A brief history of our most rebellious musical genre, as seen through its DIY zines.

filed inMusic

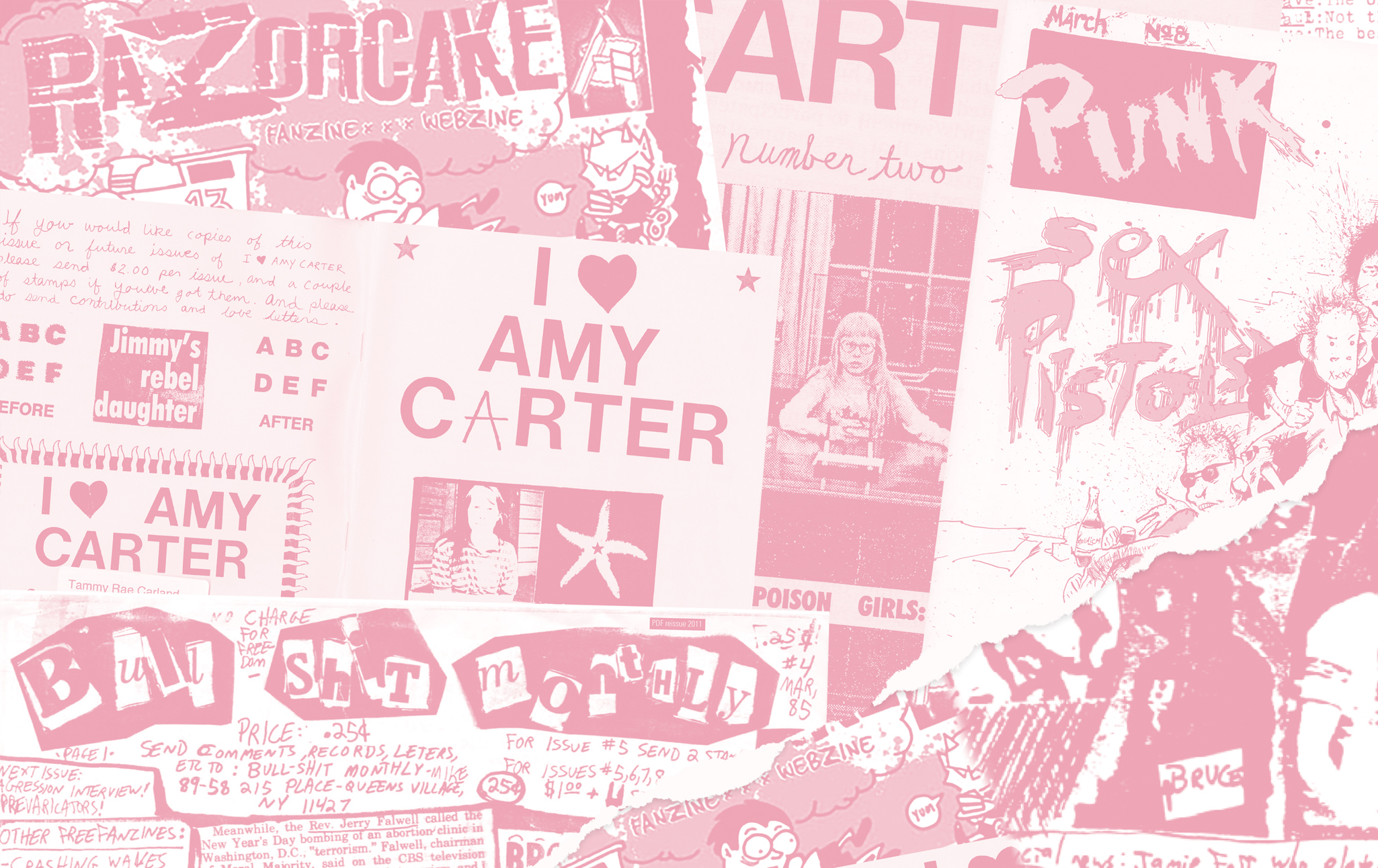

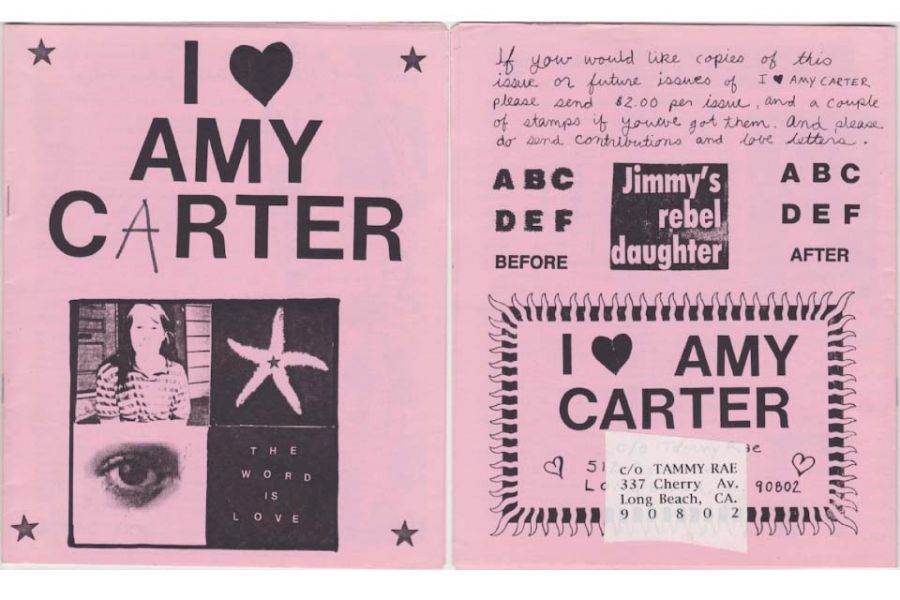

It’s July 26, 2024, and I’m at Elsewhere, a former warehouse turned music venue in Brooklyn, New York. My friend Beleth and I have come to see Snõõper, a punk band from Nashville. We’ve been friends since middle school, but have followed diverging paths. Beleth’s a true punk, a self-taught guitarist, bassist, and illustrator who puts up with barista work at our local Starbucks for the sake of devoting their life to their creative talents. As a transgender artist who found acceptance, community, and inspiration in Brooklyn’s queer punk scene, Beleth’s a natural fit for the culture. In contrast, I’m a strait-laced graduate student at the University of South Carolina, where I study twentieth century American popular culture. I’m researching the history of punk in New York City for my Ph.D. dissertation, and while I’m not afraid to profess my love for punk—its history of leftism and exhilarating music drew me to the culture—at this point I only knew about it secondhand, from the scholarship I was reading. So I reconnected with Beleth and asked her to take me to see Snõõper, who I’d read about in Creem, a publication that proclaims itself “America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine.” “Elsewhere is kind of bougie; you could go to a basement show for free,” Beleth told me. “You don’t need to be so concerned about being ‘punk’ or not. That’s not the point.” “I don’t think a pit’s going to form. The venue’s not that kind of place.” On this last point, Beleth was dead wrong. Taking the stage, Snõõper bombarded us with a wall of fuzzy, delightfully deafening guitar noise as frontwoman Blair Tramel began hopping in excitement, blurting the opening to “Company Car”: “I’ve got the keys to the company car / I’ve got my own so it’s kind of bizarre!” “Holy shit!” cried Beleth as we felt a mass of humanity swirl around and separate us. Guitarists Connor Cummins and Ian Teeple threw out riff after riff as drummer Cam Sarrett kept the beat racing at a breakneck pace. In a perfect visual metaphor for punk itself, bassist Happy Haugen stepped out onto the supportive hands of audience members, who held him up as he fingered chords: an awesome individual, supported by people dedicated to a collective culture and the creativity it fosters. Creativity abounds in Snõõper. The band’s quirks, like their matching tracksuits and use of large papier-mâché puppets—most notably their nine-foot tall green mosquito mascot—are so uniquely them. “[U]npredictable riffs and voltaic singing that strike just the right balance of delightful and detached[…] The total effect of Snõõper’s high-velocity songs is like clutching a plasma globe with both hands,” concludes a Pitchfork review of Super Snõõper, the band’s debut album. In “Pod,” my favorite track of theirs, Tramel’s chipper vocals are a thin cover for existential COVID–19 era angst: “Take a shot, take a shot / I got, got a question / Who sees, who sees / Society’s infection?” As I jumped along with Tramel and watched smiling punks slam against each other in an honest-to-goodness mosh pit, it was impossible not to love everything about the experience. As an older member of Generation Z born in 1999, my coming-of-age has been defined by the COVID–19 pandemic and two Donald Trump presidencies. (This sucks. I would not recommend it.) More recently, I’ve watched in horror as generative AI programs threaten to displace people from their jobs and do our thinking for us. In times like these, punk is both an affirmation and an intellectual reckoning. There’s a comfort in knowing that previous generations have also been disgusted