This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

The acclaimed garden writer’s latest book is part memoir, part garden guide and part call to action.

On a sunny day in late April, Barbara Damrosch, 83, stepped into boots and out the back door into the stone courtyard of her home in Brooksville, Maine. Thyme crept over the tidy rock pathways and lavender hedges climbed waist-high, soaking in the mild coastal climate. She pointed out other hardy perennials—thick green lances of sorrel and stalks of celery-like lovage—commenting that the garden wasn’t much to look at this time of year. Around the corner, thickets of daffodils bobbed in the sea breeze, as if shaking their butter-yellow heads in dissent, while the first asparagus stalks pierced through soil as rich as chocolate cake.

Damrosch has been gardening for close to eight decades and has established a career as one of America’s foremost writers about gardening. For her, gardening is inclusive of a wholistic approach to life: a pastime, a form of exercise, a source of healthy food, a point of community connection and an undeniably radical political act.

Barbara Damrosch crouches near a patch of sorrel, a hardy perennial with edible leaves, which she describes as having a “pleasantly sharp lemon flavor” in her new book, “A Life in the Garden.” (Kelsey Kobik, Barn Raiser)

“The urge to take control of our food supply is a sane one in times of insecurity, especially if we can do it in our own backyards,” she writes in her latest book, A Life in the Garden: Tales and Tips for Growing Food in Every Season (Timber Press, 2024). In it, Damrosch offers a tour of her life in the garden while serving up her signature wisdom and wit, alongside a call for others to join her in tending the earth and celebrating the harvest.

(Timber Press)

In 1977, then in her 30s, Damrosch traded her New York City apartment and job as a college teacher for a house in the Connecticut countryside and a role as a professional horticulturalist. Two years later, she launched her own landscape design firm. In 1982, she published her first book, Theme Gardens: How to Plan, Plant, and Grow Sixteen Glorious Gardens. Its first chapter, “A Garden Primer,” became a springboard for her next book, The Garden Primer, first published in 1988, which has gone on to sell more than half a million copies.

