At President Donald Trump’s second inauguration, the ceremony saw the president-elect wreathed by billionaire tech CEOs including Apple’s Tim Cook, Google’s Sundar Pichai, Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg, Tesla’s Elon Musk, and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. The effect was similar to that of Big Tech’s 2016 pilgrimage to Trump Tower after the president’s first victory, when platform CEOs performed the usual ingratiating rituals expected of an incoming president.

But since January, the tech giants have found themselves under mounting pressure, partially due to the president’s notoriously mercurial nature but also because of litigation begun in his first term. While Musk’s dramatic fallout with Trump has gotten the most media attention, major tech players including Google, Apple, and Meta are facing serious antitrust challenges from the administration.

Here’s a rundown of the major legal battles that Big Tech is currently embroiled in and what might come of them.

Unappealing

Under the most pressure is Google parent company, Alphabet, which has been in the teeth of antitrust lawsuits for years now and is presently zero for two. As I’ve previouslydiscussed in Jacobin, the company lost its search monopoly trial last year and was then found guilty of monopolization last April over the dominance of its online advertising technology monopoly.

The legal process is now in the “remedy” stage of determining corrective measures. Federal judges are weighing how much to regulate or break up Google’s search monopoly in the first case, and its ad tech monopoly in the second. Measures range from the less severe, like terminating Google’s $26 billion annual payment to Apple to keep its search engine in the default position on the company’s smartphone browser, to the more dramatic, including forcing a breakup.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) has argued for a partial breakup in the former proceeding, proposing the company be forced to sell off its Chrome browser — an important move, as the browser facilitates its profiling of users and forms the basis of the Chrome operating system used on Chromebook computers. But the DOJ has also requested that the judge require that Google share data on its search engine with competitors in order to undo some of the inherent advantages that incumbent firms enjoy in network-based markets.

The remedy ruling for the search case is expected by next month, while the remedy proceedings for the ad tech case are expected in the fall. Google plans to appeal both verdicts but must await the rulings before filing. That means the tech behemoth will remain in monopoly court processes for years to come — but at least it has some company among its platform peers.

Meta Male

Mark Zuckerberg is somewhat notorious for shifting his views, persona, and corporate mission. He based his original Facebook platform on actual Ivy League freshman facebooks, bought up a number of competing apps like Instagram and WhatsApp, then changed the name of the resulting gigantic company to Meta when it briefly appeared that an immersive online world would become the next big tech bubble. Unfortunately, “the Metaverse” turned out to be an enormous bomb that the company is considered to have wasted tens of billions building out.

Then when Trump was reelected, the company made strenuous efforts to get in his good graces. That has involved heavy lobbying, including three personal visits by Zuckerberg to Trump’s White House, and the paring back of most of the company’s fact-checking efforts. The company also moved to settle Trump’s personal lawsuit against the company for suspending his accounts after the January 6 Capitol riot. The settlement saw the company pay Trump $25 million.

But Zuckerberg himself also pivoted away from his formerly liberal-friendly tech-wonk identity to adopt a contrived macho persona. This transformation included his appearance on The Joe Rogan Show during which the Meta CEO shared he had long felt that “a lot of our society has become . . . kind of like, neutered, or like, emasculated.” Industry observers widely interpreted the abrupt transition as an attempt to earn credit among the tech bro-sphere and with the Trump administration.

These efforts have not succeeded in getting rid of Meta’s legal troubles. The long-running Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigation of Meta’s purchase of its largest competitor, Instagram, went to trial this year. The complaint was filed during Trump’s first term and then refiled as an amended complaint under Joe Biden after it was thrown out of court for inadequate evidence.

As often happens in these cases, a good deal of the argument is what constitutes the relevant market, with the FTC claiming Meta dominates rivals like Snapchat and X in the market for connecting people socially, and Meta claiming it competes in a much larger online-video sector that includes YouTube and TikTok. By the FTC’s narrower market definition, Meta has a market share above 80 percent based on the time users spend on its applications.

And as with other tech trials, the fact that the business models are ad-based and the applications are free to use means the company has never raised user prices, which is a more conservative legal standard for proving monopoly. The FTC claims the company has in fact raised the “quality-adjusted price” by putting more ads in the apps and abjectly disregarding user privacy.

Like in previous cases of tech litigation, a number of incriminating emails have come to light in the trial. Prior to the Instagram acquisition in 2012, Zuckerberg himself wrote in an internal email that the new app could be “very disruptive” to the then fast-growing Facebook. A breakup today would be brutal for Meta, which gets about half of its revenue from ads on Instagram. And whereas the legacy Facebook app is in decline, Meta is growing among young people. Here again, the company’s prospects are endangered as it is also being sued by the FTC and a coalition of states over harmful impacts of the app on young people, especially young women and girls.