with the state of the world, and a hope that we might learn from their successes and failures. By studying punk, I learn about a rich tradition of oppositional thinkers who, discontent with embracing the cookie-cutter lives and ideas sanctioned by mainstream society, constructed an alternative culture they could call their own. Since January of this year, I’ve been volunteering at ABC No Rio, a collectively run arts organization on New York City’s Lower East Side that hosts punk shows and fosters the culture. There, I’ve become part of a community of like-minded people who are righteously angry with the world and want to change it for the better. I archive zines—self-produced, small-circulation publications characterized by their irreverence and personality—in ABC No Rio’s Zine Library to help preserve this culture and make it accessible. Now, in presenting you with the history of punk in the United States, in all its perils and possibilities, I hope the culture can inspire you just as much as it’s inspired me. What exactly is “punk,” a concept that punks—by which I mean anyone actively engaged with punk culture—have hotly debated since its very inception? In a word, punk is rebellion. It’s a sensibility that prizes skepticism of, and revolt against, any form of authority and anything that might constitute a status quo. What exactly this “status quo” is depends on who you ask, as punk opposition has historically ranged from political protest—most often leftist, particularly anarchist, but sometimes right-wing too—to contrarianism and hedonism for their own sake. On the more politically coherent side, the Rock Against Reagan tours, put together by punks in the early 1980s, voiced opposition against “Reagan, Radiation, Racism, the Right, Repression, Registration [for military service], and Recession,” as described by organizer Jim Alias in the Spring 1982 issue of his zine I Wanna. In stark contrast, Legs McNeil, one of the very first self-identified punks, argues in his book Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk that “the great thing about punk was that it had no political agenda[…] It was also about doing anything that’s gonna offend a grown-up. Just being as offensive as possible.” While these examples are drawn from different periods, these divergent approaches to punk have long coexisted and clashed within the culture. Attempts to narrow the definition of punk hinge on rejecting others. The never-endingdebateover whether Green Day is “punk” is a case in point: the band undoubtedly emerged from punk culture, specifically from California’s vibrant Bay Area scene, but its immense popularity and openness to commercial success cast its cultural credentials into doubt. (It’s hard to be truly “punk” if you’re also collaborating with 7-Eleven to sell branded “Punk Bunny” Slurpees, as Green Day did this year.) Whatever comes to mind when you think of the word “punk,” whether it be blisteringly fast rock and roll, leather jackets, or sweaty mosh pits, it’s all part of a larger culture dedicated to the expression and embrace of dissent. Musically, punk takes the form of punk rock and its subgenre of hardcore, which both center around a loud, fast, and aggressive sound often described as stripped-down rock and roll. Vocals are often shouted, snarled, or sneered, backed by distorted electric guitars that punctuate songs with power chords and catchy riffs. Basses and drums typically stick to nimble and punchy rhythms to structure the music and maintain its sheer speed, especially for hardcore songs, which can surpass 300 beats per minute. Physically, punk manifested in local scenes. Across the United States’ suburbs and cities, punks formed communities, started bands, and booked shows in any venue they could find. Visually and textually, punk