The author and economist explains why capitalism doesn’t make life better, why Trump is slapping tariffs on everyone, and how to understand money and power.

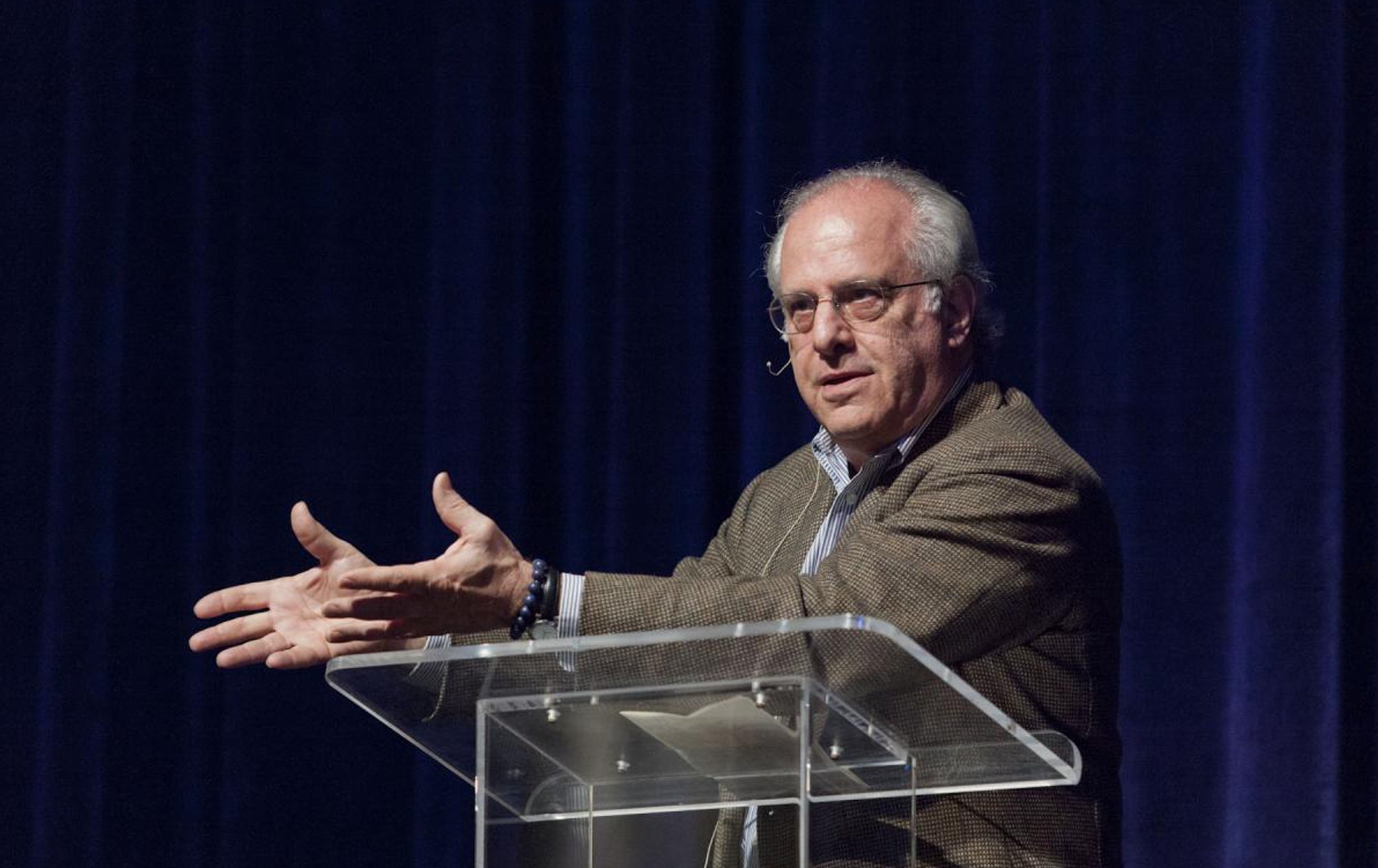

Professor Richard Wolff is the host of the weekly program Economic Update, co-founder of Democracy at Work, and the author of numerous books including Understanding Marxism, Understanding Socialism, Capitalism Hits the Fan, and The Sickness Is the System. He joins Current Affairs to explain how economics is deliberately taught in a way that confuses people and obscures the realities of power and exploitation. He dismantles the myth that capitalism delivers prosperity, showing instead how it generates instability, inequality, and crisis. Wolff also offers a sober analysis of America’s imperial decline, critiques Trump’s economic agenda, and exposes the economic lies behind anti-immigrant rhetoric. Many of your books have the word “understanding” in the title. You started as an academic economist, but you have in recent years dedicated yourself to helping ordinary people understand the often confusing and mysterious forces—the economic forces—that shape their lives. I wondered if we could perhaps start with some of what you are trying to get people to understand, some broad themes that come out. I’m sure you respect a lot of what ordinary workers perceive about the economy that perhaps many economists don’t perceive, but there has to be a great deal that ordinary people don’t understand about the economic world. So when you take someone who doesn’t really understand economics, how are you trying to open their eyes? What are you trying to show them? Well, the way I would answer that question is to say something unflattering about lawyers. Okay, I’m a lawyer, so be careful. Here’s a joke, and it goes like this: I give you $10 and in exchange, you deliver a pound of potatoes to me at a certain point in the future, and then that point arrives, and the potatoes don’t show up, and I make a complaint. I’ve been hurt, I’ve lost my money, and I have not gained the potatoes. Well, that should be a simple problem to resolve, and it is, in fact, a simple problem. However, lawyers have created layers upon layers of precedent and rulings and exceptions. And so it turns out that resolving this simple problem requires you to hire a translator to take the complexities of the law and reduce them back down to the simplicity of how they all began. And for that, of course, you need to hire a lawyer who will be able to do that translation, having gone to law school and learned about the first phase of the operation. Well, having made the joke about lawyers, let me now turn it on us, the economists. Please do. We do exactly the same thing. We take very basic, pretty simple ideas and run them through a special hamburger machine, and out comes gobbledygook—the material of textbooks and of classroom lectures—and the young people write it down in their notes and give it back to you on the exam. Then, when they try to apply the so-called learning of economics to the world around them, they find themselves lost. They can’t do it, and they revert, understandably, to what they learned because they don’t have any other vocabulary, basically. And so we end up with a population, and here I include not just the working class, but the media people, the academics, the politicians, the corporate leaders who have been to the same classes—I’ve taught them all, and I can assure you that they don’t understand it any better than the people they’re working with—which has, and I’m going to say this in a simple way, an extraordinarily low level of economic literacy. So you’re talking there about how the economic profession can take obvious features of ordinary reality that we can perceive without studying economics, that are hugely important to economic reality, and obscure them so that we no longer understand them. A specific example of that, which came to me while you were talking, would be the existence of power. Everyone understands in their workplace that their boss has the power to tell them what to do. The idea of bargaining power is fairly intelligible to people, and yet, as I understand the mainstream economic literature, for a long time, at least, power was very difficult to even fit into an understanding of how the economy works. One hundred percent correct, except you use the past tense, and you don’t need to. The present tense will do, it’ll cover the past, and that has not changed. Here’s a reality that everybody understands: When you go to work and take a job, there is a person somewhere who has the power to fire you. It’s indeed more or less the same person who had the power to hire you. You don’t have that power over that person, they have it over you. This is rather crucial because it means they are free to do things that might displease you in 10 different ways, but you have no such freedom. And you are living all the time with the absence of that freedom, and no amount of telling you that we live in a world of liberty and harmony and equality takes away the reality of what you know, even though you will say—particularly on the Fourth of July here in America, when we