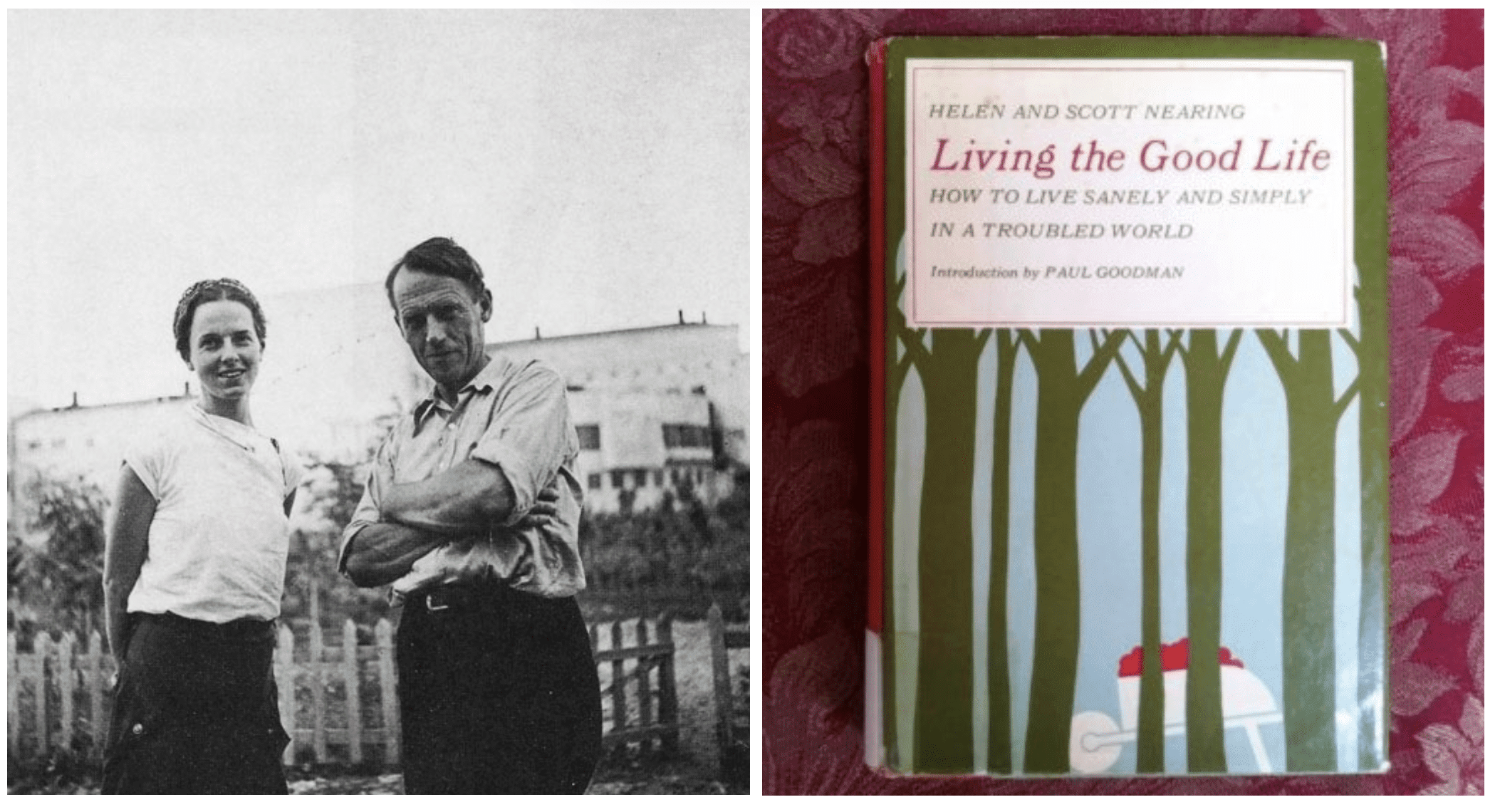

Damrosch married fellow author and farmer Eliot Coleman in 1991, and the two began collaborating in the field as Four Season Farm, as well as on the page—similar to another iconic gardener-author duo, Helen and Scott Nearing, whose Living the Good Life is credited with launching the back-to-the-land movement. Damrosch counts the Nearings as a major influence on her relationship to the land; in fact, Four Season Farm is sited on acreage previously owned by the Nearings, purchased by Coleman in 1968.

From 2003 to 2017, she wrote a weekly column for The Washington Post called “A Cook’s Garden,” and for many years she was a correspondent on the PBS series The Victory Garden, and co-hosted the series “Gardening Naturally” for The Learning Channel.

Barn Raiser spoke to Damrosch about her life as a gardener and a garden writer, her approach to gardening as a source of healthy food and a point of community connection, as well as the joy and independence that gardening still brings her. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Why do you grow food?

The book begins with my being exposed to my grandparents’ garden in Louisiana. I was a city girl, living in New York. And I loved it out there. I loved roaming the place—they raised their own supply of fruits and vegetables. It was partly my mother’s upbringing. She was a wonderful cook and wanted to have good ingredients. And so, we all got involved. I had two sisters and we all enjoyed gardening. It was the pastime. We liked hiking and a little bit of cross-country skiing, but that was really what we did as a family.

What are the reasons you garden today?

You could start with the political side. It’s a way of controlling your life. There’s a lot of ways we can’t control the world around us. One thing we can control, if we want to embark on it, is getting our own food supply. For a lot of people it could be an economic necessity or improvement. In my case, it’s the satisfaction of knowing how fresh it is, what’s gone into growing it, how it tastes, the fact that it’s right out there—I can go grab it.

A lot of people think they can’t garden. You can garden in a very small space. Your backyard has no sunshine, let’s say, but your front does. Well, grow it in front. It can be just as beautiful, if you keep it well.