Far From the Tree

Apple is one of the companies with the most to lose from Trump’s trade war. The $3-trillion behemoth’s profit center remains the iPhone, its iconic flagship product and still the heart of the company’s cash flow. The company’s personal electronics products were at first included, then excluded, from the drastic tariffs on Chinese exports.

When the company indicated to shareholders it would shift production of iPhone models destined for US markets to India to avoid the shifting tariffs on China, Trump threatened in an online post that a 25 percent duty would be imposed on any Apple device not made in the United States — despite estimates that such a shift would take years and yield phones with sharply higher prices. Whether any such duty will be imposed on Apple devices is anyone’s guess under the erratic Trump administration, especially bearing in mind that its consumer electronics were exempted from tariffs this spring and during the president’s first term.

The company’s other main headache surrounds its App Store. As I’ve previously covered for this publication, Apple maintains a tight grip on its app marketplace, charging a hefty 30 percent commission on sales of apps and barring application makers from offering users a means to avoid that fee, such as by linking to their own websites. Years of litigation, most famously led by Epic Games, the maker of the hit video game Fortnite, claimed Apple abused monopolistic power with its exorbitant fee structure and other requirements. A federal judge ruled in 2021 that the company had to allow developers to offer other means of paying outside the store.

While waiting for its appeal, Apple followed the letter of the ruling by allowing outside payments to app makers but also began charging a new, separate 27 percent fee for using alternative payment methods. Last month, a federal judge found that Apple “willfully chose not to comply” with the injunction. The unusually stern language of the ruling is thought to have encouraged similar cases before the European Commission, which in April fined Apple half a billion dollars for its App Store policies and threatened yet larger fines if the company didn’t allow outside app purchases.

Besides these cases, Apple is engaged in various other running legal battles, like one with the state of Texas over implementing requirements that app stores verify a user’s age before allowing them to download apps (and if the user is a minor, their account must be tied to an adult’s to approve downloads). The company even went to the lengths of having Cook call Texas governor Greg Abbott to request a veto, although the measure passed the state legislature by veto-proof majorities. The likely loss of Google’s $20 billion-plus per year for default search-engine status, and Apple’s perceived lagging in the AI race, add to the headaches.

Amazon Grovels

Amazon has struggled to navigate the chaotic waters of the new administration as well. Billionaire Jeff Bezos gave $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee and famously stood behind him for the ceremony. He had his first run-in with the administration in April, when it was announced that Amazon was considering displaying product listings along with the price increment added by tariffs from Trump’s trade war. (This was contemplated for Haul, its ultra-low-price Temu-competing unit, and not for the main Amazon site as has sometimes been reported.) The news of the company considering this move led to a harsh response from the administration, calling the (never-implemented) idea “a hostile and political action by Amazon.” Bezos assuaged Trump with a personal phone call hours later, quickly smoothing over the oligarchic dustup.

A preceding episode involving Bezos’s control of the Washington Post is arguably even more embarrassing. After years of reliably endorsing candidates in the style of the national press, the Post had its planned 2024 endorsement of Kamala Harris abruptly pulled, even as other editorials endorsing other candidates ran without issue. Bezos justified his actions in a blog post amusingly titled, “The hard truth: Americans don’t trust the news media.”

While plainly admitting he appeared to have frequent conflicts of interest with his journalism property, from his need for NASA to buy his Blue Origin rocket services to his interest in Amazon Web Services being a Pentagon cloud provider, Bezos indicated that he now considered it inappropriate for his paper to endorse presidential candidates. The decision led to the loss of a quarter-million readers, reportedly 10 percent of the paper’s readership, who killed their subscriptions shortly after the decision.

But perhaps the most undignified display of obeisance by Bezos’s empire was Amazon wildly overpaying for the rights for a documentary about Trump’s wife, Melania. The company paid $40 million for the rights for the film, which will follow her supposed day-to-day White House responsibilities.

On top of turbulent relations with the president, Amazon is dealing with its own antitrust confrontations, though less serious than those facing Google and Apple. The FTC and a coalition of US states sued the company in 2023 over a number of trade practices, most prominently “Project Nessie,” an algorithm that automatically searched the web for product prices on other retail websites and adjusted Amazon’s listed price points downward to match them.