found tangible form in zines. Taken together, this is the stuff punk culture is made of, designed not just for consumption but also to encourage others to try their hand at it. To be punk is to create. This truism is embodied by the culture’s embrace of the do-it-yourself, or D.I.Y. ethic: a conviction that individuals should think and express themselves freely by creating their own culture on their own terms. Just like punk, the D.I.Y. ethic is a contested and multifaceted idea, intuited rather than spelled out. For instance, Ian MacKaye, frontman of influential punk bands Minor Threat and Fugazi, defines punk and the D.I.Y. ethic in terms of their freedom of expression, which in his view can only be realized when uninfluenced by a profit motive. As he says in an interview with Huck magazine in 2020, “My definition of punk is the free space. It’s an area in which new ideas can be presented without having to go through the filtration or perversion of profiteering. So, if we’re not worried about selling things, then we can actually think.” However, interpretations of D.I.Y. highly vary. For some punks, adhering to this ethic where music is concerned might involve only signing with independent record labels or entirely rejecting the idea that art is something to be profited from. But more generally, the D.I.Y. ethic is embodied in the desire and will to create things, rejecting traditions, rules, and conventions in doing so. The closest thing it has to a thesis statement is in the first issue of Sideburns, a British zine released in 1977. The reader, presented with diagrams of guitar chords, is told: “This is a chord. This is another. This is a third. Now form a band.” Punk began in New York City in the mid-1970s as a ragtag group of artists and misfits gathered around CBGB, a music club on the Lower East Side, and created their own culture. Inspired by hard rock acts like the Stooges, MC5, and the New York Dolls, these artists pioneered a stripped-down style of rock and roll in defiance of progressive rock (a genre that privileged technical skill in its characteristic guitar solos) and the dance-oriented rhythms of disco. They also took inspiration from the city’s queer underground and Andy Warhol-led art crowd, as their social circles overlapped. Rock critics like Lester Bangs and Dave Marsh of Creemused the word “punk”—up to this point a derogatory word for a disorderly youngster or prison slang for a victim of anal rape—to describe this new sound and cultural sensibility. Cartoonist John Holmstrom deepened this connection by foundingPunk magazine with Legs McNeil and Ged Dunn, Jr. in 1975, narrowing a loose collection of cultural features into a category that people could identify with, debate, and innovate upon. In defining “punk rock” in the zine’s third issue in 1976, Holmstrom outlined the greater sensibility of the culture: “any kid can pick up a guitar and become a rock ’n’ roll star, despite or because of his lack of ability, talent, intelligence, limitations, and/or potential and usually does so out of frustration, hostility, a lot of nerve, and a need for ego fulfillment.” Punk did not emerge in a vacuum. It was born from a combination of historical conditions and artistic drive. As an oppositional culture, it originated from a profound sense of discontent bred by the economic recession of 1973–1975 and the stultifying conformity of working- and middle-class life in America during the Nixon and Ford administrations. For instance, in the autobiographical song “Piss Factory,” Patti Smith laments the drudgery of working a low-wage, nine-to-five job: “It’s the monotony that’s got to me / Every afternoon like the last one / Every afternoon like a re-run.” By the end of the song, Smith’s narrator, like herself, resolves to