It’s hard for some people to find time, but you don’t need a lot of time. Just grow some of your favorite crops. Some of the ones that taste so dramatically better when homegrown, like tomatoes or freshly harvested. You don’t have to have a two-acre orchard. It’s nice. But one tree might be it.

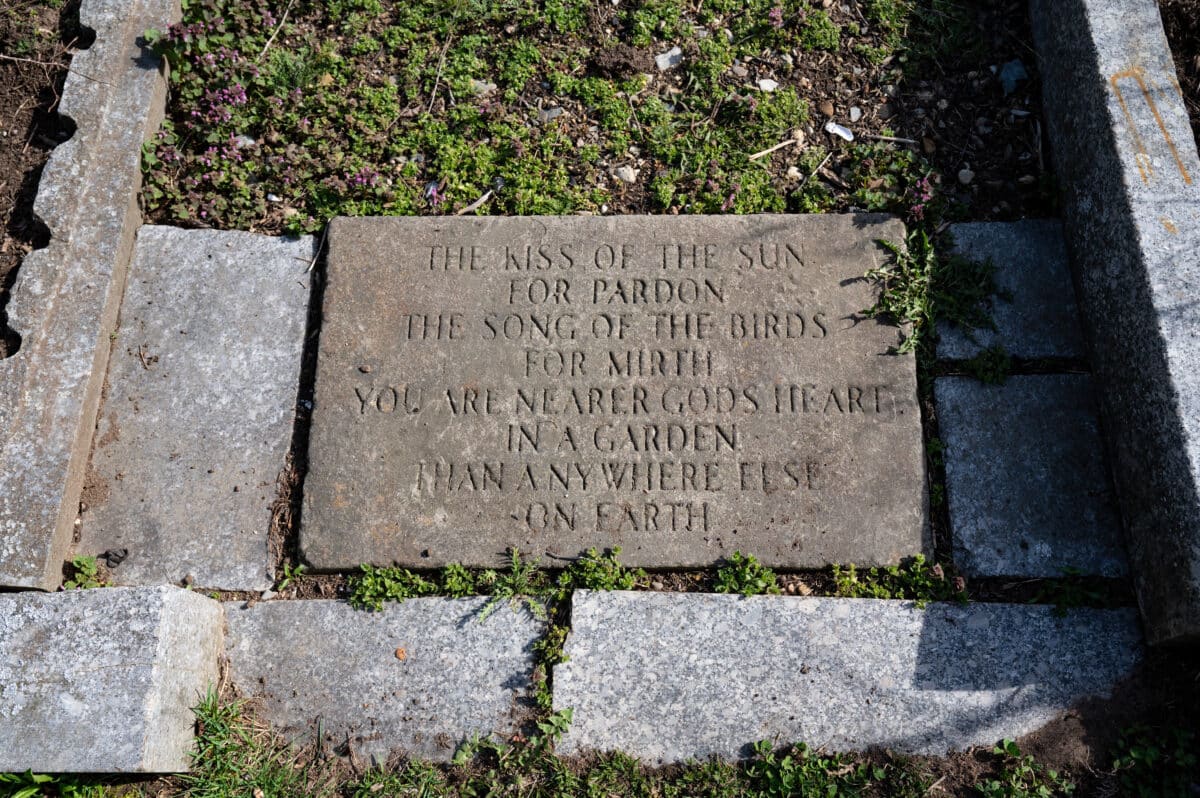

A garden stone engraved “The kiss of the sun / For pardon / The song of the birds / For mirth / You are nearer God’s heart / In a garden / Than anywhere else / On Earth,” from the poem “God’s Garden” by Dorothy Frances Gurney. Before moving to Maine and joining forces with Eliot Coleman as Four Season Farm, Damrosch owned and operated a landscape design firm in Connecticut. (Kelsey Kobik, Barn Raiser)

In that list of reasons for gardening, you mentioned the political first. You write: “I have sometimes read about creatures that are inherently savvy about imminent danger, like the wild animals that race inland and upland when they sense from far away that a tsunami is coming, or dogs that can tell if you’re about to have an epileptic fit. I like to think that we too have an innate scrap of good sense that tells us, when the outlook is dark, to head for the nearest piece of earth and make it bountiful.”

