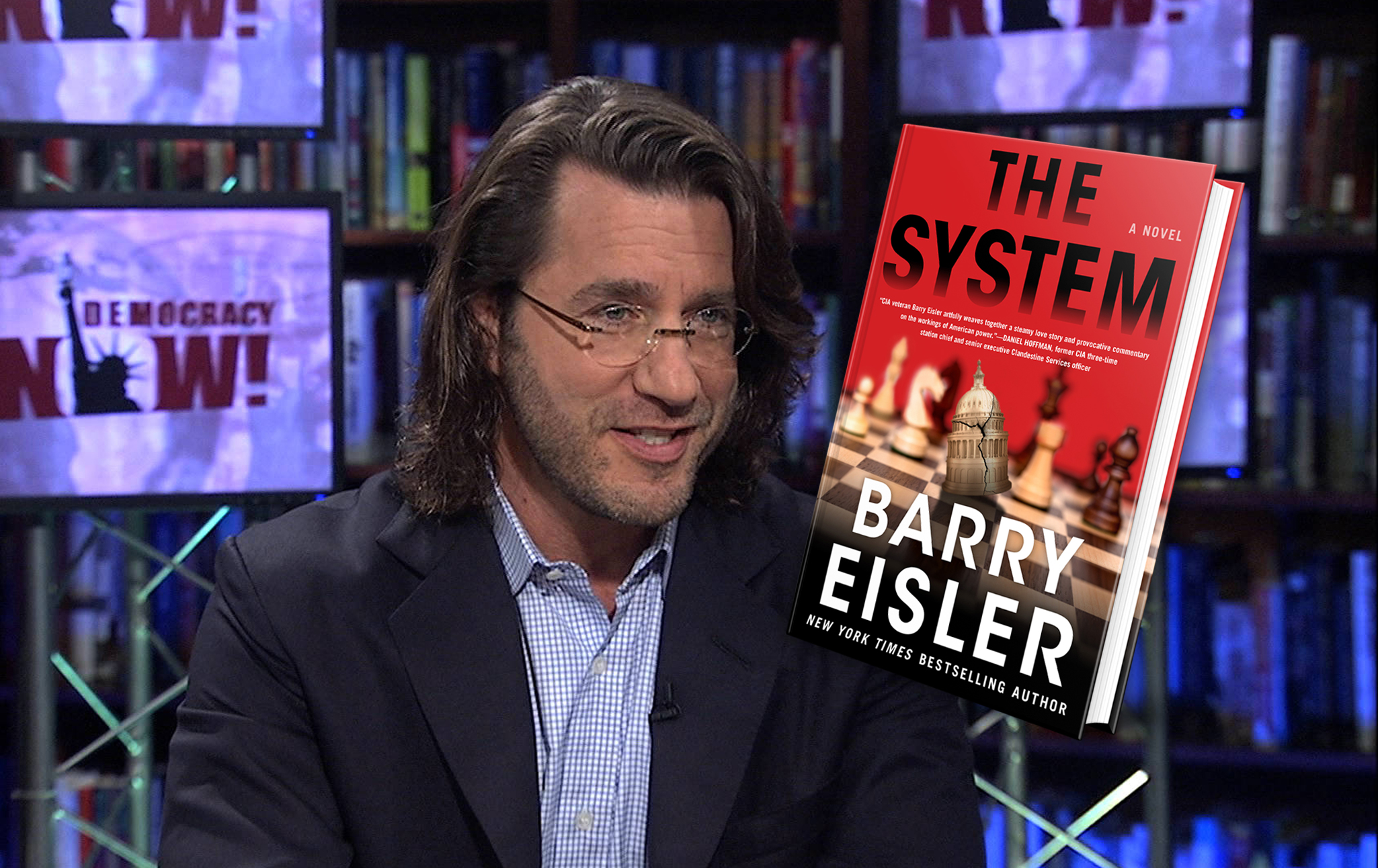

In bestselling novelist Barry Eisler’s new book “The System,” an idealistic young Representative discovers how power and propaganda really work.

Barry Eisler is a former CIA agent and bestselling novelist, known for political thrillers like The Killer Collective and The Chaos Kind. Today, he joins Nathan J. Robinson to discuss his newest book, The System. Eisler discusses how power actually works in Washington, how politicians get absorbed into the duopoly, why partisan conflict is mostly theater, and how language, fiction, and euphemism shape our understanding of violence, war, and the state. Your new novel has blurbs from some some great people, including friends of the magazine like Arnaud Bertrand and Ryan Grim, who are kind of unusual people to blurb a political thriller. But the thing about this novel is, and what’s so cool about it, is that this isn’t just a story or a piece of entertainment. This is a piece of almost sociology. This is like if Noam Chomsky was in your line of work. If you’re trying to make my day, it’s working. Well, it’s so cool because you’re not just telling a gripping story. There’s sex and violence in the story—there’s plenty to entertain people. The novel is called The System, and you’re really trying to show people, in kind of a realistic way, how power works, or at least that’s how I interpret what you’re doing here. But since you’re here, could you tell me what your interpretation of what you’re doing here is? That is exactly what I’m trying to do. That is the foundation of the book: how power is really exercised in America. And as you said, of course, if it’s not entertaining, then I haven’t done my job, and I shouldn’t write a novel. I’ll write a blog post or something like that. So I hope that people will find the story of Valeria Velez, who at the beginning of the book has just been elected to represent California’s 27th district as the youngest woman in Congress, super compelling and just can’t stop turning the pages. Again, if I haven’t done that, then I haven’t done my job as a novelist. But what I really hope is that when people finish the book they’ll come away with, if not a different understanding of how power is actually exercised in America—by whom and for whom—then at least I hope they’ll be more open to a different way of seeing how power is really exercised in America. I think we ordinary people are heavily propagandized. I don’t even think that’s disputable, but we’re heavily propagandized in a lot of different ways. And one of the consequential ways we’re propagandized is into thinking that there are actually two political parties in America that represent quite different choices, and we can choose whichever one we want; power is mostly vested in the government, and then we have these two very different parties we can choose between, depending on our own preferences. And I think that’s absolutely a fiction. If you were to do a Venn diagram of all the most consequential issues that might be addressed in a society or by the government, and one would represent the Democratic wing and the other would represent the Republican wing, you’ll see almost total overlap. There will be some important differences—very few, for example, on matters like abortion. Yes, that’s a quite important and consequential difference between the two wings of the party, no doubt. But there are so many other issues that are extremely consequential. I’ve gone on about them, like how income is distributed in this society. How much money do we need to pump into “defense”—propagandistically called “defense”—and on and on? So really, these two things that call themselves parties I think of more as two wings of the same party. Don’t take my word for it. For anybody who’s resisting this notion, it was Obama himself who said that politics in America is played between the 40-yard lines. So I don’t make any of these points explicitly in the novel. I don’t want to hit anyone over the head. I want you to be entertained. But as you see, the way power is really exercised and by and for whom, hopefully, at the end of the book, you’ll be open to a slightly different point of view. Maybe you’ll have a good conversation with someone else who’s read The System and try to decide, what does it all mean? Well, the guest on the program just before you was Ralph Nader, who made a very similar analysis of the two-party system. He has always emphasized the degree of overlap between the two, and so this won’t be too unfamiliar to our listeners. But it’s interesting to think why this isn’t obvious, and one of the reasons it’s not obvious is because the conflict between the parties is meaningful. So right now there’s this showdown on immigration. There’s Newsom vs. Trump, and so if people open their the pages of their newspaper, they’re going to see a standoff between the Republican president, who’s trying to enact a mass deportation program, and a Democratic governor. But what you’re saying there is, what you’re not seeing is the degree to which the two circles of the Venn diagram overlap on so many other things that go undiscussed—the things that you’re not seeing, that you’re not talking about. The reason that these aren’t in the newspaper is because the circles of the Venn diagram overlap, so there’s nothing to discuss. There’s no conflict. Absolutely. Why would it get reported? It’s not nearly as interesting. I think it was Banksy, who at least supposedly said, if you want to get attention, pick a fight. Because if there’s no fight, people tend not to pay attention. I’ll give you an interesting example of this. Some years ago, I wrote an article for your alma mater, the Guardian. And there’s an interesting story there having to do with Israel and U.S. government support for the government of Israel, which we’ll probably also wind up talking about, or certainly we could. This was around the time when John Brennan’s CIA hacked into the computers of Senator Dianne Feinstein’s people, who were investigating CIA torture activities during the so-called War on Terror. And I was struck by the following: Dianne Feinstein was extremely angry when she learned that the CIA was hacking into the computers of her staff and committee that was investigating torture. You would expect her to be angry. I was angry too. And she made a speech where she listed her grievances, and they were quite serious. That was a violation of Executive Order [12333]. It was a violation of the separation of powers. It’s a violation of the Fourth Amendment. Very serious allegations. And as I listened to the speech, I was like, oh, she’s really throwing down. I wonder what sort of punishment or redress or whatever she is going to call for. And her conclusion was, and therefore, I demand an apology. And I was struck by that. What does that mean? These are crimes you’ve just articulated. You’ve accused John Brennan and the CIA of committing quite serious crimes, and you’re demanding an apology. So the article that I wrote was essentially almost a precursor, although I didn’t realize it at the time, for the sorts of themes I’m dealing with in the new novel, The System. How I compared the behavior of Dianne Feinstein, John