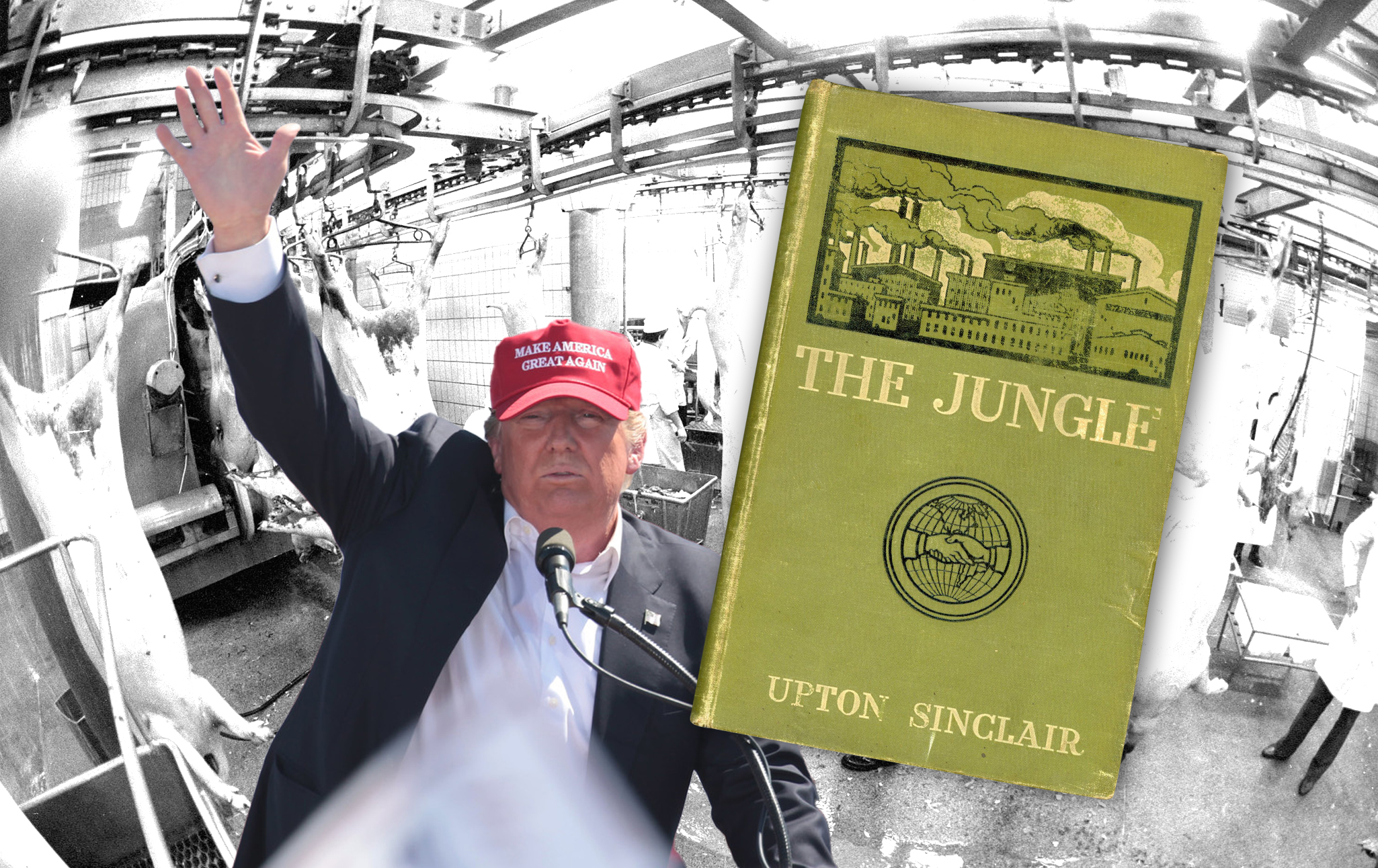

In 1905, Upton Sinclair documented the horrors workers in America’s slaughterhouses and meatpacking plants were forced to deal with. In 2025, Donald Trump is making them worse.

