On “The Message,” a trip to Jerusalem and the West Bank, and the moral duty to break the silence.

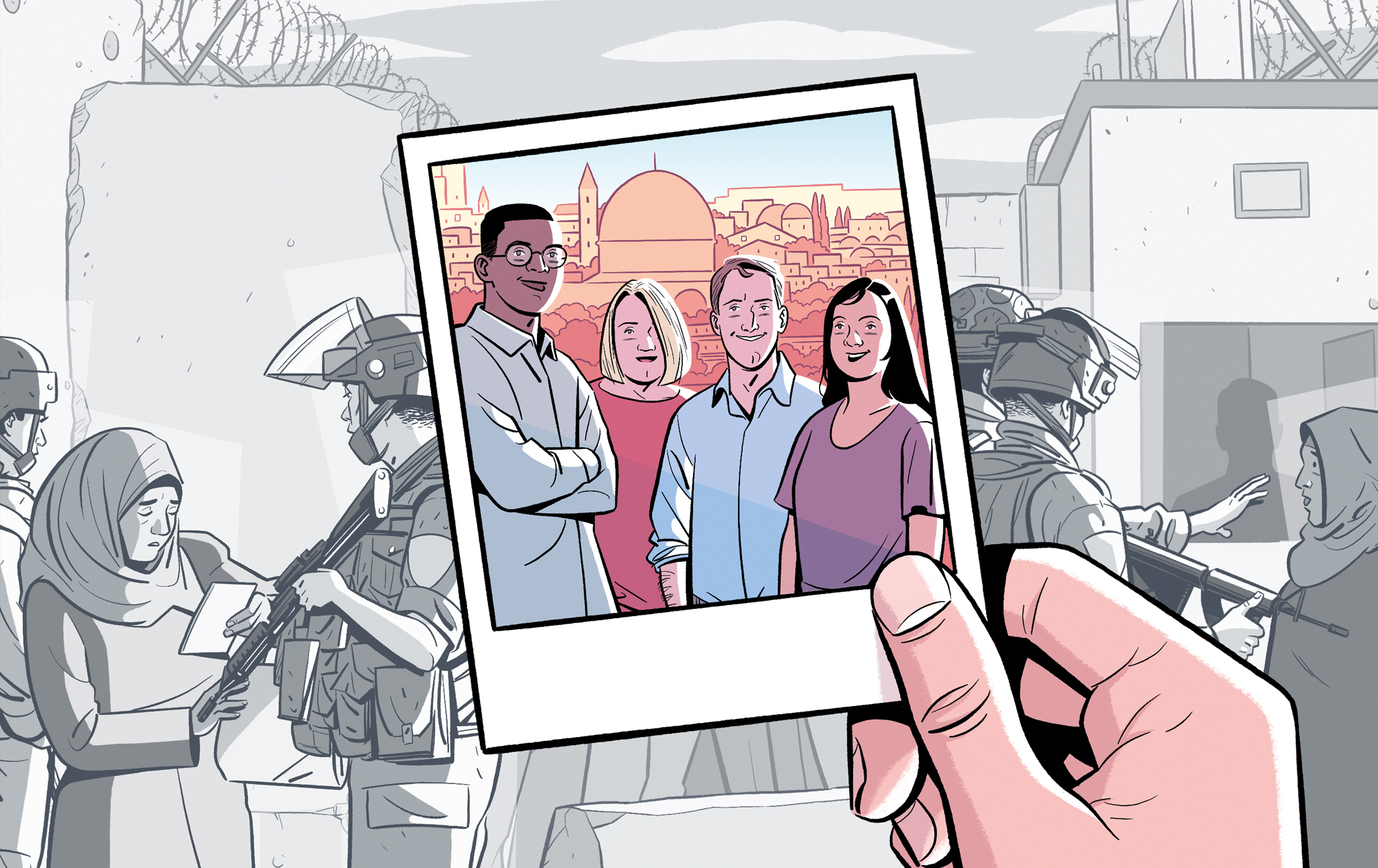

“We do injustice to Gaza when we turn it into a myth, because we will hate it when we discover that it is no more than a small poor city that resists.” – Mahmoud Darwish, “Silence for Gaza” “Your silence will not protect you.” —Audre Lorde Eleven years ago, I stood smiling before the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, posing with other Christian tourists as cameras clicked around us, eager to capture proof of our spiritual devotion. We were on a pilgrimage designed to draw us closer to the sacred. Yet just beyond the frame of our photos, checkpoints loomed, armed soldiers patrolled the streets, and Palestinian life endured under occupation. We cropped those inconvenient truths out, not only from our photos but from our consciousness, desperate to preserve the purity of our religious experience. At the time, we believed we were innocent pilgrims. But I now understand that our sense of innocence masked a deeper truth. We were complicit. That memory, along with my struggle to face my own complicity, has clarified how easily faith can become a veil that obscures our proximity to violence. It has made me think about how often, throughout history, ordinary people have borne witness to brutality not with resistance, but with silence—or worse, with a smile. I used to wonder how someone could stand beneath a lynched Black man—dangling legs grazing the tops of grease-slicked hair, wide-eyed children staring in bewilderment nearby—and pose for the camera. What kind of world cultivates such moral decay that families could discover joy in the public spectacle of Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze? Then I read “The Gigantic Dream,” the final chapter of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s latest book, The Message. In it, Coates reflects on his visit to the West Bank and explores the parallels between American racial apartheid and the Israeli occupation of Palestine. His vivid observations—of segregated roads, militarized borders, and the quiet complicity of onlookers—made me feel something I couldn’t ignore. As shame washed over me like cold February rain—slow, steady, and sobering—I began to recognize in those silent onlookers a part of myself. The person I had long condemned for their inaction, their silence in the face of white supremacy and racial terror, their ease in the shadow of death, lived in me too. Reading Coates’s book helped me make sense of two awakenings I’ve experienced in recent years. The first came in 2022, when I testified against book bans in Columbia, South Carolina, and confronted what I’ve come to see as the growing politics of silence in American education: not merely the silencing of authors and ideas, but also the quiet complicity of those who fail to speak out against such censorship. The second surfaced more recently, as I revisited memories of my 2014 trip to Israel and the willful blindness I carried with me. Coates’s writing offered a lens that helped me see the connection between these personal discomforts and the larger systems—systems of segregation, displacement, and control—that shape modern global politics. In The Message, he reveals silence not as absence but as a force, binding people to violence from the Jim Crow South to occupied Palestine. When I stood on Jerusalem’s soil and crossed the Sea of Galilee—accompanied by my girlfriend at the time (now my wife), and mindful of my mother’s pride in my pilgrimage to Christianity’s birthplace—I gave little thought to the sociopolitical realities that stirred my brief discomfort. It was a sacred moment in our shared faith journey, one that deepened our spiritual bond even as it left certain questions unspoken. Like Coates, I bristled as we were guided through military-managed checkpoints, perhaps because I have always been uncomfortable around the police as a native of the South Bronx and a child of the hip-hop era. But even as I sensed that something felt off—the way people moved with hesitancy and unease—I avoided looking around to witness the indignities unfolding before me. Instead, I closed my eyes, clasped my hands, and whispered a prayer of thanks to my God for the privilege of touring temples and shrines that had once been merely names in my Bible. In the name of sacred awe, I surrendered my vigilance, allowing faith to