Brennan, and our other rulers to something that I remember from The Godfather, the book and the movie, where Michael Corleone initially suggests that, okay, I know how to deal with this problem we’re having where our enemy is being protected by a New York police captain: we’ll kill the police captain. And the family consigliere, Tom Hagen, says, Michael, we can’t kill a police captain; the Corleone family would be outcast. What he’s saying, essentially, is that would be going too far, that the violation of the rules and the rest of the system of which we are a part would turn against us if we did that. And Dianne Feinstein, it was clear to me, had a similar notion. None of these people think of themselves as crime families, although I think it’s useful to use crime as a rubric for understanding the way our rulers operate. But she did recognize that if she went too far, it would create a problem with her, with other players—other families within the system of which she was a part—and where her power was derived from. So instead, she fired the equivalent of a shot across the bow. What she said was, hey, you other families, either you straighten this guy out and get him to back off because he’s overstepped, or I will start creating real problems. And then what happened is other players within the system went to John Brennan and said, John, we know she can get a little crazy, but you have to admit you overstepped a little bit. They had to have a sit-down. You’ve got to apologize—all she’s asking for is an apology. All right, you’ve got to back off, and then we can get back to business. And that’s how this was handled. So I never forgot that. And as I said, it became the basis, in some ways, for the current novel. This is a better way of understanding how our system really operates. There are implicit rules. Fights start to break out, but the biggest ones are settled internally so that the system can get back to the business of ruling. You famously do a hell of a lot of research for your novels, and you’re one of the only novelists whose stories contain endnotes. Even though this is fiction, there are sources. And also, you have this wonderful page on your website where you correct mistakes. People write in and go, in this city, if you’re looking at this building, you’re not facing the southwest; you’re facing the southeast. And you’re like, well, I’ll go change it. You strive for as much accuracy as you can get, given that you’re telling a fictional story. And so, presumably, one of the things you had to do in this book is work out for yourself, to the extent that there were gaps in your perceived knowledge of how Washington actually works, what are the things that are just clichés versus what reality would actually be like in this situation? And I think in so doing, some of the conclusions that you’ve come to and the world of the book are going to surprise some people who might share your politics but not quite have reached that understanding of how this really works in the world. Let me just give a specific example. So if people expect that the powerful will be sinister behind the scenes, one of the things that might come as a surprise is that, throughout the novel, behind the scenes there’s such cordiality. People don’t necessarily curse and shout at you. And I think that’s one of the things that your protagonist, Velez, is surprised by. There are a couple of moments where she’s like, wait, you’re not mad? You seem weirdly friendly. This is all smiles. It’s not like there are smiles in public, and then behind the scenes, everyone is really nasty. That’s not how it works. No. And in fact, one of the epigraphs—there are 63 chapters in the book, and each one is introduced by an epigraph. I love this stuff, and you could tell I didn’t go out and search for this. I’ve just been collecting them for years because I like them. And then at some point I thought, oh, look at that, I can actually use an epigraph for each chapter in the book. One of them is from former congressman Justin Amash. I don’t remember it verbatim, but what he said is, you see fighting of the kind we’ve been talking about, but it’s Kabuki fighting. It’s theatrics. He said, when they turn off the cameras, these people are all friends. They understand it’s a show. It’s just a show. It’s like pro wrestling or something like that. And in fact—it’s a separate topic, but I think part of Trump’s success is recognizing that politics is a kind of show business, akin to professional wrestling, where it’s not real. I think the word is “kayfabe,” where there’s a heel and a hero. People get caught up in this stuff, but none of it is real. None of it is genuinely felt. So yes, that’s one of the things I try to depict in the book. It seems like these are cage death matches, but fundamentally, these people are cooperating, where their areas of cooperation are vast and their areas of actual conflict are very narrow. It’s just that, again, we tend to focus on conflict and fighting—we notice it more—where there’s bipartisan consensus on, for example, how we need to spend on the military. And the difference would be, should it be $950 billion this year, or should we make it an even trillion? That’s not a real difference when you consider all the other actual possibilities out there. This is Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent. How do you narrow choice to a degree that it doesn’t even really matter anymore, and yet people think it’s a real choice? Again, I don’t like to call these things two parties. I think they’re better understood as two wings of the same party, the duopoly. I think that’s just a better way to understand at least partisan politics in America. And then how is power actually, really exercised? That’s a much broader question having to do with Wall Street, Silicon Valley, the Pentagon—what’s often called the military-industrial complex—the energy sector, the media, things like that. This is where power really lies in America, not so much with the politicians. It becomes evident in reading this novel that clearly you’ve thought a lot about, how does it actually work? It’s not that someone comes to you with a briefcase full of $100 bills and hands it to you, and then the congressperson takes the briefcase and votes for the bill. And to explore that dynamic, you’ve built the story of someone who—not to diminish the size of your capacious imagination, but I think that as soon as people read the basic facts of the story of Valeria Velez, they’re going to get a little ring of familiarity. Clearly, to some degree, she’s based on the story of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, to the point where she’s Latina, a bartender, goes there to try and change the system, and 30 years old. So tell me, what is it about that kind of story, the story that you see in AOC—that kind of story about that kind of character going to Congress—that could illuminate some important things about how this system worked? I should start by saying that when I do interviews like this, when I talk about the politics of the book in public, I’m always a little shy about pointing to actual individuals. I’m going to, but I just want to tell you why I’m a little shy about talking