For New Orleanians like Black Panther community organizer Malik Rahim and author Sarah Fouts, the hurricane that struck the city 20 years ago marked a pivotal moment in America’s shift toward the political right.

filed inHistory

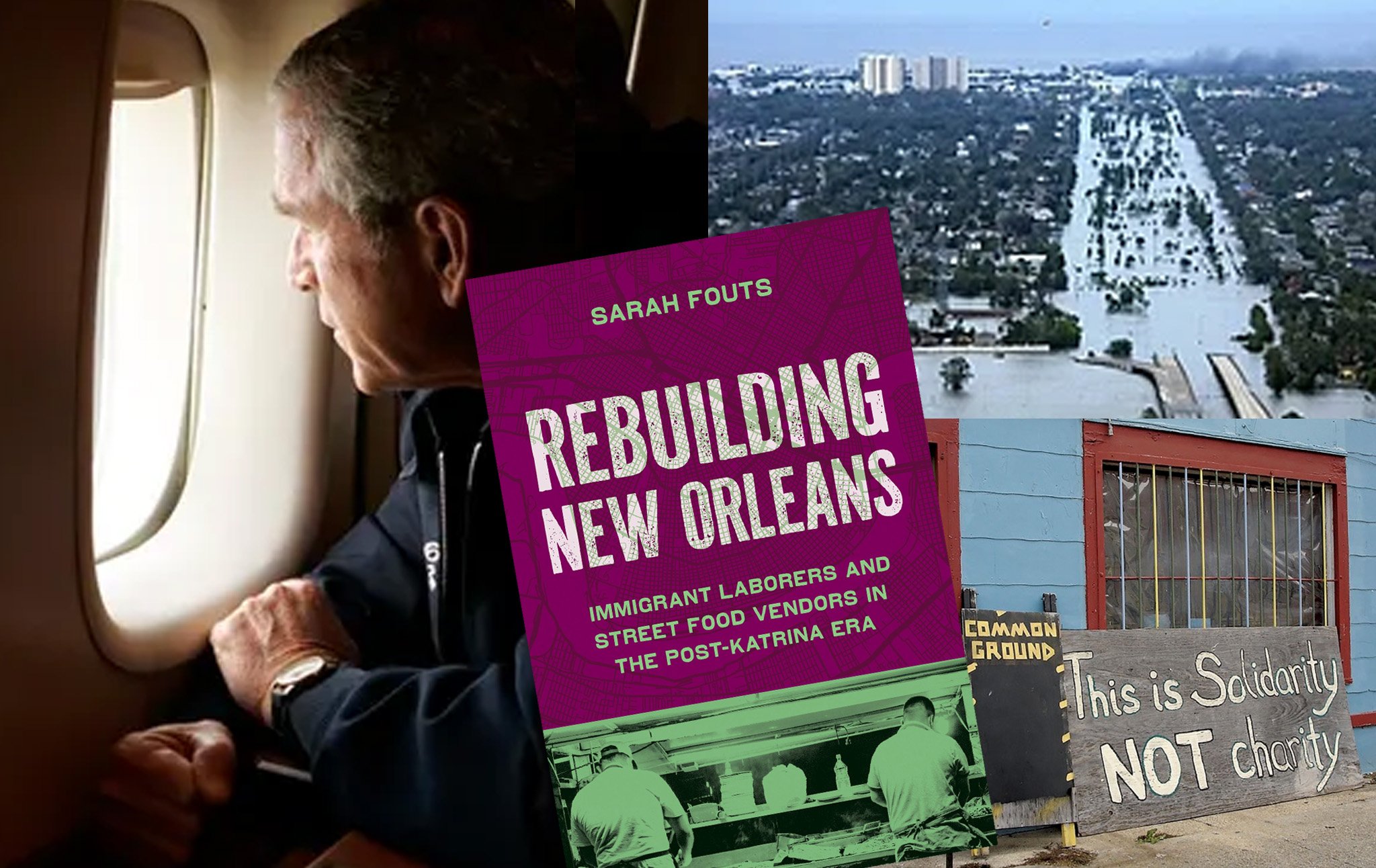

“It was a turning point to the right,” Malik Rahim says of Hurricane Katrina. “It was when the right saw they had the ability to create justice… If we had stood up for justice after Katrina, there may not have been a Jena.1 If there wouldn’t have been a Jena, then maybe there wouldn’t have been a Ferguson. All of it was the ripple effects of what did not happen after Katrina.” Rahim was one of the original founders of the New Orleans Black Panther Party in the early 1970s, helping to organize its “free breakfast program for children, political education classes, facilitation of free medical care, and neighborhood clean up and empowerment programs.” After Hurricane Katrina hit the city in 2005, countless Black residents were left stranded in a flooded city without federal or state assistance. Rahim took the organizing skills he had honed during his Panther days and founded Common Ground Relief, a radical, community-based mutual aid organizationoffering free health clinics, food and water distribution, home rebuilding, and legal support. Common Ground attracted legions of volunteers from outside the city and became a symbol of solidarity and self-determination. Nevertheless, Rahim sees the tragedy of Katrina as a critical “turning point to the right” because: Justice did not prevail. After any disaster, if you want to prevent that disaster from turning into a tragedy, justice has got to prevail. Corruption, racism, exploitation: these are the things that prevailed in this city. The story of Katrina, then, is a story of resilience by groups like Common Ground, but also one of defeat. The city was rebuilt, slowly, but it was a highly unequal and unjust recovery, with the worst burdens inflicted on the poorest residents. Both evacuation and return were stratified by race and class, and while the middle class and affluent actually experienced something of a renaissance in New Orleans in the years after Katrina, much of the social fabric of the city was permanently wiped out, never to return. “Katrina” has entered the American lexicon as a byword for government failure, tragic injustice, or just a terrible natural disaster. (See Richard Campanella’s “A Katrina Lexicon” for more on its usage.) It is worth remembering, 20 years on, just what this calamity meant to the people who went through it. No other major American city has ever suffered anything like Katrina. The population never fully recovered. There were 460,000 people in New Orleans in 2004, and less than half that the year after the storm. By 2008, half of the city’s pre-storm working poor, elderly, and disabled residents had not returned. Decades on, there are still only 360,000 people here. Even Chicago after the Great Fire and San Francisco after its 1906 earthquake did not experience such lasting decimation. And, of course, the collapse wasn’t equal across neighborhoods, with some predominantly Black areas like the Lower Ninth Ward losing nearly two-thirds of their population. Some tragedies were immediate. Others were long-term. Approximately 1,400 people died in the storm itself, the third-highest death toll from a hurricane in American history. In the aftermath, while some like Rahim were organizing relief efforts, white communities focused on keeping out Black storm refugees. ProPublica explains: Facing an influx of refugees, the residents of Algiers Point could have pulled together food, water and medical supplies for the flood victims. Instead, a group of white residents, convinced that crime would