This is in the context of you citing World War II, the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic …

World War I too.

As times in history when people take to gardening en masse. But then you talk about how the trends also shift during more stable times. Right now, in this moment, what do you think it’ll take to create a more consistent culture of gardening?

In one answer, I would say education. I think Alice Waters got it right. [Restaurateur Waters launched The Edible Schoolyard Project in Berkeley, California, in 1995]. We need to teach children to garden when they’re young. You teach people to play the piano. You teach people to do math. You teach people to drive a car, or ride a bicycle, or say “I’m sorry” if they bump into you. It could just be part of anybody’s education. And we used to, long ago, absorb it by osmosis if it was being done around us. But if that’s not happening, I think a school can make a huge difference.

Not every school has the space to do it. But the ideal city would have a space that any school could use, even if it’s just a small plot.

What are some of the misconceptions that people have about getting started gardening?

Really all you need is one little row of tomatoes, just a few plants. Here’s some lettuce, let’s say, and here’s some kale. And, here’s some beets. You get the greens and the roots. You know, these double-crop plants.

And you could easily have fresh food year-round.

Eliot [Coleman] has pioneered ways to take advantage of the seasons where plants actually prefer cool weather as opposed to hot. All of the fruiting ones have to be in summer, to get to that fruitiness and make their seeds and all of that. Corn, tomatoes. But all of the greens don’t like it when it’s really hot, with few exceptions. So, you take advantage of what’s in season—you eat with the seasons—and you can do very, very simple structures.

We are always experimenting and trying out the best way to sell the idea to the average person and what you can make them out of.

Early season crops, including overwintered spinach and tulips, grow in a moveable glass house used for season extension. (Kelsey Kobik, Barn Raiser)

In addition to offering lots of practical gardening information, your new book has a lot of humor on the page, which I appreciate.

The new book has way more humor. I’ve always been a joker. Whenever anybody had to make a funny speech, when I was growing up at school and whatever, they would have me do it. I had no reverence.

When they asked me to start writing a weekly column for The Washington Post in 2003, which I did for almost 15 years, every week, I had to sit down—and I’ve always felt this way even before The Post—and think: How can I make what I’m sitting here all alone writing fun for me? How can I make myself laugh? Because that’s really the way it happens. You don’t just have a gift for humor, I think you have a need for humor. I can’t really explain why, but you really just want to see the looniness of life. So, having to do this thing every single week, I just tried to make it entertaining—for writer and reader.

With almost anything, you should have laughter. I had a grandfather, not the one in Louisiana, but the other one who was an Episcopal priest in Pennsylvania. He had a little bookcase beside his favorite chair. And I would sit in his favorite chair and pull out Fun in Church, More Fun in Church, Lapses in the Apses, Smiles in the Aisles. They were all humor books about religion, about church, and I just loved that. And that was kind of the way I was raised. Everybody on that side of the family would compete. Who was the funniest? Even as a child, I would try to join in with bad puns and all kinds of things.

Gardening and writing have been twin pillars in your life. Have you learned more about gardening as a writer?

In 1967, I was living in New York and I was working on a Ph.D. at Columbia in medieval comparative literature. I started writing in 1972 to earn money to survive in New York. I would write about political things, mostly feminist. I wrote for The Village Voice, places like that. But I did some funny pieces for Esquire. Whoever would pay me money, I would write for them. When I moved to Connecticut in 1976, I knew that growing food was part of it, because, from my mother’s side of the family, I had that legacy. I wanted to move to Connecticut and raise my son in a nonviolent neighborhood and I really wanted to grow food. It was something I had a hunger for. And so, when I got to Connecticut—it was a house that my great-aunt had lived in and then passed away, and my parents inherited it—I started. I edited the town paper [The Sherman Sentinel]. I was also trying to send stuff back to New York, but it was a little hard making what was on my mind interesting for New Yorkers. So I started writing about gardening.