about actual people. We’re just wired in such a way that we’re inherently, innately tribal, and we just connect to humans in a way that’s not necessarily helpful. So Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: whether you love or hate her, immediately, whatever I might have to say is going to light up your amygdala if you don’t agree, and you’ll have a defensive reaction. And I’m not interested in that. I’m trying to persuade, or at least to get people to be open to another way of looking at things. I’m not trying to put anybody down or anybody’s beliefs down. I could be wrong about just about anything. But all that said, I find AOC very interesting. I first encountered her because Glenn Greenwald interviewed her on his show. I forget what his show was. Maybe it was still called System Update. It was when he was with the Intercept. He learned about AOC because Ryan Grim had—I don’t know how she came to Ryan’s attention. Ryan was the Intercept’s Washington bureau chief, so he just knew about what’s going on in DC, and he recommended it to Glenn. He said, I think you want to interview this person. She’s quite interesting, and she’s taking on Joe Crowley, a 10-term corporatist incumbent. Nobody thinks she has a shot, but I know a little bit about her, and I find her quite interesting. So Glenn interviewed her. I followed Ryan at the Intercept, and I followed Glenn. So I watched this interview of AOC, and I have to admit, I was really impressed. She’s the best speaker I’ve ever seen live, by the way. Yes. I think she sometimes overdoes what I’d call the code-switching a little bit, but that might be personal preference. But she’s very, very talented. I totally agree. A natural, especially her social media game. It’s next level. She’s great. She’s obviously a remarkably talented person. She’s smart, articulate, and charismatic. Again, if you don’t like her, you don’t like her. These are just idiosyncratic reactions. It doesn’t really matter. But again, I was impressed. I was impressed by what she was saying and the sorts of values that she seemed to have. And this happens to me every time I start believing in a politician. When am I going to figure it out? I don’t know. But I was like, wow, this is great. I’m really impressed. Subsequently, following her trajectory from rebel firebrand outsider, bane of Nancy Pelosi and all that, to Democratic insider. And I think it was the New York Times that described the progression this way, in flattering terms. What you could read is she’s been tamed; she’s been gentled. She’s part of the system now. And you could argue, if I were writing a nonfiction story of what is the apotheosis, or the nadir, of AOC’s political trajectory, I would identify it as being last summer’s speech at the DNC, where she claimed that Kamala Harris was working tirelessly to achieve a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. And I remember wondering at that point, how do you cauterize your soul sufficiently to be able to say something like that? It’s quite a thing. And she went to that position from early on making the political mistake of saying, look, I don’t have that much to say about Israel and Hamas. She’s somewhat critical of the Israeli government, which is always refreshing in American politics. But she said, look, it’s not something I know that much about, so I’m a little reluctant. I actually always admire people who say, well, my opinion on this isn’t that strong because I don’t know that much about it. That seems quite reasonable to me. Anyway, on balance, I would say she’s been something of a disappointment. I don’t want to overstate. I think it’s foolish to put too much hope in any politician, but I have thought a lot about what happens to someone like her, and I try to depict this in the book with regard to Valeria Velez’s journey through power in America. I could see where it starts. If you think about it, I want to give AOC her due as a novelist. This is just my interpretation. I’m not psychic, and I could be wrong, and other people might not agree, but I think she probably did start with genuinely held convictions. She wanted to get into politics to achieve her genuine ideals. Whether you agree with those ideals or not isn’t material to the point. And what she discovered early on is that once you’re in the system, if you want to get anything done, you have to find a way to use the system to wield the levers of power available in the system. And this is going to require compromise. The more power you want to accrue, the more compromise you’re going to have to put up with. At some point, the rationalizations will pile up to a degree that you might have lost sight of your ideals entirely. And to move this into [the fictional] realm, in the very first chapter is the victory party in Lancaster, California, California’s 27th district, where against all odds, she has just defeated her 10-term corporatist incumbent, Fillian Dunne. And so it’s a big party, but within minutes, what she learns is that the Pentagon is moving the next-generation air dominance fighter jet program out of her district, Palmdale. This is where Air Force Plant 42 is located. They’re moving the program to Fort Worth, which happens all the time. Valeria’s constituents are out of work overnight. Valeria ran on a campaign of, we’re going to stop stuffing them all of the military machine, implement a universal basic income, and return power to the people. Immediately, the Pentagon’s like, all right, good luck with all that. We’re going to put 5,000 of your constituents out of work. See how you like us now. And she recognizes immediately that if she lets this happen, she’s only going to be a one-term congresswoman. If she doesn’t fight for those jobs, then those 5,000 constituents won’t just not vote for her next time, they’ll campaign against her, and they’ll vote for her opponent. She’ll never be reelected if she lets this happen. So what do you do in a situation like this? The rationalizations are right there for you. Not only will she not be able to get anything done in Congress as a one-term congresswoman, but she’ll also be an object lesson for what happens if you take on the military-industrial complex. She’ll have been worse than useless. So the rationalizations start kicking in. Now imagine 10 years of rationalizations like that as you get closer and closer to the next rung of power. What’s going to be left of you at the end? And this is a question that interests me on a human level. And really it’s the human level that makes novels work. If you don’t have that, then you should write something else. What happens to a person as that person interacts, the way Valeria Velez is interacting, with power? So as far as AOC goes, what I would say is, if you love AOC or you hate her, don’t worry. This isn’t a novel about AOC. Certainly the character was inspired by AOC, but that’s where the similarities end. So AOC’s trajectory is, as you say, deeply fascinating. You could tell two stories. One story is the sympathetic story, which says, okay, this is someone who is actually learning how the system works and how to operate effectively within it, which is the story, as you say, that the New York Times told. And