filed inLabor

In January, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released twinreports detailing some of the horrific health problems facing workers in the nation’s poultry and pork processing plants. The grim analyses showed that 81 percent of poultry workers were at high risk for musculoskeletal disorders, while in swine-processing plants, more than 42 percent of workers reported “moderate to severe upper extremity pain” in the last year. Naturally, the Trump administration did nothing to help them. Instead, just months after the reports’ release, they rolled back even more federal regulations. During the first Trump term, over a dozen poultry plants were issued waivers that greenlit them to speed up already-hectic production lines. Suddenly, plants were allowed to eviscerate 175 birds per minute—a 25 percent increase over the previous limit. Similar waivers were also given to several major pork processing plants during Biden’s presidency, allowing them to eviscerate pigs faster than the traditional limit of 1,106 heads per hour. This past March, the USDA officially announced those waivers would be extended posthaste. The department also began working to expand those more lenient line speed regulations to the entire industry. And this April, the USDA withdrew a proposal to create a new sampling program that would have tested for salmonella in raw chicken products and banned contaminated poultry. The reason for cranking up the line speeds, new Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins explained in one press release, was the Trump administration’s commitment “to ensuring our producers remain competitive on a global scale without being held back by unnecessary bureaucracy.”1 Others aren’t buying the spin—and they say the rollback of safety measures is a page torn from the darkest chapters of America’s industrial past. It’s a tale with troubling parallels to the industrial horrors and corporate corruption Upton Sinclair documented in his landmark novel The Jungle back in 1905. Some time has now passed since the USDA’s initial announcement. But when I recently emailed a department spokesperson, they confirmed that “rulemaking related to line speeds in pork and poultry slaughter and processing establishments is underway and is a top priority.” In what might come as a real shock, the Donald J. Trump administration appears to be putting the interests of meat industry shareholders over the safety of workers. Both the United Food and Commercial Workers and the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union quickly issued twinstatements condemning the proposed policy change earlier this year, pointing to the two reports released by the USDA as evidence that workers would be needlessly harmed. But while the USDA’s press release claimed “extensive research has confirmed no direct link between processing speeds and workplace injuries”—presumably referring to those January studies—an expert who spoke to Current Affairs stressed that this was only nominally true. It’s true that both reports failed to find a statistically significant correlation between line speed itself and workers’ risk of injury and musculoskeletal disorders (there’s the bait). But they identified piece rate—the volume of meat parts handled by each worker in a minute—as a significant factor determining the rates of health issues (and there’s the switch). Unless additional workers are brought on to the line—which employers are reluctant to do—then a faster line speed also means a higher piece rate. The researchers observed that as the speed workers had to process hogs “increased by 1 unit per minute, there was a 7% increase in odds of being at risk for [musculoskeletal disorders].” The study of poultry plants found a similar, statistically significant correlation. And that research just added to the already convincing body of evidence drawn from OSHA data that meatpacking and poultry plants are among the most dangerous places to work in the United States. Beyond the long-term risk of chronic disorders, a 2023 report found that an average of 27 workers per day suffer injuries severe enough to “cause an amputation, the loss of an eye, or an overnight stay in the hospital.” In exchange for this debilitating labor, slaughterers, meatpackers, and meat cutters and trimmers make less than $20 an hour on average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Industry insiders say that these facilities, due to their very design, are uniquely suited for disfigurement. “So what you need to understand about the meat and poultry industry is—except for the very beginning of the slaughter processing plant where the animal is eviscerated—everything is done by hand and by workers,” explains Debbie Berkowitz, a former senior policy advisor and chief of staff for OSHA now working as a fellow at the Kalmanovitz Initiative. “This is not a mechanized industry. This isn’t like the auto industry where people are working with machines.” Instead, workers—overwhelmingly immigrants and people of color—are expected to be as efficient, as consistent, and as fast as if they were battery or steam-powered. The meatpacking director for UFCW Local 663, Ruth Schultz, forthrightly told nonprofit agricultural news outlet Sentient that “the expectation that’s there above all is that workers behave like machines.” A 2019 Human Rights Watch report similarly described a shift in a meatpacking plant as “operating as components of a continually moving dissection machine.” It’s that repetitive, non-stop nature of work in these plants which, when work pace is too high, will inevitably cause disabling conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome and tendonitis. As previously noted, Trump’s USDA has made sure to stress that raising the rate plants can eviscerate animals won’t necessarily increase the risk of these injuries and health conditions. But that doesn’t mean they’ll add any safety guards either. “My guess is that the USDA won’t