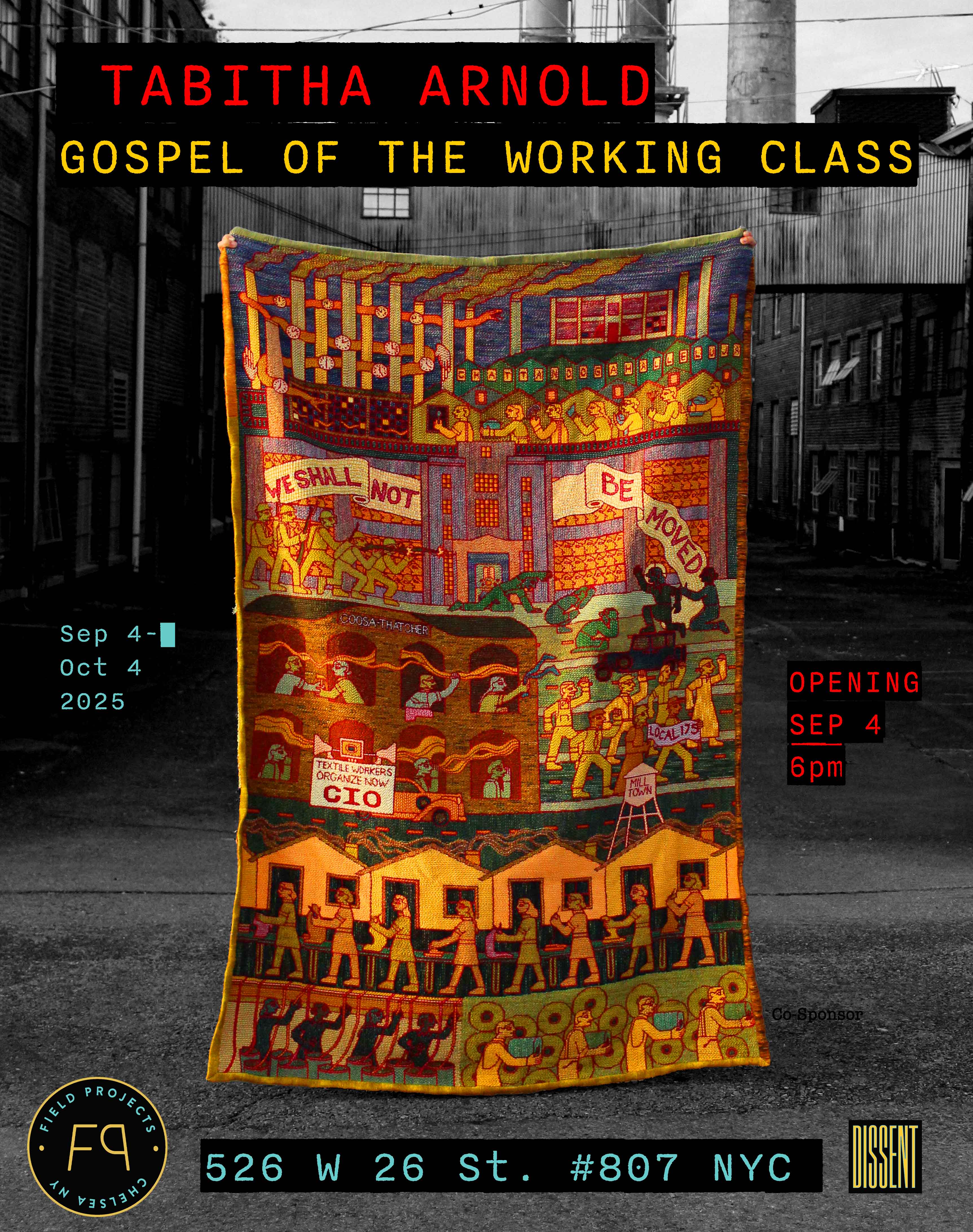

[NYC EVENT | September 4] Gospel of the Working Class

An exhibition of tapestries by Tabitha Arnold.

Join Dissent at Field Projects for the opening night of Gospel of the Working Class, a new exhibition by Tabitha Arnold, Dissent’s cover artist.

Gospel of the Working Class illuminates a hundred years of labor struggle in the South through a series of narrative tapestry banners. Inspired by a historic union victory by the United Auto Workers at Volkswagen Chattanooga in 2024, the show emphasizes the reactionary South as a site of revolutionary struggle, profoundly shaped by its history of labor militancy and working-class revolt. Arnold appropriates Bible Belt imagery from her childhood as symbols of class struggle, a nod to the deep tradition of spirituality interlinked with socialist organizing in East Tennessee. The tapestries rest on the same banner poles used at the annual Durham Miners’ Gala in England, transforming them into public artworks that can travel to union rallies and live with the working people whose struggles they commemorate.

Tabitha Arnold is a Chattanooga-born artist, socialist, and labor organizer. Her labor-intensive embroidered tapestries reflect coming of age during a wave of renewed union efforts in the United States. In 2019, Arnold joined an emerging cafe workers’ movement in Philadelphia, where she studied painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her experiences in the workplace and on the picket line informed her self-taught textile practice, which references political art movements like Soviet social realism and Palestinian liberation posters. After moving back to Chattanooga in 2022, Arnold began to depict the radical labor history of the south as a call for East Tennessee to return to its militant roots.

Where: Field Projects (526 W 26th St #807, New York, NY 10001)

When: Thursday, September 4, 6 p.m.