Given Amazon’s gigantic weight in online retail, the FTC has a decent case that the practice (now claimed to be terminated) amounts to price-fixing. That suit also covers the platform’s policies on independent sellers, when requiring them not to offer products more cheaply on other websites, and adding so many fees and costs that the company now collects almost half the dollar amount for third-party sales on the platform.

The FTC also has a legal complaint against the company over its exploitation of “dark patterns,” practices used by online entities to exploit or manipulate consumers into purchases or other actions. Their complaint alleges that while signing up for Amazon’s quick-shipping and streaming Prime service takes one or two clicks, quitting requires a “four-page, six-click, fifteen-option cancellation process.” About 72 percent of US households pay for Amazon Prime. The FTC cases are still in litigation.

Meanwhile Germany’s Federal Cartel Office is assessing Amazon’s practices regarding its independent seller market, including its ability to more prominently feature low-priced offerings and demote, or even delete from visibility, higher-priced offers. The company has been designated as important for competition across international borders, bringing it more scrutiny, and a negative assessment by the German regulator would likely encourage sanctions by the main European regulator.

The $2-trillion company will be paying millions in attorney fees for some time to come, but the threat of binding settlements has the greater price tag.

Barred Windows

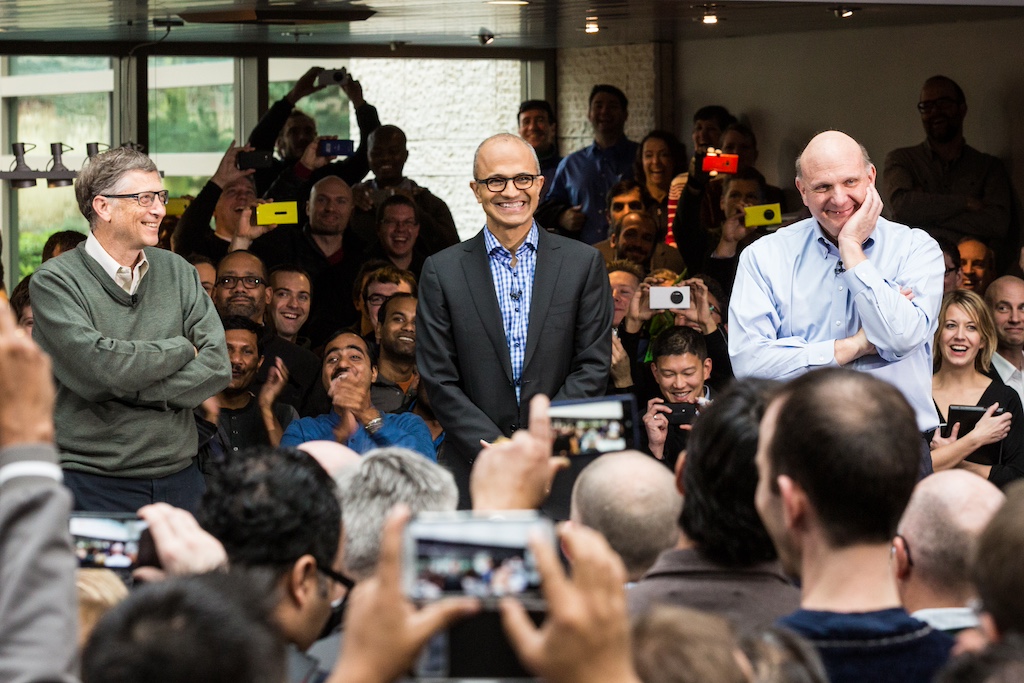

For Microsoft, the legal travails of its rivals has probably been enjoyable to watch. The company of course was itself the first major platform monopolist to be brought to trial for its power-mongering in various online sectors back in the 1990s, and while it skated breakup on appeal, its legal adjudication as a monopolist was never overturned. It had to deal with bothersome regulations for some years after the verdict — even if they were only sporadically enforced — but it never had to confront its nightmare scenario of a breakup.

But even this grizzled veteran isn’t fully avoiding antitrust charges. In 2024, the Biden administration opened antitrust probes of Microsoft and its valuation-boosting asset, OpenAI (including its ChatGPT platform), as well as AI chipmaker Nvidia, to explore if they were controlling or manipulating the emerging AI market. Microsoft, having learned its lessons around monopolization, has attempted to evade competition scrutiny by sometimes forgoing outright acquisition of takeover targets and instead using complex arrangements where it hires much of a company’s staff and licenses its technology.