require companies to add workers to the line or make sure that each individual worker’s pace of work does not increase,” Berkowitz says. If companies take advantage of increases in line speed to try to economize on labor costs, that would mean increasing the speed that workers process animals, which the USDA studies did identify as a significant health risk. “Over a hundred years ago in The Jungle, Upton Sinclair made it clear that the breakneck line speeds were literally killing workers,” says Berkowitz. “And here we are, back in the same place.” First serialized in 1905 by the leftist weekly Appeal to Reason (think Current Affairs on newsprint), The Jungle was socialist muckraker Upton Sinclair’s attempt to write a naturalist novel a la Émile Zola that could draw the nation’s eyes to the horrors of life in Chicago’s meatpacking yards. If you didn’t have to read the book in sixth grade English, or opted to skim the CliffNotes, here’s your summary: the book follows Lithuanian immigrant Jurgis Rudkus. At the start of the novel, Jurgis moves to America with his fiancée and cousin because they believe “in that country, rich or poor, a man was free.” In relatively short order, he is left fully disabused of that notion through stints in meatpacking and fertilizer plants, paired with the untimely deaths of his wife and young children: Each one of these lesser industries was a separate little inferno, in its way as horrible as the killing beds, the source and fountain of them all. The workers in each of them had their own peculiar diseases. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the abolitionist novel that sold millions of copies while Southern politicians floated secession, served as Sinclair’s primary inspiration. He not-so-secretly hoped his book could do for the industrial wage slave what Stowe’s book had done for the agricultural slave a half-century prior. “I wished to frighten the country by a picture of what its industrial masters were doing to their victims; entirely by chance I had stumbled on another discovery—what they were doing to the meat-supply of the civilized world,” Sinclair explained in a 1906 article for Cosmopolitan magazine. And when his work was first compiled and published by Doubleday, Page & Company, he dedicated it “to the workingmen of America.” Although Sinclair may have dreamed too big—a decent novel unfortunately failed to kick off a socialist revolution—The Jungle did fly off the shelves. Winston Churchill, then “just” a member of the House of Commons, and celebrated author Jack London both wrote laudatory reviews. Due to the book’s phenomenal popularity, mere months passed between The Jungle’s publication and President Theodore Roosevelt signing the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the bill that established the Food and Drug Administration. But despite Sinclair’s urging, the president couldn’t be convinced to support similar legislation capable of properly addressing working conditions. Roosevelt would eventually write to Sinclair’s publisher that the socialist agitator ought to “let me run the country for a while.” Over a dozen years later, in the journalist’s tell-all The Brass Check, an embittered Sinclair would complain the public response to his earlier work had “left the wage-slaves in those huge brick packing-boxes exactly where they were before.” The Occupational Safety and Health Administration would not be created until 1970. Still, Sinclair’s tales of capitalist cruelty and criminal negligence, easily as vivid as Dante’s depiction of Hell, have served as a ready touchstone for horrific and unsanitary conditions for the last hundred and twenty years. The stomach-churning scenes he painted of poisoned rats being swept into meat grinders right along with tubercular pork and of men falling into vats, only to be sent “out to the world as Durham’s Pure Leaf Lard,”stayed with the American public, and with the nation’s elites. In 2017, Bloomberg reporter Peter Waldman wrote that OSHA inspection reports “read like Upton Sinclair, or even Dickens.” Late last year, whilst explaining there really isn’t all that much waste in the federal budget to begin with, one former Republican aide warned: “What are you going to cut out? The FDA’s food safety inspections? Well, I’m sure some of the big meat packers would like that, but you’d get a situation like Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle.” Reporting on America’s meatpacking industry would seem to suggest that The Jungle flopped, just another crankish socialist tract ignored by a non-receptive public. In reality, relative safety and decent wages only came to meatpacking when unions were there to claw them from the companies. Once the Reagan presidency rolled around and new plants being built in the South effectively de-unionized the industry, those improvements quickly proved transient. Workers were suddenly “exactly where they were before,” in Sinclair's words. This past November, an employee at Tyson Foods, the largest company in poultry processing, “struck himself in the clavicle” with the knife he was using and asphyxiated to death. At a Taylor Foods plant in Oregon, one woman described by management as a “good worker that follows instructions” had a finger amputated on the job. The company had failed to train her and seven other employees in the “Lockout/Tagout” system that should ensure equipment is fully turned off before maintenance. Lack of training was also responsible for a worker drowning in a hopper full of desiccated pig’s blood in Nebraska. Notes taken during the inspector’s interviews and workplace inspection acquired via a Freedom of Information Act request show that employees were trained “on the job” by simply shadowing senior workers. The inspector specifically noted that management was “aware of use [of a rod to] get product unstuck” and that workers were frequently forced to stand atop the hopper to clear blockages in the blood feed. But there were no