then you can tell the story that a progressive supporter of AOC might have, which is, this is the co-optation process that occurs. And in your endnotes, you cite Ryan Grim’s wonderful book on the Squad, and he got kind of the inside story here. And it is, in fact, the case that as soon as she gets into power, she comes in with this staff that’s very confrontational, and they’re all ready to take on Pelosi. She joins the Sunrise Movement and their occupation of Pelosi’s office. And then it rapidly becomes clear that Nancy Pelosi has a lot of power, and that if you start tangling with Nancy Pelosi and the leading Democrats, they will just ensure that you get nothing—that you are never the head of a committee, that you never get to pass any legislation. If you piss them off too much, they will fund your next primary opponent, and you will be out of office. And AOC has this moment where she purges her staff of some of the more confrontational people who are picking fights with the Democratic leadership. And you mentioned that moment at the DNC, which is, I agree, a real low point, because it’s an outright lie. They weren’t actually trying to facilitate a ceasefire. They were, in fact, blocking a ceasefire at the UN, vetoing it repeatedly, and Kamala Harris seemed fine with that. And then AOC and Bernie Sanders were two of the last holdouts supporting Biden when it was very clear that Biden wasn’t a viable candidate. And that was because they had seen how power works, and they thought to themselves, well, if Biden’s not going to go, we want to be the people who stuck by him, and then he’s going to be in debt to the progressive wing of the party for sticking by him. He was ultimately forced out, so that gamble didn’t pay off, but you could see how the gamble worked. But what you’re doing here is you are, as you say, setting aside one’s judgment about that process. You are trying to understand that process. It is not that someone comes in and they instantly shed their principles. It is not that someone comes in and they are bribed or their idealism evaporates overnight. It is a process. What you’re doing here is a work of political sociology. Yes, thank you. That’s a nice way to put it. It’s a nice compliment, and I think that’s a perfect description. Again, as a novelist, the thing that interests me most is the human experience. What makes us human? What makes our lives have meaning or not have meaning? What is life itself to humans? That’s all the stuff that interests me most. To “the humans,” as one of your characters might say. Thanks for saying that. It’s funny, because I do that myself. I like to refer to them as “the humans” because it gives me some distance. And this is another Chomsky thing, looking at America the way a Martian would look at America. I thought of Chomsky’s Martian when Monty was speaking. It’s funny. One of the lovely things about being a novelist is what gets caught in the weird filter of your brain. Because all the time there’s just something that catches in there. The Martian thing is just super useful. I guess you could call it a thought experiment, or a framework, that everybody should use. You don’t have to be a novelist or anything like that. I try very hard to do this. Am I successful? Who can say for sure? In fact, I once wrote an article for Boing Boing where I had a conversation with a Martian, and I was trying to explain to the Martian why American violence is good. This is what you and Noam Chomsky did at length in your book, The Myth of American Idealism. It’s a myth, but if you’re in it—if you’re American, if this is your tribe, if you’re in the in-group—it’s very hard to step outside this thing. And I would just mention, for anybody who’s interested, one of the best frameworks I’ve ever come across for understanding “the humans” is something called the fundamental attribution error. You can Google it if you don’t know what it is, but basically it’s this: the fundamental attribution error is the notion that when I do something good, it’s because I’m a good person—I’m innately good, I have good character—and if I do something bad, that was a mistake or a screw-up or whatever, but no reflection on my innate character. But the opposite framework gets applied to other people, people I don’t like, out-group people. If an out-group person I don’t like does something good, then I attribute it as, he must have done it for bad reasons. He’s still a bad person. I’ll acknowledge there might have been some good that came out of this one act, but he’s still a bad person who is probably acting for bad reasons. And if the bad person, the person I don’t like, does a bad thing, then I say, see, I told you, it’s a bad person. So you could say we judge ourselves by our good intentions no matter what we do, and we judge others, people we don’t like, by their bad intentions no matter what they do. And to get out of this, you’ve got to think, how would a Martian see this? So I was talking to this Martian for the article in Boing Boing and saying, ISIS is terrible, just as one example. I’m like, they burn people alive. It’s sick. It’s barbaric. And the Martian was saying, but didn’t you Americans yourselves not invent napalm? Napalm, which means sodium palmitate—you mix gasoline with a substance that turns it into a jelly, and it clings to human skin and causes horrific burns. And I was like, well, but that was a long time ago. That was Vietnam. And then the Martian says, but do you Americans yourselves not have a missile that you call a Hellfire missile? You’ve actually named it to celebrate its burning effect. It’s fire. It is a thermobaric weapon. “Thermo” is the Greek for heat, and “baric” means pressure. It produces a heat pressure wave of such intensity that it peels the skin off humans, even the ones it doesn’t blow to bits. And you celebrate this effect by calling it a Hellfire missile. And I was like, the Martian was really beginning to stymie me. So if you want to see your own culture, your own in-group, a little more clearly, you have to set yourself outside your own culture’s framework, or else you’ll never be able to see things accurately. So that’s Monty Cranston, my spinmeister savant, who refers to humans as “the humans.” He’s like dark Chomsky. He’s like if Chomsky had gone into PR for manufacturing consent because he knows how to do manufacturing consent. He understands these things deeply, and he’s somewhat amoral in the sense that he just knows how things work. At one point, he’s even thinking to himself that he doesn’t really understand individual humans, but he understands “the humans.” And as he puts it, he doesn’t see trees very well, but he can see forests. He thinks to himself he knows how it operates and how you manipulate the operating system with language, for example. Monty Cranston is, in some ways, my Greek chorus, because there are things going on, and it’s just a lovely plot device to have him. And for me, it’s extremely funny. He’ll point out something that’s really going on in the story. And just one example, he’s talking about how he told the Pentagon, don’t call it the next-generation air dominance program. They didn’t listen to him. He said, call it the next-generation air