, prompting Prime Minister Harold Wilson to state in parliament that the paper was breaching D-notices. The paper denied wrongdoing, claiming it had cleared the story with officials beforehand. A public row followed, leading to a Privy Council inquiry and the resignation of the D-Notice secretary. In its aftermath, broad categories of sensitive material were laid out where editors were expected to consult with the committee before publishing. The affair dealt a major blow to the system’s credibility, though it ultimately survived.

Another notable challenge to Britain’s state-media secrecy apparatus came in 2013 with the Guardian’s publication of the Edward Snowden revelations. These reports exposed an illegal global surveillance operation led by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and its allies, including Britain, which included the secret mass collection of phone, email and internet data. The Guardian published the scandal without first consulting the DSMA and, after a notice was issued, reported on its existence and refused to comply with all its advisories.

An international uproar ensued, not only over the government’s unlawful surveillance but also over its attempts to censor subsequent media reports. Nevertheless, agents from GCHQ, the signals intelligence agency exposed in the Snowden disclosures, visited the Guardian’s offices and oversaw the physical destruction of hard drives and laptops containing the files, despite the lack of any court order or legal compulsion. This episode helps explain the publication’s more compliant editorial posture in the years since.

Not every media outlet is so easily cowed. Declassified UK, an investigative journalism outfit focused on exposing Britain’s foreign policy and its military and intelligence agencies, is a rare case of a publication willing to openly challenge the D-Notice system, often reporting on the existence of notices and the committee’s attempts to restrict its coverage. In early 2022, it revealed that British Special Forces were secretly training Cameroon’s elite military unit, despite its involvement in serious human rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings. When Declassified named a British officer overseeing the mission, the DSMA Committee sent a series of formal and insistent requests for the name’s removal. Declassified refused and published the correspondence, citing public interest.

Knowing When to Shut Up

State hostility towards media outlets that defy official but voluntary advice raises a question: why, if making such information public truly endangers national security, is formal censorship not used instead?

One answer is that legal injunctions require the government to convince a judge that publication poses an immediate and serious threat, rather than merely political fallout. This threshold is difficult to meet, especially when weighed against principles of press freedom. It also risks leaving a paper trail open to later scrutiny, something the more discreet voluntary approach avoids.

Another answer lies in the recent episode in which a High Court super-injunction barred reporting on a Ministry of Defence leak that had exposed the names of thousands of Afghan citizens who had worked with British forces, putting them at risk of Taliban reprisals, and even prohibited mention of the injunction itself. When the injunction was eventually lifted, it not only sparked widespread criticism from MPs and journalists for obstructing proper public scrutiny but also amplified the story far beyond what attention it might otherwise have received.

This contrast — between the furore over the Afghan leaks and the media blackout on British Special Forces’ involvement in Gaza — neatly illustrates the advantages of voluntary censorship. D-Notices work so effectively precisely because the media are more likely to cooperate when they believe they are acting independently and free from coercion. What is enforced through diktat or threat in more authoritarian states is, in Britain, achieved with willing compliance.

Nowhere is entanglement between press and state more apparent than in foreign policy reporting, where coverage of defence and intelligence often depends on carefully curated briefings from official sources. Cosy relationships are nurtured at events such as Defence Press Association luncheons, where journalists mingle with military officers and government officials in a relaxed setting, reinforcing deference and discouraging scrutiny. Journalism built on privileged access inevitably absorbs the state’s priorities, making dissent not only rare but costly.

The national security rationale that justifies obedience to D-Notices, too, is so entrenched that journalists rarely question it, instead internalising it as their own. This holds true even when there is no formal request to bury information. Some of the most damning evidence of Britain’s role in Gaza, such as the operation of daily spy flights, the training of Israeli soldiers and continuing arms sales to Israel, is already public thanks to independent outlets. Yet these stories are ignored by much of the mainstream press, without the government ever needing to intervene.

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of the D-Notice regime and the broader culture of media complicity is the scale of what is hidden. For every state secret that escapes through the cracks, countless others never see daylight, leaving the public blind to the depth of Britain’s involvement in abuses at home and atrocities abroad.

What began as a means of safeguarding military operations has been quietly subverted into one that manages perception itself. National security is now less about protecting the public from threats than about protecting politicians from the public. It shields them from international legal accountability, popular outrage, and the fundamental reckonings that democracy is meant to deliver. If Britain can be understood as an active participant in the Gaza genocide, then so too should its media, whose assent makes such crimes possible.