celebrate this nonsense—that you live in a land of freedom and democracy, when you do know such a thing, and you know that you do know such a thing. When I explain that in my classes, my students don’t rise up in objection. They look at me a little bit like puppies who have done something inappropriate on a rug. They understand exactly what happened here. As I take what you’re saying to mean, it’s that economics should perhaps start with the real world and build its theories and its knowledge based on what actually happened. But Milton Friedman made a famous argument that it is not, in fact, necessarily what economics should be. He had a famous defense of the unreality of economic models, saying that our models might not fit reality, and you can point out all the ways in which humans do not act like the famous homo economicus. But that doesn’t matter, because what matters is, as in physics, whether the models make sufficiently accurate predictions. He argued that, essentially, it was a red herring, or not a knock on economics, to say that their theories or their models weren’t realistic. You had to show that they didn’t work as predictors of what would actually happen in the world. Yes, the problem with poor Milton Friedman was that every prediction ever made has sooner or later not worked. That’s the reality: the reality in physics, it’s the reality in economics. No one predicted the crash of 2008, or let’s put it this way: I’m sure there were a few folks out there somewhere who did, but the whole of global capitalism crashed in 2008 and 2009. No one predicted that. The vast majority of models which I study and teach from had no clue. They didn’t have any clue before 1929 either. They didn’t have a clue about the pandemic of 2020. They don’t have a clue about Mr. Trump and his tariffs. They don’t have a clue, and they know that they don’t have a clue, but you can’t get a university position if you say that. And I say that as a person who has a university position. Well, but here, Professor Wolff, it’s my chance to give you a slight correction, which is: you say nobody predicted it, but you are a Marxist or Marxian, and the Marxists, because of their framework of capitalism as being deeply unstable, were the people who weren’t surprised at all by the meltdown of 2008-2009. Well, I don’t run away from the label of Marxist, but let me be self-critical as well. Among Marxists, we tell the following joke: We are very proud to have predicted 10 of the last four crises. Very important. I know that one. The point is, Marxism teaches you about—gives you an awareness of—the instabilities and the forces that make capitalism a remarkably unstable system. It does not tell you—and anyone who says otherwise is thinking in a mechanical way—when it’s going to happen. It doesn’t tell you how deep it’s going to cut. It doesn’t tell you how long it’s going to last. Those are all questions of the conditions and circumstances in which the downturn of capitalism happens. And by now, yes, we have some confidence. We have this institution here in the United States, partly private, partly governmental, called the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and one of the things they do—very establishment, in no way tarnished by any association with Marxism or any other terrible ideology—is they keep track of the economic fluctuations. And they have taught us what everybody knows in economic history, that wherever capitalism has settled down, on average, every four to seven years, it experiences a crash of one kind or another. Some are short and shallow. Others are long and deep. That varies all over the lot, and it’s only an average, but you will not find an exception to that situation. It is an unstable system, and because it happens every four to seven years, it means that those of us that are adults have already, at the time we begin thinking, lived through a bunch of them. Therefore, to deny that instability is a remarkable act of ideological misspecification. And I'm being as polite as I know how. You’ve talked there about how the identification of the inherent instability of capitalism is one of the advantages of a Marxist economic framework. But of course, it is still the case, as you indicated, that among those in your profession of economics, Marxism is a minority position, to say the least, still. And I wondered if you could expand on what you think it is that your fellow economists miss. They would see Marxism as discredited, as more religion than science, etc. They have all their criticisms. What are some other ways in which you think this Marxist lens on the economy opens our eyes to how it really works? Okay, let me choose one example of many. In the official canon—and I’m a product, I should tell you, of the elite education system of the United States. I went to Harvard, then I went to Stanford, and I finished my education at Yale. I’m like a poster boy for the elegant education. So I am reporting to you what I was taught in the 10 years I spent in that quasi-penal institution, those three in particular. Here’s what I was told: Capitalism is a wonderfully well articulated system, the greatest that the human mind has so far been able to construct, in