defense program. Defense is a good word. It’s why they renamed the War Department the Defense Department in 1947. Who can quarrel with defense? We all need to defend ourselves. War is a bit of a different matter. So he said, dominance isn’t good. People don’t really like dominance. And in fact, if you listen to our leaders and read Raytheon brochures and stuff, dominance is just a huge part of our culture, at least today. I had to stop, because I don’t want the footnotes to be taken over—to be dominated by—examples of the use of domination in our culture. But it is fascinating how prevalent this notion is that we need to dominate other countries and dominate the world, dominate the battle space—all these things that we need to dominate. If the Chinese ever talked about domination and dominating the way we do, we would completely freak out. And by the way, this is a quick example of what I’m talking about. We have to think like a Martian. You have to get outside your own skin. Because we don’t really think anything of this. We’re like, domination, it’s all good. Well, how would you feel if China, or some other adversarial power—pure power—were talking about dominating you? Would you think that’s okay, or would you find it threatening? How do you think the Chinese feel when we go on about domination? We’re talking there about Monty Cranston, who is a specialist in euphemisms, in massaging the truth—a spinmeister, as you say. And a couple of your epigraphs to chapters are from George Orwell. In the endnotes, I think you say that “Politics and the English Language” is the text that you would assign students if you could assign them one thing to help them understand. And, of course, Orwell’s whole essay is concerned with the use of euphemisms, and how the way we talk influences how we think and what we understand. And he talks about—he talks then, because it wasn’t new, certainly—how ethnic cleansing could be justified as just a “population transfer.” And reading that today, it doesn’t seem to have dated very much. It’s just new euphemisms. So tell us a little bit more about how the way people talk about things helps them in the process of that rationalization, because you’re exploring how people rationalize being part of this system. Yes, well, we already talked about, in fact, a couple of the big ones. Probably the biggest is the replacement of the word “military,” certainly the word “war,” but also the word “military” with the word “defense.” It’s everywhere. And, in fact, every now and then I’ll tweet to a left-leaning journalist, would it make sense to stop calling this defense spending or defense budgets and just start calling it military spending and military budgets? I think military is a much more neutral term. It interests me that the more accurate terminology here would be to say, for example, the U.S. government is now going to allocate a trillion taxpayer dollars to the military. That’s where it’s going. Defense is unclear. I actually don’t think it’s for defense. I don’t think anybody needs this level of money for defense. It’s nuts. But defense is an alleged intention. It’s actually going to the military. Why don’t you call it what it actually is? Well, because it’s propaganda. That would be one instance, and another one that’s been around for most of my adult lifetime, as far as I know, is the word “intervention” as a preferred term to describe America’s invasions and bombing campaigns and occupations, that sort of thing. If you think about it, “intervention” is a fairly friendly word. It’s something you would do with a friend who’s developed an alcohol or other drug problem. Get the family together. Someone needs to the pull the parties apart. They started it. We don’t start stuff. We just intervene. Exactly. To help, in our beneficent way, because our intentions are always good. So “intervention” is another one that that consistently interests me, and there are so many others. The use of the phrase “enhanced interrogation techniques” rather than torture. And I remember Chris Hayes saying—and I wouldn’t call myself a fan of Chris Hayes exactly, although maybe he’s doing the best you can do if you work for MSNBC—this is like calling rape nonconsensual sexual intercourse. It’s just like, what are you obscuring here? That was another one that’s quite obvious that I find pretty disturbing. I think there’s some reference to another one I came across in the book, the “surge” in Iraq. When the surge was announced, that’s another one that I thought about. Why the “surge?” Here’s the thing you’ll see in the book, and that I always imagine: these things are presented, and we don’t really think about where they came from. I remember when the surge was announced; the natural word, the organic one, the one that would be on the top shelf of your mind, most easily acceptable, I think, will be the tried and true “escalation.” That’s what we’re doing. We’re sending 30,000 new troops into this war. We’re escalating. That’s just what it would obviously be called. And I can imagine the marketing meeting. And again, I think the way to understand these things is to think about a marketing meeting. They’ve got a product that needs to be packaged and be positioned in the marketplace, and the brand name and the product name are going to be very important. So somebody said, all right, we’re going to have 30,000—we will write the speech for the President, and he’s going to say, we need to have an escalation. And then somebody said, no, that’s not good. Well, can we call it a temporary escalation? No good. Everybody’s going to think Vietnam—it’s open-ended, it’s a quagmire. And they tried a few different product names, and then somebody said, I got it. Bear with me here. Listen: the surge. Think about the surge. What does that conjure? The surge: the ocean tide surging up onto the beach. And what happens when the ocean surges onto the beach? What happens right afterward? It goes back out to the ocean. It’s temporary, and it might even clean up some of the detritus—some of the seaweed and shells, whatever’s on the beach—just sweeps it back into the ocean and cleans off the beach. It comes in, and then it goes out. And everyone said, oh, I like it. This novel is so rich with different themes. We talked there about euphemisms, about idealism meeting the realities of power. The media is covered in the book. People will see echoes of Julian Assange and Edward Snowden in parts of parts of it. But one theme that I wanted to discuss with you was, you cite at one point Dr. Strangelove. And I’ve written an article about Dr. Strangelove. One of the things I think that film captures so well is how things in a military context that are objectively insane and suicidal can come to seem rational and necessary. You have a Curtis LeMay-like character, and part of the book is about the U.S. developing new capacities for AI-controlled nuclear weapons, which is something that, if you think about it for a minute, is dystopian and horrifying. And you note in the endnotes that after you wrote the book, the very capacities that you were talking about are, in fact, under serious consideration by the U.S. government. One of the things that you explore in the book is