arrive with the human exodus, sought to seal off the area, blocking the roads in and out of the neighborhood by dragging lumber and downed trees into the streets. They stockpiled handguns, assault rifles, shotguns and at least one Uzi and began patrolling the streets in pickup trucks and SUVs. The newly formed militia, a loose band of about 15 to 30 residents, most of them men, all of them white, was looking for thieves, outlaws or, as one member put it, anyone who simply “didn't belong.” Rahim explains that in that period, “if you were African American, you’d better not get caught walking through Algiers Point to get to the evacuation station.” ProPublica has documented 11 shootings of Black residents by white vigilantes that occurred in the storm’s aftermath, which were never punished. That was just the beginning. As the city rebuilt, it did not rebuild with equal speed for all. As Sarah Fouts, professor at the University of Maryland and author of Rebuilding New Orleans, explains, much of what turned Katrina “from a disaster to a tragedy” (as Rahim said) was the way that lawmakers, city officials, and local business groups chose to use the opportunity to reinforce the city’s worst inequalities: What makes it so devastating was the kind of “disaster capitalism,” the racist policies, the exploitation of workers, paving the way for this new vision created not by the people but by the profit model… Initially 80 percent of the city is flooded, the population is out… The policies and actions that came immediately after exacerbated a lot of the damage that was already done just by the hurricane, like suspending federal policy (Davis-Bacon laws, OSHA laws), and facilitating the exploitation of labor. Failed policies like Road Home were devastating for the Black working and middle class, and catered toward people who lived in [wealthier, whiter] Lakeview instead of people who lived in the [more working class, Black] Lower Ninth Ward. New Orleans became an example of what Naomi Klein calls “the shock doctrine,” with politicians and wealthy business interests using a moment of crisis to force through sweeping policy changes that could never pass in a moment when the population was in a position to resist. The city was subjected to the most radical school privatization experiment in America, going from having 123 public schools to having only 4, with the rest being privately-operated charter schools. As Tulane University professor Celeste Lay told Current Affairs, when “Katrina flooded New Orleans, it didn't just destroy much of the city, it also destroyed the school system” and “some school reformers thought maybe that’s what needed to happen.” The state legislature transferred authority over the schools away from the school district. Lay says that while the charters focused relentlessly on test scores as measures of success, in the process, local democracy was essentially destroyed, with private entities rather than a traditional elected school board controlling every aspect of schooling. New Orleans went from having one of the highest percentages of Black public-school teachers in the nation to a teaching force that is much whiter and younger. This undemocratic recovery was not limited to schooling, but was characteristic of post-Katrina New Orleans as a whole. There was even, at one point, a plan to eliminate whole neighborhoods and never rebuild them. As Fouts explains, The planners were white folks making some of these big decisions and envisioning these plans. Some of the city council members were thinking about these new policies in ways that did not serve the working class Black communities that are so integral to the city. The jobs that came back [tended to be] tourism and service sector jobs, bars, restaurants, things like that. And