which a partnership exists among the workers, the capitalists, and the landlords. Each of them contributes something. The capitalist distributes the capital; the worker, the labor; and the landlord, the land. And together with the land and the capital and the labor, we produce a wonderful basket of output, which is then shared among the contributors in proportion to what each has contributed. This is a lovely story. It can be rendered for a three-year-old. It sounds like something in a children’s picture book. Exactly. It is by, of, and for mental children who are entranced by this story, the way your three-year-old would be to learn about the chicken who discovered the squirrel. Okay, this is lovely. What’s Marxism? Marxism says, this is silliness. This is fantasy. This is the equivalent of saying, in a case of slavery, the master does what he contributes, let’s call it mastering, and the slave does what he contributes, labor, and maybe there’s a landlord in the story—why not?—and slavery is the wonderful coming together of the three. And since what the master does is so important, he gets a big share, and what the slave does is less important, he gets—you get it? It’s a story of decency, of fairness, of justice. The Marxists come along and say, are you crazy? The worker sells his ability to work. He sells eight hours a day. I’ll come at eight o’clock, I’ll stay until five o’clock in the afternoon, and you can tell me what to do, how to do, where to do, with what equipment, on what raw material, and at the end of the day, whatever I’ve poured into it—my creativity, my mind, my brains, my muscles—it belongs to you. You bought my power, but you get the result, and you spend that result once you sell it. You spend the results you get. In that story, you only hire me for one reason: that the value of what I add by my labor is greater than what you have to pay me to come there and do it. If there isn’t a difference, you won’t hire me. You understand that even if you didn’t go to business school, and I’ve taught in business schools, and that’s what we teach them. So it’s all a fair story. It’s a wonderful arrangement. That’s why it’s so successful. And the Marxist comes along and says, what you’re doing is telling a story whose whole purpose is to obfuscate what’s going on here. By the way, that’s why Marxists are a minority position. Because if you teach this to the working class, you know what happens? They get angry, just like you and I would if we were told that story. The story of Karl Marx himself is really quite inspiring in this respect. He comes to London as a poor immigrant, is looking out over 19th century industrial England and perceives, while this fairy story is being told as it was in the 19th century, as it is now. And he sees child labor, sees people’s bodies being destroyed in mines and factories, and determines to dedicate himself at the cost to his health, to his family—really suffers—to try and understand how this really works. Yes, he does. And you say it poetically, which I, by the way, being someone who has learned a great deal from Marx, feels an intellectual debt to Marx that I’m grateful for. I don’t mean a debt in the sense of a burden—it’s a debt I'm grateful in acknowledging. Yes, Marx lived in the London that Dickens described, and we know what he saw and lived through when he walked through the streets of London at that time. Here’s how I would put what he did, what he dedicated himself to—and I’ve studied Marx’s life, so I know a little bit about it. He was caught up, as was the whole generation in that early part of the 19th century—in this case, in France and Germany, because he comes from the border region between France and Germany—young people at that point in time, and in that part of the world, were absolutely enthralled by the French Revolution. The slogan “liberté, égalité, fraternité” was for them a spectacularly successful concentration of a new world. These are the people who thrilled to Beethoven symphonies because they were welcoming a new world, a post-feudalism that was better even than the Renaissance had been before. They felt carried forward, but they were also the first couple of generations after the French Revolution. So when Marx is an adult, a young man, he looks around London, sees the Dickensian world that it was at that time, just as you say, and he reasons to himself as follows: capitalism replaced feudalism, and it promised that replacement, getting rid of the Lord-serf relationship, and replacing it with the employer-employee relationship, would bring in “liberty, equality, and fraternity.” They meant that. They were sincere in seeing those as all coming together. And Marx’s conclusion, which shapes his life, is that you got capitalism, but you never got what was promised to go with it. There was no equality, there was no fraternity, and there was no liberty. And Marx, because he wasn’t just interested in bearing witness to this reality—after all, you didn’t need him to, Dickens did a better job of that anyway—what was necessary was to account for it. Why did capitalism, celebrated sincerely by people who wanted it to bring “liberty, equality, fraternity,” fail to do so? His