You’ve had the opportunity sit with your ideas and explore them on the page. I’m wondering if you felt like you grew as a gardener?

Well, in the beginning, yes, because I was doing a lot of research. I was reading a lot of garden books. And the other thing that happened to me is I married this dude [Eliot Coleman] who knew a lot about gardening. He was a mentor for me. I knew quite a bit, but there were lots of branches, especially with food growing, that I didn’t know. He didn’t know anything about flowers. We’ve had a great time doing all this shit together.

In the book you write that two of your mentors were Helen and Scott Nearing.

I almost left New York just to be Helen and Scott. And I came to this house that my parents owned, but it was so not Helen and Scott. It had been built in 1690, but they’d added on all this modern stuff. There was room for a nice garden. I grew my food all right. I just dug right in. It was fun. I was a single mom. I had a son who kind of dug it, but it wasn’t all-engulfing for him like it was for me.

I was always trying to prove how strong I was as a little woman in a very mannish field.

Helen Knothe and Scott Nearing in 1931 and “Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World,” published in 1954. (Schumacher Center for a New Economics)

When I started writing about gardening, I had a landscape design firm. A lot of New Yorkers were coming up to Connecticut and wanting trophy gardens.

I would take on clients and completely transform their yards. I was planting trees with large root balls and things like that. It’s sort of neurotic and dumb, thinking about it, but I really was trying to prove that I wasn’t this powerless, hopeless little stick of a person.

I had been the smallest girl in my class. Even the class below me didn’t have a girl as little as me—and it was a girl’s school. It was the big volleyball stars and basketball players that got respect.

How did you get from Washington, Connecticut, to Brooksville, Maine?

I was protesting the Gulf War in Washington Depot at the village green one day. Every Wednesday, I think it was, we would have a protest and there’d be this huge banner saying, “We love our troops. Bring them home now.” This other woman and I held different poles, and, while we were doing this, she revealed that she had a house that she rented in Maine—in Brooksville.

It turned out that not only were they renting a house in Brooksville, but Helen and Scott Nearing did not live in Vermont the way I thought they did. They lived in Brooksville, and so did Eliot Coleman—whose 1989 book The New Organic Grower was in competition with mine and vice versa. He was told by his publisher the real threat to his book was not Rodale, it was that “little woman.”

So, it all kind of happened. My friend Davyne in Connecticut took me over to see Helen. We just walked in—she’s used to that. And there was Eliot in the greenhouse with her tying up her tomatoes. He showed me around her place, showed me around his place, took me out for pizza, and the rest is history. We just go along. And that was 34 years ago.

Speaking of some of these mentors, I want to ask about a different kind of mentor. You write about gardening in nature’s image and looking to nature as a guide for your gardening. That seems to be a big part of your life, to not only participate in gardening and cultivating food, but to do it in a way that is in alignment with the world.

Right.

What led you in that direction and what lessons have you learned by embodying that?

I think of it not as an opinion but as a fact. I’m not pigheaded about it. We are all completely subject to nature’s laws and you come up against them more intimately in the garden than you would, say, brokering stocks and bonds.

It’s not physical versus non-physical. It’s much more the holistic view of our place on this planet, what we’re doing to it, what we should be doing.

Damrosch assesses the first shoots of asparagus in the vegetable garden. In her latest book, she writes about how she and her husband Eliot Coleman celebrate the first harvest of each new crop—whether peas or pumpkins—by sharing it with one another. She said, “It’s a little mini celebration every day.” (Kelsey Kobik, Barn Raiser)

It was part of my rebellious ’60s, ’70s way of thinking. I wasn’t the only person thinking that way then, but it was indelible to me. My lefty counterparts in Manhattan didn’t get it at all. To them the movement had more to do with labor unions and pacifism, which of course is very Nearing-centric too. Paul Goodman, who wrote the introduction to Living the Good Life, was more of a pacifist anarchist, and that’s kind of where we all were.