become a filter—one that let me sanctify the moment while editing out the suffering that might have complicated my praise. I prayed, journaled, smiled for the camera, and wept tears of joy while standing inside the tomb of Jesus, only a stone’s throw away from the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the place where the Prophet Muhammad is believed to have ascended to heaven during the Night Journey. I allowed myself to sink into an individualistic well of thanksgiving while ignoring the layered traumas haunting the land. And now, I am beginning to understand how one can claim allegiance to Christianity while pledging fidelity to systems of oppression like slavery, all while standing in a field of strange fruit hanging from oak trees. You simply have to close your eyes. Long before the shame of realizing I had been complicit in the brutality against Palestinians in Gaza, I found myself standing before the South Carolina legislature in the spring of 2022, defending books that do what Coates believes great writing should always do. They should haunt, he insists: “Have them think about your words before bed... [have them] grab random people on the street, shake them, and say, ‘Have you read this yet?’” It was my first year as a law professor in South Carolina, and I was testifying against bills designed to ban books and other instructional materials examining race, racism, and American identity through a critical lens. The irony struck me only later. Here I was, defending books that exposed uncomfortable truths about American racism, yet I had failed to recognize a similar system of oppression during my pilgrimage to Israel eight years earlier. In Chapter Three of The Message, “Bearing the Flaming Cross,” Coates reflects on what it means to be American in an era when books by Black authors are being banned from school libraries, simply for revealing uncomfortable truths. After returning from a trip to Africa, he finds himself in Columbia, South Carolina, where elementary school teachers are being targeted for allegedly violating book banning laws, and in one instance, for teaching his National Book Award winning memoir, Between the World and Me. Both Coates and Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said expose how dominant institutions use education not to liberate but to domesticate, replacing curiosity with conformity. As Coates asserts, “The danger we present[…] is not that we will simply convince their children of a different dogma, but that we will convince them that they have the power to form their own.” The protesting parents who want to keep Coates’s books out of schools may not be so much concerned with their children’s discomfort as with the possibility of their children challenging long-held beliefs about what it means to be American—beliefs that, in turn, would force such parents to confront their own unexamined complicity with white supremacy. What I saw that day while testifying before the South Carolina legislature was fear—fear of writing’s power to expose hypocrisy and awaken moral imagination. As Coates puts it, “Politics is the art of the possible, but art creates the possible of politics.” Writers are called not only to tell the truth, but also to confront their own place in the world. They are artists, and great art—from films to memoirs—can reshape politics. It was art, after all, that helped distort the promise of radical Reconstruction into the stain of Jim Crow, through works like Birth of a Nation and Confederate monuments to men like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Coates’s art threatened to shift that legacy once again, stirring the political imagination of South Carolina’s youngest citizens. As Said reminds us, “the power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging” is everything. Coates could have ended The Message there, but we live in a globalized world, and our understanding of what it means to be American must confront our global footprint. Chapter Four, “The Gigantic Dream,” shifts focus, guiding the reader through Coates’s reflections on his visit to Palestine in May 2023, just months before the October 7 attacks by Hamas. This was the moment in my reading journey when I encountered the shame that would eventually transform me. Like the child standing below the legs of the hanging slave, perhaps naiveté had initially clouded my judgment. I had never been taught the full history of Palestine or