job, his contribution, is he explains to us what it was about capitalism that prevented it from delivering what it had promised, and the critique is designed to answer that question. It’s not a critique made on its own ground for its own aesthetic appeal. It has, by the way, aesthetic appeal, but that’s not why he did it. And he was a very clever man. If you ever read Marx, you’ll know he’s quoting Dante and Shakespeare every other page. He’s a very well-educated European intellectual at the time. But his job was to show the answer to the question, why did capitalism not deliver on the promises of liberty, equality and fraternity? His answer is, because capitalism has within it the structural impediments that block it from doing so, so that if you want liberty, equality and fraternity, you’re going to have to go beyond capitalism because it cannot deliver on that promise. And by the way, I would argue, coming later, coming now, that it’s still as bereft of delivery on that promise as it ever was. And I’m sitting in Manhattan, surrounded by billionaires who are living less than a half a mile from some of the worst poverty I can show you on this planet. Now, we’ve been talking here about capitalism, and one thing that you said there was that capitalism replaced the lord-serf relationship of feudalism with the employer-employee relationship, and I think that’s important to dwell on, because one theme that comes up in your work is that people misunderstand what capitalism is. If you ask people to describe capitalism versus socialism, they might say capitalism is private property and markets, socialism is collectively owned property and a command economy. But you mentioned something that is central to your analysis of what capitalism is, that is to say, the nature of relationships within the workplace. So, can you help us clear up what you think are some misunderstandings of what capitalism is when we’re talking about it? I’m very glad you asked the question because it gives me a chance to say something that I think, like you just said, is core to what we’re talking about. Private property—let’s start with that. Private property is not unique to capitalism. It doesn’t belong in a definition of capitalism. I’ll take slavery as it existed in the American South before the Civil War: Did you have private slave plantations all over the place? Yes, you did. Did you have a market? Absolutely, you had a market for slaves, and you had a market for the products of slave labor. So the presence of a market and the presence of private property does not allow you to differentiate capitalism from slavery, for example, and for many other systems that I could show you, the same thing works. And to say that, for example, where there is collective property and where there isn’t the market as we understand it, we have something other than capitalism, I would argue, is equally out of order. It doesn’t really make any sense. I like to remind people that the ownership of a modern corporation is a collectivity of shareholders. They together own the corporation. It isn’t privately owned in the sense that usually is meant by private individuals. It is owned collectively. If you turn to the board of directors, the people who really make the core decisions, that turns out to be a collectivity as well. Usually, between 15 and 25 individuals comprise a capitalist corporate board of directors. So individuality isn’t a particularly definitive quality of capitalism. And let me take it another step. Some people like to think of socialism as when the government owns and operates enterprises, the way they did particularly in the Soviet Union, and the way half of the enterprises in China today are organized. And I would argue that’s another mistake. Marx never said that what gets rid of capitalism is if you remove the private individuals and substitute state officials. That would be a change— Monarchy would be socialism. Yes, it really is a bizarre idea. And I’ll show you that in the university, if you teach slavery, do you tell people that the state, in various slaveries, owns slaves? Of course you do, because that’s very well known in the historical record. Nobody in their right mind would suggest you no longer had slavery because the government coexisted with private slave owners, and the same is true of feudal plantations. So why did we develop in the West this bizarre idea that when the government does it, it’s somehow a different system? No, it isn’t. We ask the question, is the government functioning like an employer? And the answer is yes, it is, and therefore there is something that Marxists have developed, the notion of state capitalism. And that’s not socialism, which is a non-employer-employee arrangement, which, by the way, has existed throughout history, and exists now in Britain, in America, in Europe, in China. It shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone, except if ideologically you can’t think your way through what I just said. Yes, so you’re talking there not only about misunderstandings of capitalism, but also of what a socialist system would look like. I want to just read a couple of things that you’ve written here. One source of the misunderstanding