A major focus of the FTC probe is bundling — specifically, whether Microsoft’s bundling of OpenAI’s products into its email and other Office applications violates fair competition rules. This is ironic because it was Microsoft’s insistence on bundling its lousy web browser with its then ubiquitous Windows operating system updates that got it into legal trouble in the 1990s. In both instances, Microsoft has required users of its main products to use its offering for a more cutting-edge sector — web browsers in the 1990s, AI applications in the 2020s.

And indeed, this year it was reported that OpenAI is in a serious struggle with Microsoft over their complex business relationship. Microsoft invested $13.7 billion in OpenAI in exchange for 49 percent of the entity’s future profits, exclusive use of Microsoft’s cloud services, and preferential access to new AI technologies developed by OpenAI. But the agreement is now disputed by the companies, including the terms under which OpenAI was planned become a separate company, with tensions high enough that the AI startup discussed a “nuclear option” — accusing Microsoft of anticompetitive behavior during their partnership, which would plunge the software giant further into more antitrust headaches.

Antitrust battles aside, the $3 trillion monopolist appears to have been complicit in far graver crimes. In an unsigned blog post, the company recently admitted it was selling AI services to Israel but claimed that an “internal review” had found “no evidence” that the company’s services were used to target people in Israel’s ethnic cleansing of the Gaza Strip.

However, Microsoft concedes that after the October 7 Hamas attacks, it “provided limited emergency support” to Israel to aid in the rescue of Israeli hostages, without specifying precisely what increased support this refers to. The Associated Press (AP) has filled that gap, finding in an extensive report that after the Hamas-led attack, Israel’s “use of Microsoft and OpenAI skyrocketed,” with usage at one point rising by some two hundred times the pre–October 7 level. The AP also cites an unnamed Israeli intelligence officer claiming AI has been used in all targetings in the past three years.

The genocide against Gaza has since led to firings of Microsoft workers who objected to the company’s involvement, including two fired for protesting during the company’s fiftieth-anniversary celebration. Employees were ejected from a talk by company CEO Satya Nadella for wearing shirts reading “Does Our Code Kill Kids, Satya?” (Google, for its part, fired twenty-eight employees after they staged a sit-in protesting the company’s own large contracts with the Israeli Ministry of Defense.) But it is hard to imagine Microsoft will be legally held to account for this behavior anytime soon.

One Hands Washes the Other

Even as the platforms face significant legal challenges, they remain in some of the greatest positions of power in the world and have plenty of tools for resisting the law. Most recently, the biggest tech companies have been trying to evade scrutiny by marking more of their (likely incriminating) internal conversations as “privileged” and thus inaccessible to the court process under attorney-client privilege. Amazon, for example, has been accused by the FTC in its Prime case of “systematic abuse of privilege,” noting that after FTC inquiries the company withdrew 92 percent of its privilege claims, producing about 70,000 pages of additional documents.

Google is also now notorious for excess labeling of conversations as privileged (or CC’ing legal staff on emails, which has similar effects), to the extent that the presiding judges in its cases have concluded it was a deliberate choice to hinder the legal process. The company’s internal messaging tool’s default setting was reset to “off the record,” where the chat log was automatically deleted the following day. The practice was pervasive enough that the presiding judge stated that it looked like egregious abuse.

In Apple’s case, its federal judge wrote that around half of the tens of thousands of documents designated as privileged were later downgraded. The business press has speculated that even though the excess privilege-mongering often gets reeled in during the court process, the obfuscation slows down the proceedings, delaying the day when the firms are finally legally forced to make changes. With entities like Apple making billions annually off their monopolistic abuses, like barring apps from accepting payment outside the official App Store, even foot-dragging on compliance for mere months can mean savings in the billions for companies of this size.

These especially brazen practices, put in place in clear expectation of lawsuits, suggest the fundamental weaknesses of the antitrust system. Giant amounts of money allow fighting hard through every trial and appeals hearing, pushing back timelines for changes. And of course, the very best the system can be hoped to do is break up a monopolist, creating an oligopoly of still-enormous and exploitative companies. But if anything might lead the judges overseeing these cases to actually try to punish these platforms, it could be the indignation of the liberal bench at Big Tech deliberately thumbing its nose at the legal process and brazenly withholding so much relevant material.

All these antitrust battles and their appeals will take years, as these companies continue to choose which ideas to surface and which to bury down the feed for millions of users, which politicians to pour money into and which media entities to buy and add to their empires. Legal headaches aren’t likely to limit their power, standing as they did directly behind the new US president at his inauguration. While the techlash continues, the great platforms still have the whip hand.