that when everything we do is done to beat China to it—because if we don’t do it, they’ll do it first—and if it’s all for our national defense, we can end up rationalizing and justifying things that at first glance seem totally ludicrous and homicidal madness. Yes, that’s another thing that interests me. Akin to what we’re talking about, what happens to an idealistic politician who enters the system and starts compromising and rationalizing and getting closer to accruing more and more power as a result? What happens if you’re in an environment where these things are discussed in a way, viewed in a way, that ordinary people just wouldn’t understand? This is a moment I enjoy in the book. I don’t want to spoil anything. I will just say that Lance Thaddeus, my Julian Assange character, I find him hilarious in how he’s he’s almost driven crazy by the shit he is uncovering, and what he says about the notion of combining nuclear command and control with artificial intelligence, the person he’s talking to says, this can’t be true. And he says, how could it not be true? If a species is crazy enough to develop one potential extinction event technology—nuclear weapons—and then another one—artificial intelligence—how could they not try to combine them? What’s the worst that can happen? This is two great tastes that taste great together. And he’s just riffing on this. He’s like, where do new technologies always get deployed first? The porn industry and war, always. Sex and death, Eros and Thanatos. So of course, they’re putting these two things together. And I wrote this before I came across that article, and then I came across the article, and I’m like, yes, the military is really doing this. Of course, they are. Thaddeus was right. So it’s an interesting question: what happens to the people inside these institutions? And some of them have come forward, by the way. For anybody who’s interested in this, and it’s a bit depressing to read, or even worse than depressing, Annie Jacobsen has a book that must have come out a year ago, I think. You know what I'm talking about: Nuclear War: A Scenario. And it’s just a phenomenal book, albeit these sorts of things keep you up at night. It’s a hard read. It’s a hard read. It’s a very hard read. And one of the things she talks about is one of the guys who was, I think, involved in the hydrogen bomb project, and he was struck by how antiseptic it all became—throw weights and yields and blast radiuses and how many millions of people would be killed instantly, and how many would die later. People were just talking about it as though they were, I don’t know, talking about traffic patterns using spreadsheets. And I think the human incentives when you’re inside a system are to adopt the rules of that system. And this is, of course, true for tribes too. We’re wired pretty well to understand what the tribes expect, what they’ll tolerate, and what they'll reject and punish, and we start trying to conform to the expected behavior. That’s just part of “the humans,” and the only defense I know is to try to be as non-tribal as you can be, to try to be aware of the phenomenon. I have to say, if anybody's interested in this topic, there’s a guy I know named Paul Graham, and he writes some of the best essays I’ve ever read. One of them is called “Keep Your Identity Small.” I remember first reading it years ago, and I hadn’t articulated it the way Paul does. He writes terrific essays, I would say Current Affairs-level quality writing. “Keep Your Identity Small”—it has some very good advice. Once you start to identify with an in-group, a tribe, or whatever, it motivates you, whether you realize it or not, to stop dispassionately trying to get the most accurate understanding you can, and defending the in-group becomes your primary motivation. And that’s a dangerous thing if you prize accuracy. Daniel Ellsberg, who worked as a nuclear war planner at the RAND Corporation in the early ’60s, in his book The Doomsday Machine, recounts seeing this document that was for the President’s eyes only. And on the document was the plan for all-out nuclear war against the Soviet Union. It tracked the number of expected deaths, and it was 300 million within about a month. And he recalls his reaction was that this is a plan for a genocide that would dwarf the Holocaust. He says something like, this shouldn’t refer to anything that is real in the world. This should be in the realm of fiction. And knowing that it’s a real plan and that the weapons are real was so disturbing to him. And he felt like the sane person in a world that had just gone completely insane, but within this institution, somehow a logic has been constructed whereby these things made sense. Yes, I think if you think that deeply inside the box and forget everything else you know, then it starts to seem to make sense. I think that might be when they came up with the term “omnicide.” I might be wrong, but genocide wasn’t enough to describe what was in these documents. And by the way, this is the thing: as I get older, I hope I learn how to better persuade people. What are better tools of persuasion? I try not to just directly get people to conclude things. Instead, I try to give them what I think is an accurate and useful framework, and then they can plug in their own values. On this kind of stuff, what I would say is, a lot of times I think the U.S. government is doing something that, to me, is crazy, or at least it sounds crazy. And many times people will say, that’s crazy, they would never do that. And what I say is, well, if you think about it, any country, any humans having control of nuclear weapons, that is already crazy. We’re just so used to it that it doesn’t really seem crazy anymore. But it’s crazy that we would build and deploy potentially species-ending technology. So this is a version of the Dunning-Kruger phenomenon where you have some expertise in a certain area, and you read an article in the newspaper, and because of your expertise, you realize this article is just filled with inaccuracies, errors—it’s bullshit. And then you turn the page to the next article, which is on a topic you don’t know that much about, and you’re back to thinking that everything you’re reading in the newspaper must be true. You don’t really learn the lesson that if X is bullshit, Y might be bullshit too. So when I look at these things, I’m like, look, if the U.S. government is willing to do an extremely crazy thing, then why do you think it would only be crazy thing X, but they would never do crazy thing Y? They do crazy things. We know this. Now it’s proven. So it’s not impossible that crazy thing Y is also on the table. But like I said, because you’re a novelist, one of the nice things about doing this through the medium of a novel is that you really get to think, okay, but what does this thing that looks crazy look like on the inside to the people who are “the humans?” Because every system is ultimately, at its base, made of people. Those people have emotions, they have desires, and they have reasoning processes. So what is going on among those different people? From the outside, we might just see, well, AOC was inspiring at point one, and at point two, she’s doing things