seems to be that, as you say, in Democracy at Work, “most of the anti-capitalist movements that called themselves socialists in the last century did not prioritize, explicitly include, or if they came to power, institute an economic system in which the production and distribution of surplus were carried out by those who produce it.” And so there are many examples of systems that call themselves socialist but don’t do what you argue is essential to socialism, that is to have democracy at work. And you say that any real socialism, any authentic socialism, is, and I'll quote you again: [...]is yearning by people living in a capitalist economic system, whether private or state capitalist, to do better than what that capitalism permits and enables, and that can mean having a work that is more socially meaningful, less physically and environmentally destructive, more secure at delivering an adequate income for yourself, having the lifelong education, leisure and civil freedom to pursue real participation in politics. Socialists want to be able to explore and develop their full potential as individuals and members of society. So these are the qualities that you think we should center when we think about what a capitalist versus socialist world would look like. Yes, but I can also be more specific, which that book tries to do, in terms of the economics. It is a way of understanding what is in this country—I don’t know how in European language this is handled, but in the United States, the closest concept that people understand is called a worker co-op, and the basic idea is that the people who come to do the work as hired individuals confront an employer, who is themselves. The collectivity of the workers is the employer. That’s how you overcome the split between employer and employee, and if you institute that, then you have gone beyond not just capitalism, but the slavery and the feudalism—because those are the three systems, unlike earlier village systems and so forth that we also know are alternatives. It’s the feudalism, the slavery, and the capitalism that are the exemplars of the dichotomy between those who make the decisions and sit at the top and who are rich, versus those who do the work and sit at the bottom who are not rich. And the socialist dream, therefore, was not just to go beyond capitalism, but to go beyond any system that incorporates that split, because that split makes it impossible to realize liberty, equality, and fraternity. Yes, one thing that Marx was criticized for, often, was not providing a clear enough explanation of what alternative structures to capitalism might look like. One of the things that you’ve tried to do in your work is fill that gap and say, well, if we’ve analyzed what this system looked like, what could alternatives look like? And give people a real picture of that. Yes, exactly. Listen, you’re making me feel very good because you’re explaining to me that I got across what I was hoping to get across. Well, I hope so. I want to hit you with the most common defense of capitalism, though, which is people might admit that it does not provide equality, and it does not provide fraternity. Certainly, I don’t think anyone would argue it provides fraternity. But even the great Adam Smith quote about the butcher and the baker kind of assumes that there is no fraternity, and we don’t need fraternity because our self-interest is going to produce prosperity for all. But what they would say is, yes, but you can’t argue against what it produces, which is prosperity, a vast outpouring of wealth. There’s often some version of a chart showing that human wealth exploded in a certain amount. I’m sure you’ve seen the chart where GDP explodes with the onset of capitalism. You say that there are billionaires next to people suffering poverty where you are in New York. But also, look at the New York of today versus New York in 1850. Absolutely. It’s a well-rehearsed, often-heard argument from a wide variety of people. So yes, I acknowledge absolutely this argument. Here’s my response. I find it a clever maneuver of the defenders of capitalism to make that argument, and the reason why I feel that way is that every one of the gains they refer to, whether it be in the diet or the work conditions or the housing quality or the schooling, whatever it is, what was unique—and that’s true in the history of England, the United States, the world today—capitalists were always against it. They had to be fought, against massive opposition, to grant any of these things. I’m going to give you an example, but there are so many that we can spend the next 10 hours doing it, but I’m going to give you one. Here in the United States—I don’t think you have this in England, or maybe I’m wrong—we have an official, legal minimum wage. The federal government started in the Great Depression in the 1930s to pass laws mandating a minimum wage. Okay, so we’ve had that since, to be exact, 1938. So, almost a century. It was passed under enormous pressure from below, from the union movement in the United States—the CIO, during the 1930s, abetted by two socialists and one communist party. They all worked together, and they threatened the president, Franklin