Israel. Despite learning about the Crusades in Catholic school, I had never heard that story—or more recent religious conflicts—from the perspective of the Muslim, the Palestinian, the so-called “other.” As I turned the pages of The Message in late 2024, my memories of Jerusalem began to shift under the weight of Coates’s analysis. Each paragraph connecting the Palestinian experience to the African American freedom struggle created a bridge between his observations and my incomplete pilgrimage. Jerusalem holds deep significance for Christians, Muslims, and Jews alike. As Coates explains, “Muslims believe that Al-Aqsa is where the prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven,” and “all three Abrahamic religions—Christianity, Judaism, and Islam—believe Temple Mount to be the site of a temple built by the biblical King Solomon.” Nearby stands the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, built where Jesus was crucified and buried. Yet Jerusalem remains divided. The Old City contains quarters historically associated with different religious communities, while modern Jerusalem is split between east (largely Palestinian) and west (largely Israeli). What I didn’t fully grasp during my 2014 visit was how Jerusalem’s division mirrors and intensifies Jim Crow-era segregation. The system of checkpoints, where armed soldiers scrutinize and regulate Palestinian movement—particularly for those Palestinians with darker skin—reveals the entanglement of racial profiling, religious identity, and state surveillance. Palestinians within Israel hold limited rights, while those in occupied territories face even harsher restrictions. Arab citizens remain third-class within Israel’s borders, facing systemic discrimination in housing, education, and public funding, while Jews of color, particularly Mizrahi and Ethiopian Jews, experience entrenched marginalization. It is a society governed by separate legal structures for different populations, amounting to what many now call a modern apartheid state. This system of racial hierarchy is bitterly ironic given the rich legacy of Jewish solidarity in the fight for racial justice. During the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, for example, Jewish leaders like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel stood alongside African American activists such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., recognizing a shared struggle against dehumanization and state violence. This history is not a footnote. It is a vital reminder that the pursuit of justice has always required crossing boundaries of faith, race, and nation. Reading Coates’s description of the brutal realities he encountered in Israel and Palestine, I remembered walking through some of those same checkpoints myself, my American passport granting me passage while others waited behind. I had noticed the guns, the tension, the separation, but I chose not to see them as part of a larger system of oppression. Instead, I turned my camera toward ancient stones and biblical sites, carefully cropping out the modern apparatus of occupation. Before wrestling with the implications of state-sanctioned separation, Coates allows his personal confrontation with this reality to challenge his earlier beliefs. In his Atlantic essay, “The Case for Reparations,” he had embraced the narrative of Israel as a democracy, albeit one riddled with complexities. Now, forced to reckon with his “ignorance of the world beyond America’s borders,” Coates concludes, “you can see the world and still never see the people in it.” I, too, needed to confront my earlier beliefs. It was here that I began to feel the shame I hadn’t felt when I returned from Israel in 2014. Unlike Coates, I had boasted a passport full of stamps when I visited Jerusalem. Yet, when I returned home—my bag weighed down by a journal full of prayer reflections and a camera full of tourist photos—I thought little of the systems of oppression I had witnessed and tacitly endorsed. Instead, as I exited the plane, I scrolled through photos of myself at the Dome of the Rock, the Western Wall, and the Sea of Galilee—racial apartheid dangling just beyond the frame—and smiled. Now, I am beginning to see the connections between the systems of silence I have encountered—whether in legislative chambers where politicians move to ban books about Black history, or on religious pilgrimages where tourists carefully crop out the uncomfortable