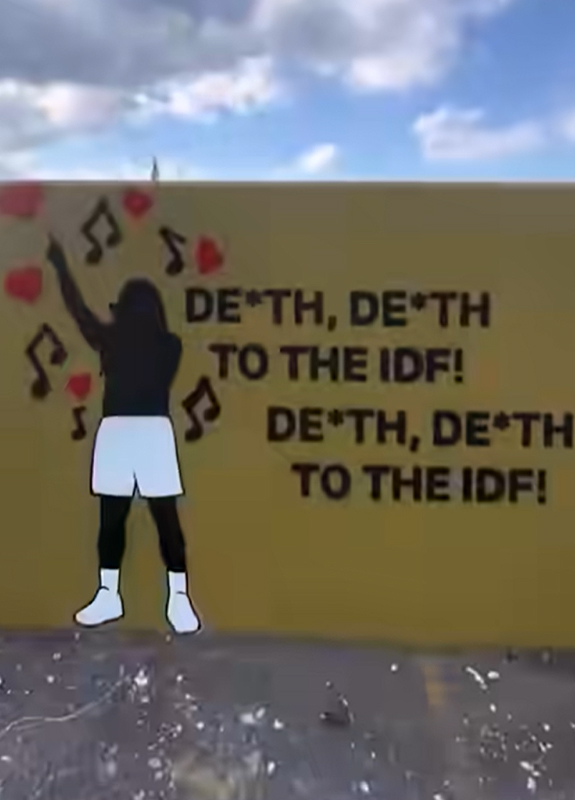

Where Most States Have an Army, Israel’s Army Has a State The Israel Defence Force (IDF) is the founder, enforcer and economic engine of Israel. The executive and legislature of "the only democracy in the Middle East" have always been dominated by senior military figures, and the military is the ideological foundation of the 21st-century ethnostate. The IDF integrates diverse Jewish identities and ethnic minorities into the state's religion: militarism. The military generates 20% of GDP - not counting the spin-off tech industry exporting the tools of digital apartheid - and furnishes Israelis with "free real estate" by defending West Bank Settlements. It's easy to see why former soldiers, who make up the vast majority of Israelis, have a huge ideological and material investment in the military, the ongoing occupation and the genocide in Gaza. This essay will lay out why shouting "Death to the IDF" is the only logical attitude of people who want a free Palestine. The mechanisms of governance established by the militia during that war crystallised into the modern Israeli State. However, unlike in many other cases of military capture, they did so with huge ‘democratic’ mandates. This is unsurprising due to the near-universal participation in the war by the Jewish population – 50% of all adult men directly fought either in the cleansing or in the battle to keep the land claimed in the Nakba. The General-Politician Pipeline The emergence of military rule in Israel is unusual because a free and vibrant political culture and democracy accompanied it. Of course, as noted above, full access to this democracy is only extended to Jews. Generals-turned-politicians dominate because militarism is the state religion: 5 of 12 prime ministers were senior officers, and their campaigns promise ‘security’ - a euphemism for perpetual, genocidal war - because that is incredibly popular. The War Economy: Israel’s Bloody GDP. The IDF's Engineering Corps builds roads for settlements, its Civil Administration oversees Palestinian land confiscations and its Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) regulates Gaza's economy down to calorie counts. Even in "private" sectors, the military holds stakes: Tzahal (IDF) Discount Stores dominate retail. At the same time, military-run farms control 40% of Israel's agricultural land. The result is an economy where every shekel flows through the IDF's hands, turning occupation into an extractive industry. No separation exists between military and market—the army is the market. The role of the IDF in expanding the borders of Israel via the illegal settler movement is vital for keeping the Israeli economy growing. Tel Aviv is amongst the least affordable cities on earth. The regular infusion of free real estate suppresses house prices and the cost of living, at least in settlements. As a result, average wages are artificially lowered and profits inflated. It's telling in this context that most people living in illegal settlements in the West Bank and Golan Heights are not religious zealots or even politically affiliated with the settler movement – they move there for bigger homes and a better quality of life. Veteran’s privilege Consider Yair Lapid, a one-time journalist for the IDF’s internal paper, who spun that into a journalistic career and later into a premiership. Even ‘liberal’ outlets like Haaretz are run by veterans like Aluf Benn, who frames apartheid as ‘policy debate.’ Climb the ranks by enforcing the siege, then cash in by selling the tools of repression. Israel’s ‘free press’ cheers when Gaza burns because they are cheering on their comrades (and kids). The tech sector is worse – every 4th Israeli tech CEO is a former intelligence officer. Alumni of Unit 8200 dominate Israel's tech sector and are vastly overrepresented in senior jobs in the US and UK Tech sectors. They repackage the tools of apartheid as ‘innovation’. NSO Group - founded by ex-Unit 8200 officers - tested Pegasus spyware on Palestinians before selling it to dictators who murdered Jamal Khashoggi. Waze's mapping AI was trained on stolen Palestinian land while aiding IDF operations. Rafael Advanced Systems perfected Iron Dome by bombing Gaza, then marketed it as "defensive tech." The business model is explicit. Elbit Systems’ drone surveillance tech, battle-tested in Gaza, now bolsters EU and US border patrol operations and smart fences, exporting Gaza’s siege logic to global borders. AnyVision's facial recognition, honed at West Bank checkpoints, was used to track BLM protesters in the US and UK. Tal Russo, a former IDF Southern Commander, joined Check Point’s board after overseeing the 2014 Gaza bombing that killed 2,200 Palestinians - a seamless transition from war crimes to cybersecurity profits. The Unit 8200 Alumni Association operates as a shadow investment network, funnelling military cash into startups. Google and Microsoft's Tel Aviv R&D centres launder occupation tech into consumer products. The message is clear - atrocity is just a bullet point on a CV. When every editor, CEO, and minister is a former comrade-in-arms, dissent becomes career suicide and support is incredibly lucrative. The IDF as "The People’s Army" Military service, and particularly combat experience, builds incredibly tight bonds. It also desensitises the Israeli public to violence and personally implicates most of them in some of the worst crimes of the last 75 years. What happens if the regime falls, and the population have to face the consequences of their actions as heavily armed teenage concentration camp guards? Of course, some soldiers do decry their crimes. See, for example, Breaking the Silence testimonies, where soldiers admit to atrocities. Yet the system persists. There is a cottage industry of such admissions - a genre called “Shoot then Cry” media, which is thriving globally. Why Palestinian Liberation Requires the Death of the IDF. The army materially enforces apartheid via checkpoints, home demolitions, the Gaza genocide and before that the blockade. But it also incites escalation. The political, media, and economic elite are ex-soldiers who think of themselves as such. Were the ‘conflict’ to end, the privileges that the elite enjoy and their ability to reproduce those privileges for their children - both nationally and globally - would fall apart. We can see that the IDF allows for ordinary working and middle-class Jewish Israelis to derive very real economic benefits from the occupation. The powerful military serves to provide cheaper homes, well-paying jobs and world-class social provision paid for by the international arms trade and direct foreign investment in killing Palestinian children. That benefit would dry up absent a permanent war or the military-state apparatus. Any Palestinian state alongside the IDF state would be constantly under threat because of these pressures. At the same time, the IDF exists in its current form precisely because it is structurally committed to apartheid. This means no Israeli state can be democratic, even in the liberal sense. If there is no excluded other, there is no ideological unity, no testing laboratory and no media-military-industrial elite. Israel must be de-Haganafied like East Germany was de-Nazified for anyone to see peace, let alone justice. ‘Death to the IDF’ means ‘Free Palestine’ It would be churlish to think that such a project would not be met by military force. Logically, this means supporting Palestinians exercising their rights to armed struggle, and supporting the military defeat of the IDF. Here in the UK, it means solidarity with refuseniks, Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions and direct and political action to resist militarism and isolate Israel. From the river to the sea, a liberated Palestine means a world without the IDF.