Roosevelt, that he wouldn’t be president much longer unless he did this, and he was smart enough and understood they were not bluffing him. His political career depended on it, so he went to work, and he got the bill passed. It took him years, during which the opposition was the capitalist class of the United States. The chambers of commerce—that’s their official organization, and subgroups of them, and industrial groups of them—fought it. They delayed it. They were very successful. The idea had been around for decades. They had postponed it, blocked it, delayed it, diluted it, and finally, it passed. Okay, did their opposition stop then? Not at all. I’ll give you the latest stage. The last time the Congress looked at and passed on the minimum wage was in the year 2009, and it was then set at $7.25 per hour, which is what it is now as I'm speaking to you. So we have had 16 years of a minimum wage at $7.25. During every one of those 16 years, the price level in this country went up, sometimes as little as one or two percent, sometimes as high as nine or 10 percent, but we never raised the minimum wage. And why not? We had Republicans and Democrats in the Congress, in the White House, but one thing both of the two parties managed to do was to savage the people living on a minimum wage. It is extraordinary. Then the only thing more extraordinary than the history I’ve just summarized is the clever Madison Avenue advertising move by the capitalist who blocked it, who delayed it, who postponed it, and who minimized it, to turn around and want the rest of us to applaud them for doing it. Wow. You either have to be very ignorant of what happened, or very needy of finding an argument you can hold on to. Now, it seems like what you’e saying there is in response to this argument of all the wondrous things that capitalism has delivered that it’s claiming credit for things that it doesn't deserve. That if you look at public health, the sewer system, electrification, public education, minimum wages, workplace safety— The eight-hour day. —a lot of innovations capitalism doesn’t deserve credit for. These things occurred despite capitalism, due to the struggles of workers. I want to use our remaining time to talk a little bit about current events. You recently had an interview on Democracy Now! that actually became the most viewed clip in the history of Democracy Now! on their YouTube channel. Five million people watched this—everyone is deeply inspired by you. You were talking about Trump, and you were talking about Trump’s tariff plans, and you argued essentially that we need to understand Trump’s economic plans, Trump’s Make America Great Again agenda, as a kind of desperate and futile attempt by a dying empire to preserve its global power. One of the commenters on that video put it nicely: “the United States is like the Titanic, too big to turn, too slow to react in denial about sinking and there aren’t enough lifeboats for every passenger except the 1% ultra rich.” So help us understand. We’ve been talking about peeling back myths, helping people understand what is really going on. Trump is very much a case where a story is being told that is at odds with reality. Yes. I am far from the only person—I don’t want to leave the impression that I see it and everybody else misses it. I don’t believe that. I am one of a growing number of people. I was born in the United States. I’ve been here all my life. I’ve lived here. I’ve worked here. I’m married, I have two children, all the rest of it. I’m 100 percent an American citizen, and happy to be so. It’s not in any way that I’m unique, but even though I’m pleased that I’m now a part of a much broader—let me put it this way, because it may interest you. The left perspective is stronger in the culture of the United States today than at any time in my lifetime, and I was a student and got activated in the 1960s, etc. So I am not complaining. I am having a very good time in many ways, such as the number of viewers we’re now able to get. It’s quite a move to go from the classroom as a professor, which is what I’ve done all my life, to now being in this much larger arena—let us call it by what it is. But here’s what I would say to you. We just had a presidential election. We had three candidates, Trump, Biden, and Kamala Harris. None of them, not one of them, ever uttered the word empire, ever uttered the phrase “declining empire,” “challenged empire,” “empire at a crossroads,” anything like that. We live in a country that needs to deny that the rise and fall of the Greeks and the Romans and the Persians, and if you pardon me, the British, could be followed by the rise and the fall of this empire. What is it we think we did after 1945 with the end of World War Two? Clearly, the British Empire was finished. India just finished it off in the immediate aftermath. And what they didn’t do, the Mau Mau did in Kenya, etc. And the United States replaced it. Instead of the British pound, we had the U.S. dollar. Instead of the British Navy, we had the American dominance. So we’ve had a very nice run, really good kind of second half of the 20th century and the early parts, sort of, of this century. It’s over. It was never a