A lot of people, especially my colleagues when I was teaching at Cooper Union, just didn’t understand why I would want to come up here and, as a partly political act, grow my own food. They found that completely frivolous and unimportant. I didn’t give a shit.

You also describe gardening as an art. I want to go back to that.

Gardening is not so much a kind of a belief system as an expression of your personality. Somebody who I absolutely worship is Ruth—what’s her name?

[Barbara goes in the adjacent office to ask Eliot, who is editing his forthcoming book, The Self-Fed Farm and Garden: A Return to the Roots of the Organic Method.]

Eliot: Ruth Stout.

Ruth Stout—her most famous book is what?

Eliot: How to Have a Green Thumb Without an Aching Back.

Yeah, that’s probably the most famous one.

She hardly weeded at all. If she did weed something, she just threw it on the ground as a mulch. She mulched and mulched and mulched. People would walk in, having heard all this praise, and they’d see this messy place. There are all different ways of doing it. She was feeding herself just fine—and her husband.

There are so many different trends like this that are interesting to talk about. Like the latest is no-till. Eliot and I are pro-till. You just have to sometimes do it. You do it shallowly, carefully.

We’re very committed to organic. The word has been completely destroyed by the USDA [U.S. Department of Agriculture] because they’re certifying organic things that are hydroponic. We happen to believe that soil is extremely important. Hydroponics uses no soil, and it is just not as quality for us from what we know of nature. We all used to get manure from farms. Nowadays we’re much more careful about that. USDA is certifying people who may get manure from farms that are not organic and God knows what’s in the poop.

Eliot: We no longer bring in manure, love.

I’m about to get to that.

Eliot: When you get to our age, remembering a name like Ruth Stout requires two minds.

Yeah. Both of us.

Eliot: We each have half of it.

Half the time, I don’t know even know who he is.

How you are adapting to …

Old age?

To growing food as you continue your life in the garden?

Well, I just came from the guy who treats bones.

He’s more like the conventional medicine side of orthopedics. He had me fill out a thing, saying what does old age prevent me from doing?

And I kept crossing out the word “prevent” because it was all based on anything that hurts. He said, “I understand that all these things give you pain, but you did them anyway.” And he said, “That’s exactly what you should do.” Because it does keep me moving. You have to keep moving.

That’s why I really urge people to at least try to do some gardening. I mean I have some helpers when we can get them. Sometimes it’s not always easy to find. Eliot is 86 and I’ll be 83 in July, and we go out there and just do the things we usually did, except maybe not quite as drastically and as regularly. We’ve cut it down to just a home vegetable garden.

There are different parts of your body that are more vulnerable than others. But I think that movement and, to some degree, weight-bearing exercise is good for you. I have arthritis that I got from my mother and there’s nothing I can do about it, I simply have it, but I don’t let it keep me from doing stuff. I can’t do what I used to do at the depth that I did it when I was planting trees with big root balls. But sometimes it’s a question of mind over matter.

Are there adaptations that you’ve made in the garden?

One of my philosophies is the way in which nature does the work. For instance, the fact that everything rots down and puts organic matter into a usable form in the ground, with the help of all these organisms that are there, whether it’s in your compost pile or whatever. That’s a case where you’re not even doing the work. And like what Ruth Stout cast on the ground, earthworms would come and drag them down into their burrows and everything would decay over the wintertime and it would be soft, nice, friable, loose soil because of her crap that she threw around. That’s a concept that a lot of people don’t know at the beginning.

They think they have to buy everything. And that’s why Eliot’s upcoming book is so important because it’s this idea of a self-fed garden, a self-fed farm. You don’t have to buy stuff. Everybody wants to sell you something in this country. In the old days, it wasn’t quite that way. You didn’t have endless bags of stuff that you’re buying all the time. You’re letting nature just do this for you. Leaves fall from the trees and turn into soil. That’s the way it is.