that seem to me to be disappointing, but what is actually going on in the mind of someone that could take them from from point one to point two? Which is why I say that this has value as a piece of sociology as well as a novel, because it’s really important if we’re going to dismantle a system of power to understand, what are the different pressures? And they go beyond legal pressure or financial pressure to emotion. One of the things I like in the book is the way you weave in people’s personal relationships as being really important. You’re not just writing a story that is a pure political drama. Thank you. There’s no novel that I would say is easy to write. I don’t want to overstate. It’s not like digging a ditch, but really, it takes a certain degree of discipline, and it’s not always fun. But it’s rewarding because it combines so many of my interests. And again, anybody who looks at the epigraphs, footnotes, and influential works listed at the end of the book is going to see that I am, you could argue, obsessed—I think obsessed may be too strong a word, but I wouldn’t get in an argument about it. I’m very interested in political stuff. If I could go back in time, I think journalism is what I would have started with instead of law. And probably, I like to think I would have wound up as a novelist anyway. So this sort of stuff really interests me, but storytelling and stories interest me as well. Obviously, I have a bit of a knack. I hope I do. I think I do. I suck at a lot of things, but I’m a pretty good storyteller. And so to be able to use that one tool—I can tell a story—but to bring the politics in too, I’m always thinking about these things. Sometimes people say, what happened to this or that journalist? And in my experience, often nothing happened. You changed. The zeitgeist changed. Glenn Greenwald, to me, is, by the way, the premier example of this. I’ve been following the guy, I don’t know, since he had a blog called Unclaimed Territory—close to 20 years ago, something like that. And I don’t see a lot of difference in his position. Some differences, as you would expect for anyone who’s been spending the last couple of decades writing on politics. But basically, he’s been against war and censorship. He hates hypocrisy. I see consistency there, but the left has changed a lot in the intervening years. I’m old enough to remember when the left was anti-war, or what was called the left—whatever. And again, censorship, and there have been dramatic changes in that regard. So if you’ve changed, and you look at the person who hasn’t changed, and you say, hey, whatever happened to you? But that is something I think about a lot when I see someone who has changed. We’re talking about AOC. It really intrigues me what happened there. I don’t think most people are bad. I think it’s lazy thinking to say, that’s a bad person. And I think it’s actually dangerous in some ways to think that way because it gives you a false sense of immunity. Oh, that could never happen to me. That’s right. Evil people do evil things; good people don’t do evil things. Exactly. And this keeps coming up—not on purpose, and I don’t benefit from it unless it helps other people. I just get a good feeling from that. But in the various interviews I’ve been doing in connection with the release of the book, I’ve been mentioning this wonderful short YouTube video called “Are we the baddies?” Oh, yes, fantastic. I love this. Mitchell and Webb. It’s genius. I don’t know those guys. This is the only thing I’ve ever seen. For anyone who doesn’t know it, you can just find it. Google, “Are we the baddies?” It’s a short skit. It’s two Nazis on the Eastern Front in World War Two, and one of them has this nagging sense that he can’t seem to shake. And he says, “I keep thinking, are we the baddies?” to the other Nazi. He starts presenting his evidence, and it keeps getting worse. Well, actually, I wrote a big article about the Vietnam War, and in one of the Vietnam War memoir testimonies that I read, a soldier in Vietnam recalled saying at one point or hearing one soldier say to another, we’re the redcoats, aren’t we? Which is an identical situation where he had this sudden revelation—using the stock of analogies that he had—and he went, wait a second, I’m the British in the American Revolution. It is extraordinary because, again, a Martian would say, how could you fail to see that? And I think the answer—and again, this is the kind of stuff that interests me as a novelist—is because we’re so wired to see ourselves as inherently good. I remember Ken Burns summed up his 10-part documentary on America’s war in Vietnam by describing it as a tragedy. And I think that’s very interesting. It’s hard for me to imagine that an American scholar would describe the Soviet Union’s invasion and occupation of Afghanistan as a tragedy. It’s just not a word we would use. We think of things like, the children sheltered in that school when the hurricane was bearing down on the town, and unfortunately, the tornado took a certain path and hit the school, and three children died. That’s a tragedy, no question. That’s what you call a tragedy. A human-planned intervention—an extremely improbable sequence of events that resulted in an invasion and occupation with half a million troops of a country that most Americans had never heard of, on the other side of the world—that’s not like a hurricane or a tornado or anything else. It’s not whatever else you might want to say; it’s not a tragedy. To call something like the Holocaust a tragedy would be very strange. It’s planned. We’re drawn into wars. We don’t wage wars. We’re drawn in. Always drawn in, sucked in, pulled in. But just to conclude here, Barry, I wanted to go back to what Praveen Tummalapalli was writing about in that article, “The Politics of Thrillers” in Current Affairs, where he discussed why your novels were such a surprising standout in a genre that’s kind of known for, not necessarily reactionary politics, but I think some of that good-versus-evil prevailing American mythology. Without necessarily disparaging particular successful writers in the genre, what is Praveen talking about in terms of the convention of the thriller genre, and how do you interpret what you’re doing as departing from that or trying something different? I think right-leaning tropes tend to lend themselves well to writing thrillers—action thrillers, political thrillers—in part because the things you can depict are inherently dramatic, cinematic. Take torture as a trope: compare the reality of torture and the propaganda of torture. Start with the propaganda. We’ve seen the scene in countless movies, if you’ve seen this kind of movie. The heroic guy puts the bad guy against the wall and maybe puts a gun under his neck or threatens him or something and says, tell me where the girl is! And the bad guy says, I'm not telling you. Tell me where the girl is! I'm not telling you. And then he’s like, okay, okay, copper. And it can be dramatic. If anyone is a fan of the movie LA Confidential—I wouldn’t call this any kind of rightist movie or anything like that. It certainly isn’t. It’s based on a James Ellroy novel. But there’s an admittedly great scene. It is riveting, with