escape to New York, where they can live their life anew. Richard Hell’s anthemic “Blank Generation” picked up where “Piss Factory” left off, as its lyrics wrestled with the liberation and disorientation of defining one’s existence on one’s own terms: “I belong to the blank generation, and / I can take it or leave it each time.” This ethos of self-reinvention—the seed of what would become known as the D.I.Y. ethic—empowered this first cohort of self-identified punks to live life as they saw fit, for better and for worse. On one hand, the culture’s contrarianism facilitated innovative forms of self-expression, manifested in its music and zines. While most American punks in the 1970s did not espouse a well-defined political agenda, their cultural experimentation affirmed to themselves and future generations that it was important to question and defy societal standards. On the other hand, early punks’ love of provoking mainstream society could descend into rank bigotry. At its crudest, this took the form of American punk culture’s flirtation with Nazi symbols, which was usually satirical. Bands like the Dead Boys wore swastikas for shock value rather than any actual alignment with fascism, and the lyrics of songs like the Dictators’ “Master Race Rock”—which range from “We’re the members of the master race / Got no tact, and we got no taste” to a shouted “Don’t forget to wipe your ass!”—are best described as juvenile sneering. But this was far from self-evident, especially to outside observers. Homophobia and racism were far more tangible, as some punks used their outrageousness as cover for genuine hatred and prejudice. In one infamous incident at CBGB in 1976, Dictators frontman Handsome Dick Manitoba heckled a performance by transgender artist Jayne County with homophobic slurs and staggered towards her, drunk. County responded by bashing Manitoba with her microphone stand in self-defense, sending him to the hospital. (In fairness, many scenesters sided with County, while Punk magazine cast its lot with Manitoba.) Casual racism plagued the 1970s New York scene as well, as evidenced by “The White Noise Supremacists,” an article published by rock critic Lester Bangs in The Village Voice in April 1979. Having hosted a party for the Punk magazine staff and “members of several of the hottest CBGB’s bands,” he recounts that “when I[…] put on soul records so everybody could dance—I began to hear this: ‘What’re you playing all that n—r disco shit for, Lester?’ ‘That’s not n—r disco shit,’ I snarled, ‘that’s Otis Redding, you assholes!’ But they didn’t want to hear about it.” The New York scene inspired punk’s emergence in Britain, where artists like the Sex Pistols and the Clash brought the culture mainstream media attention. This mid-1970s iteration of punk, often referred to as its “first wave,” ended towards the close of the decade. The Sex Pistols famously broke up in 1978 at the end of their first and only tour of the United States, leading record labels and the mainstream media to dismiss punk as a passing fad. As promoter Danny Fields recounts in Please Kill Me, “[w]hen the Sex Pistols broke up in San Francisco, it showed everyone that this punk thing wasn’t viable. That they were meant to self-destruct and so what’s the point in investing in any of them?” While acts like the Ramones secured modest record deals, punk rock was a hard sell and was overshadowed by the success of new wave, a catch-all pop-oriented genre influenced by punk. However, the culture did not disappear. Rather, these sea changes cleared the way for a new generation to out-punk their elders. Punk emerged anew in the late 1970s and early 1980s as younger people—teenagers, rather than the mostly twenty-somethings who populated the first wave—led the culture’s transition into “hardcore” punk. This iteration of the culture saw the music become faster, louder, and more aggressive, its makeshift sensibility formalized into the D.I.Y. ethic as a core value of the culture, and its politics become more coherent and outspoken. Whereas the first generation of punks in the U.S. were anti-status quo but not very politically motivated, the hardcore punks of the 1980s were resolute in their opposition to Ronald Reagan, who was practically the antichrist to them for his Cold War-mongering, economic deregulation, and slashing of welfare programs. And the hardcore punks were far more direct and blunt about the targets of their critique. Take, for instance, Reagan Youth, a New York hardcore band whose members named their group to satirically equate the president’s young supporters with the Hitler Youth of Nazi Germany. In the band’s namesake track, frontman Dave Insurgent sneers from the perspective of an imagined Reaganite: “We are the sons of Reagan… Heil! / We are the godforsaken… Heil! / The right is our religion / We’ll watch television / Tons of fun and brainwashed slime.” The likes of Reagan Youth were one of many hardcore bands that rose in revolt against the president, supported by grassroots scenes around the country that displaced New York as punk’s new cultural centers. This “punk rock world,” as historian Kevin Mattson describes it in We’re Not Here to Entertain: Punk Rock, Ronald Reagan, and the Real Culture War of 1980s America, was led by bands like Minor Threat, Bad Brains (Washington, D.C.), Black Flag (Los Angeles), and the Dead Kennedys (San Francisco), who, if not necessarily united in a formal political agenda, helped give voice to those angry with American injustice and energized punk culture as it expanded nationally and internationally. Bad Brains are particularly notable for being an all-Black punk band, a rarity in the culture, and for being one of hardcore’s most influential originators; some punks consider them to have created the subgenre. Zines like Tim Yohannan’sMaximum Rocknroll, which he founded in San Francisco to promote punk and leftism as two sides of the same coin,understood politics and culture as inseparable. As Yohannan, a 1960s hippie-turned-punk, argued in the zine’s first issue in 1982, “[i]f punk is to be a threat, different from society, then any so-called punk who flirts with racism and sexism, proudly displays ignorance, resorts to physical violence and is afraid of knowledge or political action, is not a threat at all, but has gone over to the enemy[…] It is the ideas behind the music, the dress, the ‘zines that are important, not the leather-clad bands and haircuts.” Many similarly understood that punk could challenge conservatism, capitalism, and war through direct action and artistic dissent. As part of the previously mentioned Rock Against Reagan tours, punks protested the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, staging “die-ins” criticizing nuclear war and chanting a slogan—“No war, no KKK, no fascist U.S.A.!”—that originated from a punk song: “Born to Die,” by MDC (Austin and San Francisco). The same slogan is still in rotation at protest marches today, with “no Trump” swapped in for “no war.” Punks in Washington, D.C. founded the activist collective Positive Force in 1985, which held benefit concerts for progressive causes, delivered meals to low-income elderly people, and organized “creative protests[...] done either alone or within other actions.” As Dead Kennedys frontman Jello Biafra declared in the 1981 song “Nazi Punks Fuck Off,” “Punk ain’t no religious cult / Punk means thinking for yourself!” Within punk communities, “thinking for yourself” often meant making, reading, and responding to zines. For an underground culture with scant coverage in the