images of occupation. I realize now that I had been so conditioned by the normalization of racism in daily life, so accustomed to the ways law legitimates social hierarchies, that I became a tourist in a land marked by racial segregation—and it barely disturbed me. Reading Coates, I was gripped by the hypocrisy of my Christian pilgrimage. As a Black American who has experienced racism firsthand, my willingness to overlook the state-sanctioned separation in Israel revealed a deeper blindness. It was a silence—the same silence that sustains police brutality, criminalizes poverty, and enables environmental racism—that prevented me from seeing how Palestinians’ experiences echo the Black American freedom struggle.The same impulse to silence dissent that drove book ban legislation in South Carolina also fuels censorship abroad—like the February raid in East Jerusalem, where Israeli forces stormed a Palestinian bookshop and confiscated its novels and memoirs and spiritual texts. Beyond the visible markers of separation, Coates draws attention to the ever-present threat of displacement looming over Palestinian life, a threat often justified as serving the “common good.” This logic mirrors the mid-20th-century urban renewal policies in the United States, which were often framed as revitalization efforts but led to the demolition of Black neighborhoods to make way for highways, commercial development, and other state-sponsored projects. Hundreds of thousands were displaced in the name of progress. As with these American policies, the displacement of Palestinians is often accompanied by a rhetorical machinery that cloaks violence in the language of improvement. Invoking Edward Said, Coates reminds us that there is always a “chorus of willing intellectuals” eager to sanitize empire’s violence, as if the destruction and death inflicted by the latest so-called civilizing mission could be explained away. Just as mid-20th century urban renewal displaced Black Americans in the name of progress (or as earlier efforts like the American Colonization Society during the 19th century tried to exile them to Liberia), so too do imperial projects today frame the control of a “backward” or “uncivilized” people as progress. Whether in the American South or in Israel, these efforts cloak domination in the language of destiny, even as dissenting voices within Israeli society and beyond push back against such myths. Reading the final chapter of The Message, I was struck by how my education had given me a narrow understanding of Israel as a redemptive response to the Holocaust, rendering Palestinians nearly invisible. Even Palestinian Christians, whose churches are vandalized, whose communities are surveilled, and whose worship is restricted, rarely pierce Western religious narratives. This selective history mirrors the way American education sanitizes the horrors of slavery and Indigenous genocide. As I toured the Holy Land contemplating Christ’s compassion for the marginalized, I failed to see the marginalized standing before me. I failed to see the oppressor in me. As Coates argues, “A system of supremacy justifies itself through illusion, so that those moments when the illusion can no longer hold always come as a great shock[...] and there is great pain in understanding that, without your consent, you are complicit in a great crime, in learning that the whole game was rigged in your favor[...] the pain is in the discovery of your own illegitimacy—that whiteness is power and nothing else.” Reading The Message shattered the careful framing that had once allowed me to experience my pilgrimage without moral conflict, exposing a reality far more complex than the sanitized narratives I had embraced. This reckoning surfaced deeper questions about identity and exclusion—especially how history reveals the fragile boundary of whiteness and Jews’ uncertain place within it. The same racism that fueled the mass murder of Jews during World War II left their postwar racial status in flux, a tension that Coates argues was resolved in part by recognizing Israeli independence in 1948 while restricting Jewish immigration to the United States, advancing the project of Jewish assimilation into whiteness through distance. It was a matter of keeping “them over there,” Coates asserts, and more to the point, “over there” engaged in a war against so-called savages. Drawing on W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of the “wages of