Recorded on: Jul 28, 2025

Description

In this week’s Frankly, Nate reflects on a moment of unexpected insight during a morning bike ride, which catalyzed a larger meditation on the modern human predicament. This episode explores the neuroscience of dopamine, and offers a reflection on the ways it plays into distraction, technology, and how we interact with the hyperstimulating world around us.

What is the “ghost of dopamine past,” and how does it shape not only our individual lives, but our collective economic and ecological behavior? Why does the urge to scroll on our phones override the deep calm of watching wildlife? And how might tactics like dopamine fasting or socialization help us rebalance our nervous systems in a culture engineered to constantly produce more?

Show Notes & Links to Learn More

02:40 – dopamine, neurotransmitters

03:05 – Peter Whybrow, Peter Whybrow TGS episode, American Mania: When More is Not Enough

03:15 – Wolfram Schultz, research about rewards + dopamine neurons in monkeys

06:20 – Parkinson’s disease

07:00 – Personality, Addiction, Dopamine: Insights from Parkinson’s Disease

12:30 – TGS with Audrey Tang, greyscale and digital wellbeing

13:22 – Dungeons and Dragons, Magic the Gathering

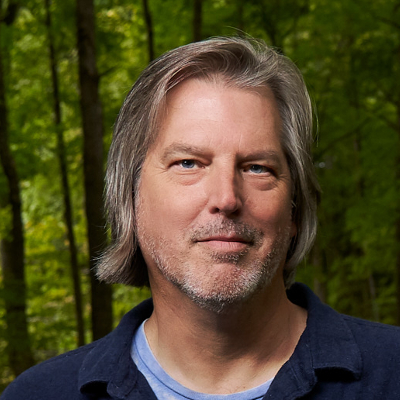

Nate Hagens

Nate Hagens is the Director of The Institute for the Study of Energy & Our Future (ISEOF) an organization focused on educating and preparing society for the coming cultural transition. Allied with leading ecologists, energy experts, politicians and systems thinkers ISEOF assembles road-maps and off-ramps for how human societies can adapt to lower throughput lifestyles.

Nate holds a Masters Degree in Finance with Honors from the University of Chicago and a Ph.D. in Natural Resources from the University of Vermont. He teaches an Honors course, Reality 101, at the University of Minnesota.

Related Articles

Spelling It Out

Yet if the value of the commons remains always partly mysterious to systems which can only deal with the legible, so too does their capacity for endurance and the strength which they give to those who live and work with them, and the process of enclosure is never quite as total as its promoters would like us to believe.

August 12, 2025