question of whether it would die, it was only a question of when. Anyone with even the slightest knowledge of earlier empires would have had to understand it. But here the nation is in complete denial. And you may be much better able than I am, having lived in your society, to understand that mentality. Sometimes when I go through London, I’m involved in experiences where I shake my head and say, they still don’t want to admit that their empire is over. We are at a much earlier stage. We have more excuse for denial, but that’s all we have. We have denial. The closest we came was MAGA, in this vague notion that there was a greatness that we had to reestablish. But he’s very careful—Mr. Trump is very careful. He knows that the mass of the Americans already feel that they’ve gotten the short end of the stick in a declining Empire. They get it. They really do. It’s only the academic world, the PR world, the media, the government that need to tell a different story, and so their story—and this impacts your audience—is that the rest of the world, and particularly Europe, has cheated us, abused us, manipulated us. We’ve had weak leaders, Republican and Democratic alike, who permitted this travesty to be performed on us. And Mr. Trump, getting on the biggest White Horse he can find—trying not to fall off—trying to give the image of the leader who is going to punish the miscreants in Europe who took advantage, punish the Russians and punish the Chinese. What better way than to hit them all over the head with a tariff? What a wonderful gesture of leading. None of this will work, none of it, but he’s putting on a spectacular show, and he will be able to go to the capitalist class of this country, telling them, with justice, that this is the only way to hold on to this empire a few more years. And this is so hard for others to understand, and I have that trouble here in this country too. I try to get Americans to understand, you’re not dealing with a government that is strong. You’re dealing with a government that is desperate. And that can be very dangerous and very troubling, but to understand it, you’ve got to see it in that way. Otherwise, you cannot make any sense. Mr. Trump doesn’t understand what he’s doing. His advisors, who include people I know personally, try to explain it to him, but he is the showman, and when there’s a dispute between the show and what they tell him, he goes with the show. Look, it got him into the presidency. It’ll be stupid for him to change what he has done, and he knows it, and he’s staying with it. You argued on Democracy Now! that the story he’s telling—of being ripped off by foreigners, and how we’re going to rebuild America’s prosperity with giant import taxes, a mass deportation program, and tax cuts for the wealthy—is, in your words, completely fantastical. So as an economist, you understand that none of this can can actually work. It can’t deliver what Trump says he’s going to deliver to the American people. Well, I’m careful. I don’t believe in predictions, whether a Marxist makes them or anybody else, so I’m not going to make a prediction for you. If you were to say to me, as people have, is there a zero probability that he can come out of this, I would answer, no, it’s not zero. It’s higher than zero. It would be luck, but he could be able to somehow stave off a recession, stave off the inflation that his tariffs are bringing to us as I speak to you. He could overwhelm the retaliation that’s coming from the rest of the world and somehow pull all this off. Is that possible? Yes, that’s possible. That is possible. I could, if I had to—and I’ve done the efforts—chart out how it might. But you’re talking about a probability of a probability of a probability. And if you know anything about mathematics, when you do that, you get a very small probability—10 percent of 10 percent of 10 percent gets vanishingly close to nothing very quickly. That’s where he is. It’s a tremendous bet. But again, he’s able to say, and he is saying, to the people around him, at the top of the business community, I’m the best shot you’ve got. And the truth of it is, they believe him enough not to throw him out, and if he loses them, he’ll be gone. But I think it’s fairly safe to say that most American workers are being sold a bill of goods that they’re unlikely to [get a return on]. The true Trump agenda is enriching the richest, cutting benefits for the poorest, deregulation, cutting environmental regulations. And really, a lot of people will be deeply hurt by the Trump agenda when he promises prosperity. And look, without the working class, he wouldn’t be elected today. He has in 100 days, or whatever it is now—three months—lost a significant [amount of them]—but I don’t want to take away from him. He still has the people that like the story he tells, whose anger and upset gets worse, but their allegiance to his story also gets stronger. There is that group, but there’s another group more in the middle, and he’s lost them. If they were to vote today, they wouldn’t vote him in. I want to just ask you one more thing. You wrote a wonderful piece for the Asia Times on the economics of immigration recently, and one of the things that you said