Israel is a militarised entity where the armed forces dominate politics, economics, and society. Palestinian liberation is impossible without its defeat.

The IDF created the State.

The IDF did not emerge from Israel. Rather, Israel emerged from the IDF - born in the ethnic cleansing of 1948 and sustained by perpetual war. Zionist militias such as Haganah, Irgun, Lehi, etc., became the IDF before Israel had a government or even a proto-state. Militia leaders such as Ben-Gurion, Dayan, and Rabin were warlords-turned-statesmen who were already months into the ethnic cleansing of Palestine before the declaration of Independence. They recognised that the only way to achieve their ethnostate was to kill and drive out the Palestinians. Plan Dalet, involving the expulsion of Palestinians and the massacres at Lydda, Tantura, Deir Yassin and others, was the proto-IDF’s blueprint for conquering their new state.

It may be tempting to argue that Israel’s ‘democracy’ is a façade on the basis that half its prime ministers and the majority of its presidents and its senior ministers are ex-senior officers. It looks like a military junta with extra steps. Policy appears to be dictated by the military. This, of course, is inaccurate; it’s a façade because Israel is an apartheid state where half the population the state rules over are non-citizens kept in concentration camps and Bantustans.

Israel’s economy doesn’t just serve the IDF; the IDF is the economy. Approximately 20% of its GDP is generated directly from the IDF and arms exports. The military also operates as a direct economic actor by controlling land seizures, infrastructure projects and labour markets. It also functions as the nation’s largest employment program. Approximately 18% of Israelis work in security-related sectors, with the IDF itself employing over 200,000 active soldiers and 50,000 civilian staff, making it the country's single largest employer. The military-industrial complex forms the core, with Elbit Systems, Rafael and Israel Aerospace Industries – specialising in Gaza-tested drones and missile systems sold globally - dominating the $12 billion annual arms trade.

Military service is the gatekeeper to economic mobility. Even mandatory National Service operates as a patronage network. This is especially true in ‘prestige’ units like Sayeret Matkal or Unit 8200 - the elite IDF Signals Intelligence and Cyberwarfare unit.

Mandatory conscription turns every Jewish Israeli into a stakeholder in apartheid, weaving militarism and Zionism into national identity. Historically, military service served as a de-Arabizing mechanism for Sephardi and Mizrahi immigrants, facilitating the integration of minority identities into the ideological state apparatus. Druze or Bedouin, for example, can demonstrate their value as citizens by volunteering for national service or by becoming professional soldiers. This is one of the only entry points into the Israeli ruling class for non-Jews.

As I have outlined above, the IDF is not just an army - it is the foundation of the settler-colonial project. Its dissolution, therefore, is non-negotiable for freedom.

When Zionists claim that “Death to the IDF means death to Israel”, they admit the truth - Israel cannot exist without its army of occupation and expansion. Still, we must not accept their rhetorical second step that killing off the IDF means killing Israeli Jews, or is in some sense antisemitic. Rather, it’s a call to dismantle their regime of privilege.

Organise!

Friday 11.7.2025