written work rules for offloading or fall protection. The fine for such an easily preventable death? $33,554. And, exactly as Sinclair documented in 1905, complying with child labor laws is still as simple as taking forged documentation “from the little boy, and glancing at it, and then sending it to the office to be filed away.” Mar-Jac Poultry, a relatively small chicken processing company based out of the South, has repeatedly fallen afoul of national child labor laws over the last couple years. In 2023, a 16-year-old kid was killed whilst cleaning a deboning machine at the company’s Hattiesburg plant. The very next year, a federal investigator found several minors working in Mar-Jac’s Alabama location under fake names and with fake IDs. The company recently came to an agreement with the Department of Labor out of court for that second case, agreeing to pay $385,000 in penalties and take concrete steps to avoid hiring children in the future. But “ if a company somehow didn’t put the word out unofficially that they would look the other way if kids came in, kids wouldn’t come there,” Berkowitz told me. “Somebody’s gotta drive them there. This is not your local grocery store that you can walk to.” She specifically pointed to horrifying testimony in the DOL’s case against Fayette Janitorial Service that children as young as 13 hired to clean an Iowa pork processing plant had come to work wearing “pink and purply sparkly backpacks.” Even though civil servants at OSHA, the Department of Labor, and the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) are likely just as dedicated as ever to keeping American consumers and workers safe, funding for the agencies, as well as the fines they can issue, are plainly insufficient today. Unfortunately, it’s also increasingly evident that under current leadership federal agencies supposedly tasked with keeping workers safe and food poison-free will instead be concerned with, “ensuring our producers remain competitive,” in the words of ag secretary Rollins. Paula Soldner, chair of the National Joint Council of Food Inspection Locals, said that over the decades she worked for the FSIS before her recent retirement, the agency went from inspecting food safety to supervising companies’ inspectors. “When regulations changed for poultry and hog slaughter, there was a reduced number of inspectors at these facilities,” she told Current Affairs. “At that time, company employees were trained to perform the cuts and duties that the inspectors previously performed. Now, the inspector merely observes what plants’ employees do.” In other words, some meatpacking companies are now being inspected primarily by their own employees—a clear conflict of interest—with only a final inspection being performed by a government worker. The FSIS has also long suffered from a lack of food inspectors, a problem certainly not aided by DOGE cuts to the federal workforce, or by the nation’s food industry being far more geographically dispersed than it was in 1906. At the time Sinclair wrote The Jungle, the “Beef Trust”—a price-fixing conspiracy by the five largest meatpacking companies and the railroads that was deeply enmeshed with the Chicago political machine—could only have existed in the Windy City. The Union Stock Yards were the beating, bloody heart of the American meat industry, bringing in tourists and schoolkids from across the country. Millions of pigs and cows—and, according to Sinclair, horses—had their necks cut in Chicago slaughterhouses every year. Over the course of the 20th century, meatpacking operations spread into the South and more rural communities as a result of the neverending search for cheaper land and labor. But today, the deeds to those new operations have once again been snatched up by just a few sets of hands. One report by the USDA’s Economic Research Service last year detailed a “striking change” in meatpacking over the last 40 years. In 1980, the largest four companies in beef and pork packing controlled just over a third of their respective markets. According to the most recent data, the largest four pork companies now buy fully two-thirds of all hogs, while the largest four beef companies control 85 percent of all steers and heifers. Austin Frerick, who detailed corporate concentration in agriculture in his fascinating exposé Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry, told Current Affairs that he chose the book’s title carefully. “ My book is called Barons and that’s intentional, like I’m playing off robber barons,” he says. “I’m harkening back to a previous moment in American history and part of that is to show people we’ve been here before, we know what to do. And The Jungle is such a good opportunity to do that because it’s one of the best examples in American history of, here is a reformer-activist-writer who wrote a book, started a conversation, something was done in response to it. Policy choices were made and we decided as a society, in response to that book, to take an exploitative, low wage job and make it a solid middle-class living” during the era of high unionization pre-Reagan. An expert on agricultural and antitrust policy, Frerick worked for the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the Open Markets Institute before becoming a fellow of the Thurman Arnold Project at Yale University. His book details the paths to power taken by the individuals who dominate modern agriculture, from the Hansen family’s use of “concentrated animal feeding operations” to dominate the pork industry to the Reiters’ apparent circumvention of labor law in berry supply chains. The introduction to Barons explains that “we are living in a parallel moment when a few titans have the power to shape industries.” In The Jungle, a socialist character describes the Beef Trust as “a gigantic combination of capital, which had crushed all opposition, and overthrown the laws of the land, and was preying upon the people.” Frerick says he believes the present