is that essentially, the story that is told by Trump and other nativists about immigration is wrong. You called it a cruel hoax. This mass deportation—that we’ll all be better off if we take all the people who shouldn’t be here and get rid of them—you said, “represents a nationally self-destructive program based on a faulty grasp of immigration economics. What once made America great was its successive waves of immigrants. What underscored the American economy’s strength was its ability to absorb and integrate these waves and create a productive melting pot.” I feel that even many Democrats today are not willing to be forceful in their defense of the contribution of immigrants. So I was hoping you could clarify for us what you think people get wrong about the economic impact of immigration. Yes, it’s an example of something advertisers know. Sometimes the best approach is not to be too close to reality because the reality defeats you. Come up with a really wildly different story that people will be willing to embrace. I think that’s what immigration is. And let me explain. The United States has 330 million people. It is one of the richest economies in the world. You know all that. The number of undocumented immigrants in this country is estimated to be maximum 12 million people. Now, in the simplest universe of analytical thinking, there is no way that a population of 12 million of the poorest people on the planet, which is what most immigrants are, are the cause of the difficulties of a population of 330 million. It’s silly. It is nuts. But that’s the genius of the argument. You take something that is so crazy nobody has ever thought of it before. We all know what immigrants do. I live in New York City. You know what immigrants do? They clean the dishes in the back of the restaurant. They work at the car wash and rub the fender of your car after the machines have sprayed the chemicals all over it. They have the worst jobs, live in the worst housing, have the worst problems, and have the worst relationship with the police. On and on. Nobody wants to have anything to do with them, and they don’t affect anything we do other than having to view their pathetic lives, occasionally, when we make the wrong turn in our automobile. That’s what the reality is. How do you make that into the cause of your difficulty? The answer is, you can’t. So you need to use language. The immigrants have—I’m quoting our president—“invaded” us. Oh, my goodness. An army of maids and dishwashers. Yes, an army possessed of a cloth in the back of your car. You know, they’re the ones who clean the bedpans in the hospital, who clean the toilets in every public facility. That’s their job. That’s what they get. And they don’t get paid well, and they get treated horribly, because if you don’t pay them properly for the week’s work that they gave you, what are they going to do? They’re undocumented. They can’t go to the police and complain. The police are the last people who’ll ever hear about it. So what do you do? You make them an invasion, then you make them into criminals. The FBI statistics show crystal clear that the rate of crime, all crime, among natives is greater than among immigrants. And for no difficult reason: an immigrant who commits a crime is in much greater trouble than a person who isn’t. All the logic has to be pushed aside. “They’re criminals, and we’re going to get rid of them.” Here’s the most important thing: over the last 40 years, the United States has become deindustrialized. I’m not sure the Europeans get this, even though you’ve had the same thing happened to you. We’re done. Ohio, Pennsylvania—all the areas of concentration of American industry are wastelands. They’re gone. And that all happened after 1970. They all went abroad, and the American working class lost their jobs, most particularly white men, because they were the ones in the unions. They were the ones who fought their battles and got the good wages. And they were the ones that were replaced when you either automated them out of existence, or you moved the jobs to China, Asia, and so on. At the same time—this is so important—that you destroyed the white male working class, you had a movement with different roots, a civil rights movement for Black people and an anti-sexism movement among women, demanding not to have the glass ceiling, demanding not to be treated as second-class. And the genius of the right wing—and I’d take my hat off if I wore one. Here’s their genius: they link these two. [They say] one is the cause, the other the effect. Your job was lost because those white women and those black and brown men took your job. The Democrats gave them your jobs, gave them programs to help them—diversity, inclusion. All of that junk is taking your job. These immigrant invaders made common cause with the evil Democrats, screwing you out of your life and your children as well. Very well done. And guess what? The Democratic Party had no idea how to deal with this, and so they developed a lame me-too-ism, which has landed them in the place they’re in now. Transcript edited byPatrick Farnsworth.Nathan J. Robinson

Richard Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff

Robinson

Wolff