even thinking about public transportation, people were displaced, pushed into the East, but there's no serviceable public transit that can reach that far away. So how are you trying to rebuild for the people who make the city? Fouts also cites the fact that the city’s public housing projects were shuttered and never reopened. The city demolished housing projects that hadn’t even suffered storm damage, eliminating thousands of affordable units at the height of a housing crisis: The destruction of all the public housing in the city was this complete turn that was intentionally aimed at poor, Black communities with nowhere to go. There was a huge impact of that, you still see the repercussions to this day. They rebuilt Section 8, mixed-income housing, but not enough to replace what they tore down. They tore down the Iberville Projects, I talk about [this] a lot in the book [Rebuilding New Orleans], thinking about the importance of that neighborhood for the Black community, and the vision that these developers had for this “Paris of the Caribbean,” this whitened vision of what the city should look like. But the story of post-Katrina New Orleans is not solely a story of exploitation of Black communities by white developers. Malik Rahim actually points to Common Ground as an inspiring example of cross-racial solidarity. “We had almost 20,000 volunteers come,” he says, “and almost 90 percent were white… it set a whole new precedent that had never happened, nowhere in the South.” “It broke the myth that all whites were racist,” he says, because “for a lot of people in our community, it was the first time they ever had direct contact with any white person.” Rahim says that the work of Common Ground shattered stereotypes about how “dangerous” and full of “looters” New Orleans was in the aftermath of Katrina. “Individuals that volunteered” were “in what was called some of the most ‘dangerous’ communities in the city, and there was never a person being robbed, raped, or killed… These are the things that [the media] refused to look at… They were saying that everybody that was stuck in the city were criminals.” Rahim says that many who made sacrifices to help were never given credit, and the media was never interested in the positive work being done by his group. He especially wished to single out leftist filmmaker Michael Moore for credit. Moore has “never gotten any type of recognition for what he did,” but “he sent staff here and purchased a boat for us… There wouldn’t have been a Common Ground to the degree that it exists, if it wouldn’t have been for Michael Moore.” Rahim believes that the rest of America should pay attention to the injustices of the Gulf region, because “I work under the premise that so goes the Gulf, so goes America. And so goes America, so goes life as we know it on this planet. It’s just that simple.” If the post-Katrina recovery had been different, if it had all embodied the solidaristic ethic that Common Ground possessed, New Orleans today would be a more just and equal city. But we would also have a model for how disaster recovery could be done equitably, without worsening the injustices that were present before the disaster. Rahim says Katrina was a turning point because it showed the opposite: that a disaster was an opportunity for exploitation by the right, rather than a moment for the people to come together and organize. 1: The Jena Six case was a widely criticized case of prosecutorial malpractice in which six Black teenagers in Jena, Louisiana, were initially charged with attempted murder for a school fight in December 2006, after several white teens had hung nooses from a tree.

Malik Rahim at Gwangi & Hollywood Community Center, 2025

The original Common Ground location, in a former corner grocery store