mainstream media, zines were vital. Constituting punk’s rich print culture, zines, because of their D.I.Y. nature and disconnect from considerations of profit, could be as irreverent and free thinking as the misfits who made them (not unlike Current Affairs). Typically xeroxed and stapled by hand, zines were distributed through the mail, at shows, and at whatever record stores would stock them; they were often sold for a few dollars or less, traded for other zines, or given away for free. Let’s look inside a few. Maximum Rocknroll (1982–2019), the most prominent punk zine in the 1980s, crammed as much tiny typewritten text into its cheap newsprint as its margins would allow, even as the monthly exceeded 100 pages by the end of the decade. Its (in)famous letter sections and editorials were punk’s public forums, hosting contentious discussions over what punk was, if punk was “dead,” and how one could best be a punk. Its scene reports, which related the goings-on of local scenes, underscore zines’ practical function as punk’s newspapers of record. Assembled by a large team of self-identified volunteer “shitworkers,” MRR was what D.I.Y. looked like when scaled up. Bullshit Monthly(1984–1991), the brainchild of Mike Bullshit, a mainstay of New York’s hardcore scene, was a far humbler publication. Bullshit started his zine at the age of 16 while attending hardcore matinees at CBGB, where he sold handwritten, xeroxed copies for 50 cents apiece. Packed to the gills with local punk news, band interviews, reader-submitted art, and stray ramblings, Bullshit Monthly was a typical scene zine: an irreverent work inseparable from the personality of its author. It also doubled as a personal manifesto. As a gay man in a predominantly heterosexual culture, Bullshit added a byline to later issues: “Proud to be gay owned and operated.” Later, the 1990s zine I (Heart) Amy Carter (1992–1994), created by Tammy Rae Carland during her graduate studies at the University of California, Irvine was also a labor of love. Named for President Jimmy Carter’s daughter Amy Carter, whom Carland had a girlhood crush on, the zine exuded rawness and vulnerability. As Carland stressed on the back of each issue: “a fanzine for the weak of heart. It’s about having butterflies in your belly and biceps in your brain. It’s about girl love + girl power + girl sex + and girl friends[…] It’s part National Inquirer part Dear Diary and part whatever the fuck I feel like.” Within its pages, Carland gushes over her love for queer punk bands and the riot grrrl movement (more on this later) and reflects upon her experiences as a lesbian, a feminist, and someone born into poverty. The zine, like countless other D.I.Y. efforts, prominently featured cut-and-pasted visuals and text from mainstream media publications, repurposed into artful collage. As the late writer Toni Morrison once said, “if there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Replace “book” with “zine” and you’ve found the driving force of every zinester who’s ever lived. Constructing a culture of rebellion was not without its challenges. As punk has historically existed as a largely white, male, middle-class, and heterosexual culture, this demographic skew has tended to narrow the scope of its politics and culture. This is not to say that punks of color, women, working-class people, and queer folks haven’t occupied central roles in the culture—they did and are featured in this history—but to emphasize that identity and class-based concerns could often go unheard or ignored by those who could not relate to or understand them. This is to say nothing of actual violence, which could be difficult to keep in check within a culture whose dancing (beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s) involved physically