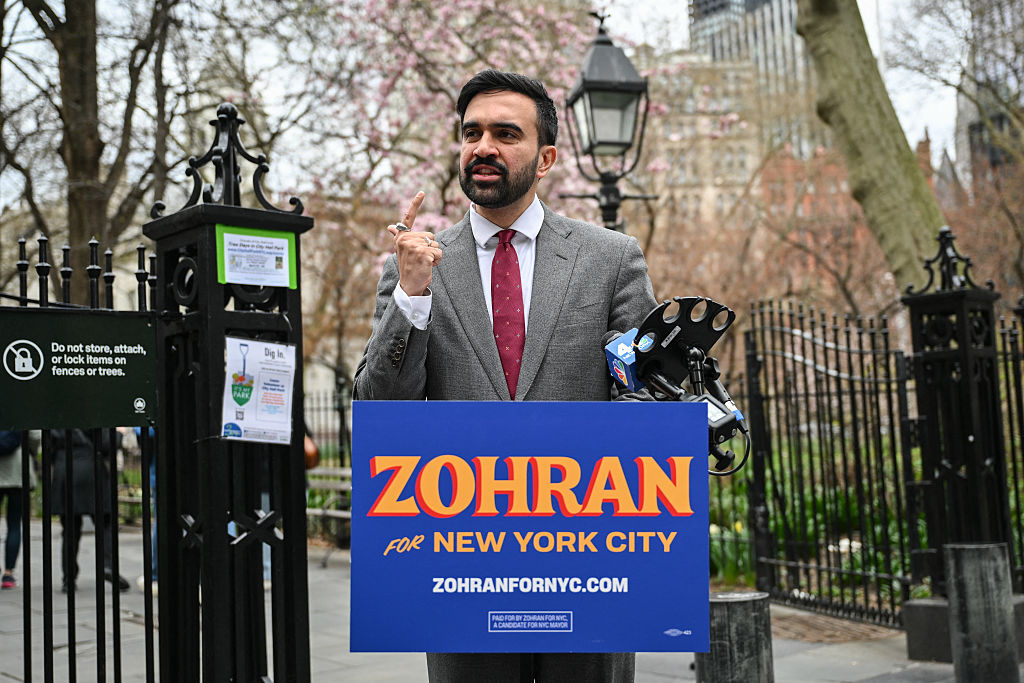

In his campaign for the mayorship of New York City, Zohran Mamdani has proposed replacing fares for the city’s buses with taxes. The reaction to this proposal has been really bizarre and mostly based on a mistaken understanding of how to think about government revenue.

Annie Lowrey neatly summarizes the conventional wisdom in her recent piece in the Atlantic where she describes the proposal as “impractical” and elaborates that “free buses would deprive the MTA of needed revenue.” Other pundits like Matt Yglesias and various commentators on transit have said the same thing.

But this is just wrong. Mamdani proposes replacing fare revenue (a user fee) with tax revenue. The MTA would have the same revenue just from different sources.

When you push people on this point, what they end up saying — with varying levels of awareness — is that they want the MTA to both have the tax revenue that Mamdani is proposing for it and the fare revenue. Because doing both generates more revenue, this proposal always wins against just doing the tax.

But this is confused. Taxes and fares are both revenue sources and ultimately they trade off with one another. Every dollar you collect in fares is one less dollar households have for paying tax. Thus, the more fares you charge, the less you can tax because you need to ensure that individuals have enough money to pay the fares.

This is a mistake I have seen again and again in my years as a policy analyst. Back during the Medicare for All debates, Kevin Drum and Wendell Primus made a version of this argument where they argued that financing our health care system with private premiums and out-of-pocket spending (user fees) makes it so that we have more room to fund government services because it makes it so we do not have to spend as many tax dollars on health care and can use those dollars for other purposes.

This is wrong for the same reason the argument against fare-free buses is wrong: having households pay premiums and out-of-pocket expenses reduces the amount of taxes a government can levy. If households need to pay $10,000 per year into the private health care system, then that is $10,000 less they have available to pay in taxes. The more you tax, the less money people have to pay health care or bus fees and the more you have people pay health care or bus fees, the less you can tax them.

In other contexts people seem to understand this. We don’t say that not charging user fees for school reduces revenue. Most people seem to realize that if we shifted to a fee-funded school system, we’d need to roll back property and other taxes in order to make sure people had the money to pay the fees (putting aside the distributive problems caused by that change). Contrary to what Lowrey wrote, using taxes rather than fees to fund public schools does not “deprive the [schools] of needed revenue.”

Interestingly, people also seem to understand this specifically in the context of buses. The largest bus system in the country, which by some estimates is larger than every urban bus system in the country combined, is almost entirely fare-free. It’s the school bus system. A modest fare — say, 50 cents a day — could raise billions in revenue. And yet, when I have pressed people who talk about the impracticality of fare-free busing, I have yet to find a single one who is willing to charge even a cent for school bus fares.

The same sort of pattern can be found with police services, fire services, and library services, among others. You could charge fees for those things, but opting for tax-financing rather than fee-financing does not deprive them of revenue.

What’s so sad about this confused discourse about revenue is that debating about when it is and isn’t good to charge user fees is actually a lot of fun and interesting. Sometimes user fees are important to manage excess demand (e.g., with electricity fees) while other times that is not so important (e.g., with fees for using local playgrounds). Sometimes distributive fairness requires the imposition of user fees (e.g., with fees for expensive food) and other times it actually requires the non-imposition of user fees (e.g., with medical devices for the disabled).

NYC had a fare-free bus pilot not too long ago and the results look quite good. There was a 14 percent increase in riders and a 30 to 38 percent increase in rides. Despite this big increase in passenger miles, pilot bus speeds did not decline any more than the system as a whole over the period. Dwell times at each stop increased, reflecting the increase in riders being boarded, but dwell times per passenger decreased, reflecting the efficiency of not collecting fares. Service performance was basically the same as non-pilot routes across a number of measures. Violence against bus drivers declined.

None of this points to the practical necessity of user fees for New York City buses. Indeed, the fact that about half of bus riders already do not pay their fare (a figure that does not include the NYC students who ride for free or elderly, disabled, and low-income residents who ride for half price) also suggests that it is quite possible to run much of the system without fares. The degree to which this suggestion has scandalized people simply makes no sense.