whiteness,” Coates claims that whiteness operates not as a fixed category, but as a kind of political currency—offering psychological and material rewards to certain groups in exchange for their complicity in systems of domination. The systematic suppression of race-conscious education in the United States—from book bans to curriculum restrictions—has created a template for silencing critical perspectives on state formation and colonial histories, including those concerning Israel and Palestine. Just as laws targeting critical race theory claim to protect students from “divisiveness,” efforts to conflate anti-Zionism with antisemitism purport to shield Jewish students from hate, while in practice insulating the Israeli state from legitimate critique and punishing dissent. This suppression narrows Americans’ understanding of their own history of racial oppression and constricts the frameworks available to critically examine Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. Simultaneously, the U.S. government’s response to Palestinian solidarity protests on college campuses reveals the hollowness of its commitment to free speech and assembly when these rights challenge imperial interests. Palestinian and allied student protesters have faced surveillance, suspension, doxxing, and even deportation for peaceful demonstrations, signaling that certain expressions of political conscience carry severe consequences. This crackdown mirrors historical efforts to silence Black radical voices during earlier freedom struggles, demonstrating how systems of oppression recognize and fear solidarity among marginalized groups. Christian theology teaches that salvation requires acknowledging sin, not claiming triumph. The prophetic tradition, spanning from Amos and Isaiah to modern liberation theologians, condemns those who glorify sacred spaces while ignoring injustice. As theologian James Cone wrote, “Liberation is not an afterthought, but the very essence of divine activity.” Jesus himself condemned authorities for neglecting “the weightier matters of the law: justice, mercy, and faithfulness” (Matthew 23:23). Yet in my own pilgrimage, I failed to embody what theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez calls “a preferential option for the poor”: a recognition that God’s presence is found not only in holy sites but in solidarity with the oppressed. A true Christian response to the current crisis in Israel and Palestine must reckon with both how Jesus confronted empire and how empire has co-opted the mission of Jesus for its own ends. What remains is the immense violence, brutality, and death that has claimed the lives of thousands of Palestinian mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, and children in Gaza. These military campaigns, which many legal scholars and human rights organizations rightfully classify not only as war crimes but as genocide, continue to unfold under the justification of necessary security measures against terrorism. In truth, it is an indisputable humanitarian catastrophe—one that follows the familiar and brutal pattern of plunder, where a self-appointed master race systematically decimates its so-called savage people, all in the name of control and domination. As of July 2025, Israel continues to violate ceasefire agreements, launching new offensives after only brief humanitarian pauses. Civilian infrastructure is systematically destroyed, and medical facilities are deliberately targeted, despite global condemnation. This ongoing assault amounts to collective punishment, using mass suffering as a weapon of war. After 20 months, Gaza is nearly uninhabitable. What began as a military operation has evolved into the methodical dismantling of civil society. The intent behind these actions, increasingly recognized by legal experts as genocidal, is made clear by the staggering death toll—over 50,000 Palestinians killed, most of them women and children, hundreds of thousands injured, and 2.3 million facing catastrophic hunger and disease. Bombing hospitals, displacing families, denying basic necessities, killing innocent children: these are not mere policy decisions. They are assaults on human dignity, made possible by a willful ignorance rooted in histories that have been carefully sanitized by those in power. I now realize that the connections from the Deep South to the deep wounds of Palestine reveal something unsettling. My role as a Christian pilgrim was not that