slamming against others in a mosh pit. (Though pits were typically peaceful, if rough around the edges, it’s all too easy for bad-faith actors to be violent within them.) Punk’s existence as an oppositional, defiant culture could also attract actual—not satirical—right-wing skinheads and neo-Nazis, generally outside agitators who plagued the national scene until mostly being kicked out of it by the early 1990s. These troublemakers worsened a growing trend of exclusionary violence in hardcore, which plagued scenes across the country. For instance, the New York hardcore scene—centered around CBGB—became dangerous as fights broke out in mosh pits and city streets. As Mike Bullshit recalled in 2012 on his personal blog: “[s]omeone would just get picked out and beaten the fuck up. I saw a horrifying ‘fag bash’ incident across the street. Just fucking bloody, and I was scared shitless.” When CBGB paused its hardcore matinees due to shows getting out of control, Bullshit started a new scene at ABC No Rio, a squatter tenement building home to an arts collective on New York’s Lower East Side. Beginning in December 1989, Bullshit bookedshows at the new venue with a firm policy prohibiting sexist, racist, or homophobic bands from performing. Punk’s status as an underground culture and its commitment to the D.I.Y. ethic were double-edged swords, both the culture’s best virtues and most difficult challenges. While punk has long been recognized by musicians, scholars, and music writers alike for its openness to amateurs, it could be impossible to find for people not already in the know. In the 1980s, if you didn’t already know a punk or have access to zines, you could have missed the culture entirely. The culture’s accessibility and sustainability were also tested by punks’ dedication to the D.I.Y. ethic, which afforded artists near-complete artistic autonomy for the price of burning out from fatigue. Most hardcore punks renounced the prospect of commercial success, though the loud and aggressive nature of their music meant they weren’t very marketable to begin with—for a time, anyway. In any case, their dedication to punk was a higher calling. For instance, hardcore tours, as recounted in memoirs like Henry Rollins’ Get in the Van and the 1984 documentary Another State of Mind, were often self-run, with artists booking and performing in makeshift venues in between crashing with fellow punks. There was very little money to be made this way, and tours were more likely to leave bands with deficits than profits. The commitment to D.I.Y. led punks to take on large amounts of work with little to no financial support, which was stressful for everyone involved and contributed to the culture’s volatility. Bands and zines, difficult for anyone to maintain for long, often ended up like the music they covered: loud, fast, and short. In the 1990s, punk faced further growing pains as the music broke into the mainstream and evolved into new genres. Two bands in particular—Nirvana (Seattle) and Green Day (Berkeley)—signed to major labels and brought punk unprecedented commercial success and attention. Hits like “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and “American Idiot” introduced listeners to punk’s sound and confrontational lyrics while also signaling the new musical directions the culture was going. Both songs made it onto the Billboard Top 100, with the formerpeaking at Number Six. Nirvana’s fusion of punk with metal influences helped birth grunge and alternative rock, while Green Day’s sound contributed to pop-punk, a subgenre that saw punk and hardcore move in a more pop-influenced, melodic direction. This commercial explosion, detailed in journalist Dan Ozzi’s book Sellout: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore, was an existential