You need the right tools. You have to have a good, sturdy contractor’s wheelbarrow. The right kind of spade, the right kind of shovel. I even have something called a mattock. It’s a great tool. It’s heavy to lift, but you get that gravity weight of it coming down. And even more than digging, sometimes it’s the best way to hack up heavy ground.

What other things would you encourage gardeners, either new or seasoned gardeners, to do?

A lot of my feeling behind this has to do with how we eat as much as anything. I find that, living out here in the country more than back when I was in the city, people here become kind of faddish about their diets. I don’t want to be accused of being insensitive about this because I know some people can’t take gluten or can’t take dairy or this or that.

But a lot of people glom onto certain fads and, for example, think that all gluten is bad. Currently, everything has to have protein. They’re even selling you protein powders. I don’t think they taste very good. It’s always something like that.

Things are much simpler. Yes, nature is infinitely complicated. I understand that. I could look through a microscope and figure that out. But the way you deal with nature is surprisingly simple. That’s why going back and reading the history of how things were grown is really interesting. It hasn’t changed that much. The systems that we use are very primitive. We really are peasants here if you understand the basics of how to feed ourselves. It’s sort of sticking to those basics and not being led by quickie solutions in bottles and jars and bags.

In terms of this political moment, how are you staying grounded?

I’m discouraged. I’ve been through a lot of bad leaders, a lot of bad decisions that made changes for the worse. There are so many things I’ve seen, and sometimes things improve and sometimes they don’t. But you do have to fight for what you believe in. You can’t be afraid to do that. Even if it upsets the mood of the cocktail party or whatever.

I read the papers for quite a long time every morning. So does Eliot. I want to be informed. I think honestly what I’m looking for is that little tidbit of hope, like the little graph that shows how low Trump’s popularity rating is at the moment. Even if it’s just a little bit, you want to look for some signs that I’m not the only person that feels the way I feel.

The kitchen plays an important role in Damrosch’s life as a gardener. Her new book details how she eats with the seasons, sharing tips for both the garden and the table. (Kelsey Kobik, Barn Raiser)

The judiciary is in a complete muddle over what a district judge can do now, what Trump can do now and, and maybe can we actually let Congress do something about a law? It’s a mess. We’ve almost got to rewrite the Constitution or maybe read it louder so that people can hear what’s in it.

An awful lot of people are dissatisfied right now. I’m not the only one. Look at all the demonstrations. Bernie [Sanders] and AOC [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez] getting thousands and thousands of people, whole stadiums of people. What a combination. I just love it. So that makes me happy. I’m really worried about the planet. The quality of life is deeply disturbing—the threats to life.

Do you think that gardening and farming and people who are returning to caring about the food system …

Oh yeah, we’re doing our bit. We’re not solving every problem. I think it is definitely a healthy, healthy trend. Absolutely. No question about it. Learning how to grow things, but doing it in a way that doesn’t disrupt. You don’t go around spraying poisons all over your garden. It might get rid of this bug, but maybe that bug was eating that bug. We’re looking for one single answer in a can: a spray can. It’s insane. You need to open your eyes and sometimes you need to read. The things out there that are happening are very, very tiny. A lot of them you can’t see at all. Or you may see a bird doing something, but you don’t know why it’s doing that. It is a combination of being out there in it, observing it, but also reading what people have studied and found out.

It almost sounds like there is an element of trust or faith: You’ve read things but you also trust that there’s a possibility that that bug is doing more.

There’s too much fear of nature right now. I talk about a fear of food. The people who are suddenly terrified of gluten, let’s say, that everybody should be afraid of gluten. But sometimes it’s fear of nature. It seems so overwhelming, so out of our control, and that’s okay. No one organism rules the planet. We may think we do, or we need to, or we’d like to, or we’re trying to. We’re overlooking what is going along just fine. I often just say gardening is standing back and taking a look and seeing what nature’s already doing and not stand in its way. That’s it in a nutshell. If I had to put it all into one sentence, it would be that one.

Teaser image credit: Author supplied.