of a passive observer, but an active participant in perpetuating injustice through silence and smiles. My pilgrimage photos—carefully composed to capture spiritual moments against biblical backdrops—serve as evidence of my complicity. This realization requires more than acknowledgment. It demands a shift in how I engage with the world, a call to bear witness in ways that challenge systems of oppression. Bearing witness means acknowledging both my past complicity and today’s ongoing horrors: the destruction of civilian infrastructure, targeted killings of journalists, obstruction of humanitarian aid, and indiscriminate slaughter of innocent families, their lives shattered without mercy. I am reexamining how a faith centered on a Middle Eastern refugee—Jesus of Nazareth, executed by the occupying Roman empire—could align itself with modern powers of occupation. The discomfort I feel viewing my Jerusalem photos isn’t something to avoid, but to embrace. It’s a necessary step toward a more honest relationship with an unjust world. “If Palestinians are to be truly seen,” Coates writes, “it will be through stories woven by their own hands—not by their plunderers, not even by their comrades.” This ethic carries profound weight. It demands humility, acknowledging that our understanding is inherently limited by our distance from the oppressed. It requires courage, the willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, even at great personal cost. And it calls for relentless persistence, a commitment to continue telling these stories, even when the world chooses to look away. For me, bearing witness means engaging differently with Israel and Palestine, just as it means defending literature that confronts America’s painful, racist past. It means actively seeking out Palestinian voices, listening to anti-occupation and dissident Israeli perspectives, supporting organizations that foster dialogue and justice, and critically examining U.S. policy toward Israel. Most crucial to my own spiritual journey, it means challenging the sanitized narratives within Christian communities and creating space for uncomfortable yet necessary conversations about occupation, apartheid, genocide, human rights, and the rule of law. InSilence for Gaza, the poet Mahmoud Darwish warns against turning Gaza into an abstraction, a myth we invoke to feel righteous rather than responsible. “We do injustice to Gaza when we turn it into a myth,” he writes, “because we will hate it when we discover that it is no more than a small poor city that resists.” Perhaps, more than anything else, bearing witness means refusing the comforting distance of myth and metaphor. Listening to blood and rubble, not symbols and dreams. Ultimately, what I’ve learned from Coates is that true pilgrimage isn’t about visiting holy sites with closed eyes and clasped hands, but about opening our eyes to the pain and injustice around us. It’s about recognizing that the sacred cannot be separated from the political, that spiritual growth requires moral courage, and that bearing witness to suffering is itself a form of prayer—one that compels us to oppose hate and work to end it. In so doing, we might truly honor the radical Jewish prophet whose tomb I visited in Jerusalem with tears of selective joy. This journey is neither linear nor easy. It’s tempting to retreat into comfortable illusions, focusing on personal spirituality while ignoring the call for collective justice. But having seen what I have seen—through Coates’s eyes and, belatedly, through my own—I cannot unsee it. The challenge now is to live differently, to allow this awakening to reshape how I move through the world. Bearing witness offers no guarantee of redemption or resolution. But it offers the possibility of living more truthfully in a wounded world. And perhaps, fragile as it may be, that is where our hope begins.

-jpg.jpeg?width=741&height=1115&name=2014-06-03%2014-06-42%20(1)-jpg.jpeg)

The Author at the Dome of the rock, 2014. (Photo: Etienne C. Toussaint)

When Faith Obscures Occupation

Art Creates the Possible of Politics

You Can See the World and Still Never See the People In It

How nice, I thought to myself.

How nice.-jpg.jpeg?width=650&height=432&name=2014-06-05%2017-45-03%20(2)-jpg.jpeg)

The Author at the Monastery of the Temptation, West Bank, 2014. (Photo: Etienne C. Toussaint)

The Pain Is In the Discovery of Your Own Illegitimacy

Opening Our Eyes to Pain and Injustice