crisis for the culture. Many punks, especially anti-capitalist ones and those particularly committed to the ideals of D.I.Y., viewed this influx of money and mainstream media attention as the antithesis of everything the culture stood for. At the same time, it’s undeniable that this newfound popularity massively expanded the culture’s reach, especially for youngsters who didn’t have access to local scenes. Kurt Cobain, frontman of Nirvana, was at the center of all this. Devastated by depression and substance abuse, Cobain’s disillusionment with the trappings of fame was one of the factors that led him to take his own life. As he lamented in his suicide note: “All the warnings from the punk rock 101 courses over the years, since my first introduction to the, shall we say, ethics involved with independence and the embracement of your community has proven to be very true[…] it’s better to burn out than to fade away.” The gains punk culture made with its commercialization came with immense costs. The 1990s also saw identity-based movements emerge from within punk that challenged the culture’s white male heterosexual disposition. Riot grrrl, a feminist movement, emerged out of the Olympia, Washington scene to empower girls and women by encouraging them to start bands, make zines, and politically organize. Bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Sleater-Kinney (Olympia), alongside zines including Kathleen Hanna’sBikini Kill,Tobi Vail’sJigsaw, and Tammy Rae Carland’s I (Heart) Amy Carter spread word of the movement’s message of female empowerment and reclamation of punk. As Hanna argues in the first issue of riot grrrl, a zine she co-founded with Allison Wolfe, Molly Neuman, and Jen Smith (later of Bratmobile) in 1991, this new form of punk aimed to “Recognize empathy and vulnerability as positive forms of strength. Resist the internalization of capitalism[…] Don’t allow the world to make you into a bitter abusive asshole.” Homocore, later known as queercore, emerged in tandem with riot grrrl, lending queer punks greater visibility and championing their place within the culture and the world at large. As Matt Wobensmith outlined the aims of his Outpunk record label in his zine of the same name in its first 1992 issue: “(a) To provide images, role models, information, support, and strength to isolated queer kids who need it. (b) To give queer kids the tools to cope with and/or change their environments. (c) To give queer kids options I never had!” As works like Mimi Thi Nguyen’sEvolution of a Race Riotzine and James Spooner’s 2003 Afro-Punk documentary attest, the struggle for a more inclusive punk culture continues. As the world remains a profoundly fucked-up place, punk culture and its history compel us to confront and reflect upon its ills by getting involved in communities that empower and sustain us. Ever since the culture’s inception, punks and outside observers have repeatedly asked, “is punk dead?” My answer is a definitive no: it will live on as long as we continue to believe in the value and power of making culture on our own terms, and always question the status quo. The spirit of punk will only die if we allow it to, and we cannot let that happen. So please, dear reader, do yourself a favor by doing something for yourself today. Write something. Draw a doodle. Paint a picture. Make music. Volunteer. Get involved in political organizing. Seek out your local scene and find out what it’s all about. These individual acts cannot break the chains that capitalism binds us with on their own, but they’re a start. And last—but not least—be a punk. Hey! Ho! Let’s go!

image: SNÕÕPER

What is Punk?

The 1970s: The Birth of Punk

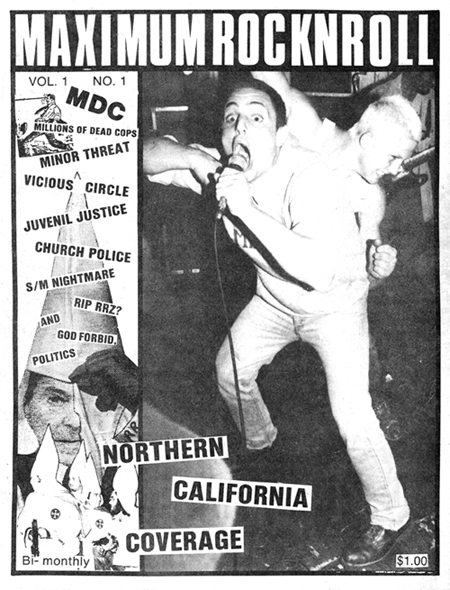

The 1980s: Punk Goes Hardcore

The 1990s: Punk Goes Mainstream