situation might be even more dire, because no one has sufficient political will to challenge the modern barons: We just went through a Democrat president where nothing happened, you know what I mean? How many stories did you see of a 12-year-old working in slaughterhouses and nothing changed? What consequences did the industry face? Oh, they paid a little fine, a slap on the wrist. Meanwhile, JBS just listed on the stock exchange. They’re the largest donor of the Trump [inauguration]. I mean, it’s a feeding frenzy. A Brazilian company, JBS Foods is the world’s largest meat producer and now one of the top beef packers in the United States following a staggering series of mergers and acquisitions. One of the company’s subsidiaries donated $5 million to Trump’s inauguration fund nine days before over a dozen senators, including Bernie Sanders, sent a letter to then-SEC chair Gary Gensler asking for additional scrutiny on the company’s proposed IPO. The senators singled out JBS’ “track record of corruption, human rights abuses, monopolization of the meatpacking market, as well as environmental risks.” In Brazil, JBS was a key actor in the “Operation Car Wash” investigation that toppled the Workers’ Party government and set the stage for Bolsonaro. The investigation exposed that the company had paid many millions of dollars in bribes to almost 2,000 Brazilian politicians; JBS was fined a whopping $3.16 billion by the Brazilian government in 2017 as a result. More recently, the company has also faced criticism from organizations like Greenpeace over its role in the deforestation of the Amazon. While there is presently no evidence JBS is engaging in illegal corruption in the United States, Frerick still used the company as an example of how politically connected the meatpacking industry is now. “ I think it says something when two of the three last Democrat presidents are very strongly tied into the meat industry,” he says. “Bill Clinton and Tyson’s, and then Joe Biden, the Delmarva chicken industry.” Clinton was close with Donald Tyson early in his political career and, once elected, faced allegations of favoritism towards the company “Don Tyson” had led. Biden voted against several amendments and bills opposing further consolidation in agriculture during his time in the Senate, a pattern some have attributed to the importance of the poultry industry on the Delmarva peninsula. It is those political connections, and the resulting ability of meatpacking plants to call up the White House and ask to stay open during a pandemic, that ensure labor remains cheap and disposable, and that plants remain extremely profitable for their owners. Sinclair’s description of the Beef Trust’s logic still rings true: “What they wanted from a hog was all the profits that could be got out of him; and that was what they wanted from the workingman, and also that was what they wanted from the public.” When a modern industry is as consolidated as meatpacking has become, it also becomes more difficult for organized labor to get a foothold, much less help govern a market and push for meaningful workplace safety measures. Long-time observers of the industry say they’ve watched this mass-monopolization in real time. “When I was at the AFL-CIO running a health and safety program that worked with poultry workers in the ’80s, there were a lot of different individual, smaller companies,” Berkowitz recounted. “You could really work as a union, get these individual companies with three or four plants to put in safety programs to reduce the incident of musculoskeletal disorders and amputations. But that sort of all fell by the wayside as these companies became enormously powerful.” Between 1953 and 2024, the unionization rate in meatpacking fell from 90 percent to just 13. Berkowitz says that for decades meatpacking companies have purposefully hired vulnerable workers, like recent immigrants and refugees, because members of those groups would be scared of causing any trouble for the company. Then, after the first Trump administration made it harder to hire immigrants, the companies “ended up having a blind eye to clearly young kids walking in their plants,” she posits. It’s this potent combination of drastic deunionization and purposefully preying on vulnerable populations that has allowed big meatpackers to keep wages low, conditions poor, and profits high. “Any change in the American food system has to be centered on labor,” Frerick stated. Jack London wrote well over a hundred years ago that The Jungle “is essentially a book of to-day.” It is a book of today too. The most pressing issue in 2025, as much as in 1905, is that oligopoly has gone unchecked. Without tales of rat droppings in our breakfast sausage to turn the public’s stomach, the attempts of organizations like Human Rights Watch to shine a light on the horrific pain and suffering caused by the meat industry have consistently proved as ineffective as Sinclair’s novel-writing attempt did. The American public might still gasp at lurid tales of children being gruesomely killed in Mississippi poultry plants, but conservative politicians have not once paused their efforts to loosen child labor laws. Until either the labor movement or daring government action checks the meat packing companies, we will not be able to leave The Jungle behind. 1: One expert isn’t even sure that increased line speeds would increase poultry companies' profits in the short term, though. Bridget Diana, a PhD candidate in the University of Massachusetts Amherst economics department, began studying the issue after hearing farmers back home complain that federal policies made it impossible to compete with big firms. Her research paints a more complicated picture: “While firms push for these deregulatory measures due to the intense and often chaotic nature of competition, they ultimately intensify the very competition that undermines their profits,” she writes. But when companies as big as Tyson and JBS say “jump…”