Russell Crowe playing Bud White, the damaged cop, who tortures a guy to give him information. He plays a game of Russian Roulette with the guy, until the guy tells him what he wants to know. It doesn’t make any sense. If the gun goes off, he’s going to blow the guy’s head off, and he’s not going to find out the information. It’s nuts, but it works cinematically, and it’s easy. It’s a good plot device. If you need some information, just have your hero torture the bad guy to get the information. So it lends itself well. Also, think about action thrillers. It’s mostly about heroes and villains. When they’re done well, they are. Die Hard is a great movie. It’s superbly well written. I could go on and on about that, but just leave that aside for the moment. If you like action movies, the writing does not get better than Die Hard. What’s it about, really? It’s about a hero, Bruce Willis, the cop who’s trapped in the building, barefoot and helpless, and the archvillain, Hans Gruber, played brilliantly by Alan Rickman—good and evil. That just lends itself to these kinds of stories. So it’s easy. That’s one thing you’ve got going on. And the other thing that’s going on, I think, is that it’s fair to say that historically, the right has been much better than the left—or at this point, right and left have gotten so topsy-turvy, I would say that the forces of propaganda and self-congratulation have traditionally been better than the forces of realism and self-reflection—at promoting favored narratives through fiction and drama. And so back in the day, you had a couple of thriller writers who—I haven’t been in touch with them in a while, but they’re good guys. I’m not trying to put anyone down. Brad Thor and Vince Flynn, both thriller writers and celebrated big New York Times bestsellers. Good guys. Vince Flynn died tragically young of cancer not that long ago, but he was a very nice guy. But I think it’s fair to say that their novels adhered to more traditional “we’re the good guys, they’re the bad guys; they hate us for our freedoms, America is a force for good in the world.” Not that the hero isn’t damaged, doesn’t have a wound or a ghost or whatever, but still, these novels promote a somewhat self-congratulatory, feel-good view of what America is and what it stands for in the world. Nobody who enjoys these novels, I think it’s fair to say, would be particularly receptive to a book like The Myth of American Idealism. It would just be like, what are you talking about? They’d be hostile with that. And you had some big voices on the right who were very happy to promote these novels. Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck, back in the day, heavily promoted these guys’ novels. Again, I’m not envious. I’m not complaining. I assume they genuinely loved the stories. But fiction is much more powerful, I think, than sometimes the forces of reason really understand. You were talking about “Politics and the English Language” earlier. It’s a fantastic essay. I think it’s maybe three pages. Every school child should read and reread this essay, and adults too. But what is Orwell best known for? Novels. 1984 and Animal Farm, particularly 1984. That’s what had the biggest impact. Fiction can can be a very powerful way of getting people to see the world, “the humans’” life, differently. And I just think the left hasn’t been very clever about promoting fiction that promotes the leftist point of view, or whatever you want to call it. The reality-based community hasn’t been very clever about this. And so people respond to incentives, and if you could get invited onto Rush Limbaugh’s show back in the day—he’s gone now—that’s a very big megaphone that’s going to be promoting your work. Whereas someone like me, I like to think that my stories are awesome—and of course, you shouldn’t take my word for it, but readers and reviewers seem to think the stories are great—but they’re more nuanced about the way power is presented. And you read a story like the new novel The System, and it’s just not that clear who are the heroes and villains. And you’ll make up your own mind; you’ll feel favorably disposed toward some characters and less so toward others. But this is not a story of heroes and villains. It’s a lot more complicated than that, because reality is complicated, and I think that’s something that’s more difficult to present in a traditional thriller setting than “we're the good guys, they’re the bad guys; we’re a force for the good in the world.” Sometimes we have to get our hands dirty with Jack Bauer. It’s more difficult, but somehow you pull it off. People might say that, well, the genre inherently doesn’t lend itself to this kind of complexity. But what’s cool is that you’ve managed this because you have a lot of readers who love your work. Somehow, you’ve managed to break the conventions a bit. I was totally honored to have The Myth of American Idealism, which I co-wrote with Noam Chomsky, in the endnotes. But then I was thinking, wow, not many people, as a percentage, read Chomsky books. They’re dry, they’re difficult, and they hurt to read because they’re long catalogs of atrocities. I get it. But you’ve managed to take, the analysis of Stephen Walt, John Mearsheimer, Jeffrey Sachs, Scott Horton, Noam Chomsky—these dissident thinkers—and you’ve managed to package it into a story that somehow doesn’t feel like it’s just beating you on the head with Chomsky’s ideas, where everyone is an obvious stand-in for something. There’s a level of human complexity and drama, and people have family lives, and people have doubts. So, congratulations on The System. Thank you very much. That’s a really nice compliment. This is fiction, but I don’t want it to be a fantasy, and I certainly don’t want it to be propaganda. I want everything I do to be as real as I can make it, with fictional characters dropped into functionally nonfictional settings and circumstances. And so I’m influenced by people like you, Current Affairs magazine, Chomsky, and all the other people you mentioned. All of these thinkers have shaped my worldview, and I want that worldview to be represented in the fictional worlds I create. That’s what I’m trying to do. Well, I hope other people will take up this challenge, because, as you say, there is room for more experimentation here. I hope that other fiction writers will consider doing the kind of thing you do here. It’s not obviously a “novel of ideas,” where you’re just having people have philosophical conversations back and forth. But as I say, there’s a ton of endnotes here. Smedley Butler and Chris Hedges and Machiavelli and Seymour Hersh are all in the endnotes. So just to give our readers and listeners one tiny bit more of encouragement—this is my non-spoiler spoiler—one thing that you will find out if you read the book is that if you’ve heard of the parliamentarian, the parliamentarian ends up having somewhat of a major role here. And it was one of my most delightful surprises, that the parliamentarian turned out to be really important. I thought that was so funny. Thank you for that. Transcript edited byPatrick Farnsworth.Nathan J. Robinson

Barry Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler

Robinson

Eisler