By Chris Schiano, Unicorn Riot

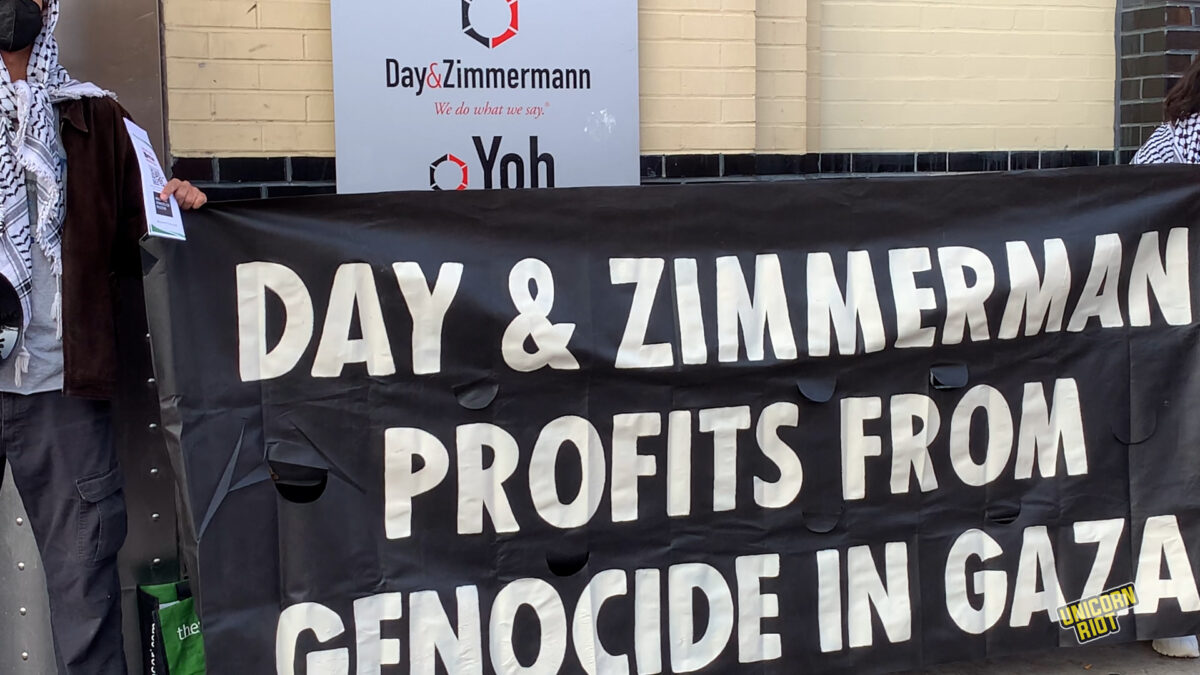

Philadelphia, PA — “Before long the entire city will know what this company does!” These were some of the last words spoken Tuesday morning by a protester with a megaphone and a kaffiyeh scarf after a few dozen people had gathered for two hours outside a well-appointed office building in Center City Philadelphia. Their target was Day & Zimmermann, a “construction, engineering, staffing and ammunition manufacture” company that makes shells and machine gun rounds used by Israel to kill Palestinians.

Employees arriving for work at the weapons manufacturer’s headquarters on June 3 found themselves greeted with banners reading “Day & Zimmermann Out Of Philly! – No Genocide Profiteers In Our Neighborhood” and “Day and Zimmermann Profits From Genocide in Gaza.“

Day & Zimmermann was previously visited by protesters in March and April 2024 who oppose its lucrative role in arming the ongoing Israeli genocide in occupied Palestine.

A new protest campaign just launched by the Philly chapter of Students For Justice in Palestine (SJP) has vowed to bring shame and attention to Day & Zimmermann every Tuesday morning.

Tuesday morning’s visit to Day & Zimmermann’s offices highlighted the role of the “genocide profiteer” in the January 29, 2024 massacre in which Israeli soldiers killed 6-year-old Hind Rajab, six of her family members, and two paramedics. An exploded shell found at the scene of Rajab’s murder was traced via serial number to the Iowa Army Ammunition Plant, which is owned and operated by Day & Zimmermann. (More info on this below.)

A Philly SJP spokesperson told Unicorn Riot,

“We’re committed to getting Day & Zimmermann the fuck out of Philly… they’re one of the country and the world’s leading weapons manufacturers… We are hoping to mobilize people against the murderers of Hind Rajab and countless other Palestinians… and kick them the fuck out.”

Philadelphia Students for Justice in Palestine Coalition

Activists chanted and distributed leaflets educating passers-by and employees in nearby businesses about their neighbor’s role in facilitating genocide and ethnic cleansing in Gaza. Several people working near the Day & Zimmermann HQ expressed shock and concern, with one woman telling protesters “y’all are doing God’s work, for real,” and remarking that she was aware of issues around the University of Pennsylvania’s investments in Israel but not of such a direct connection to her daily routine.

Clusters of protesters gathered outside the two front entrances on 1500 Spring Garden St. as well as Day & Zimmermann’s back entrance and employee parking gate by the intersection of 15th & Hamilton, where several prepared statements were read outlining recent Israeli massacres of Palestinians as employees walked by to clock in to work:

https://vimeo.com/1091031772

No arriving employees arriving interacted with any demonstrators; a building security employee briefly explained that they would not be permitted to block any entrances. Approximately a dozen Philadelphia Police, occasionally speaking with building security staff who would walk up to their cruisers, were deployed in vehicles scattered around the immediate area; a couple plainclothes officers sporting Civil Affairs Unit armbands stood closer to the building entrances monitoring the protest.

CBS Philadelphia (KYW-TV), whose headquarters is in the same building at 1500 Spring Garden, did not send a reporter to cover the protest despite their proximity. A CBS employee who spoke to Unicorn Riot on their way into work insisted that management was aware of the demonstration.

Day & Zimmermann bills itself as “a leading provider of munitions” and reportedly has over 43,000 employees in the US. The company has not responded to a request for comment as of publication time.

According to a research summary by the American Friends Service Committee, shells fired by Israeli Merkava tanks at the site of Hind Rajab’s murder and a November 2023 attack on a U.N. school had serial numbers that trace back to Mason & Hanger, a subsidiary of Day & Zimmermann for the last 25 years:

Day & Zimmermann, based in Pennsylvania, is a private munitions manufacturer. It operates the Iowa Army Ammunition Plant (IAAP), which has been the source of many of the artillery munitions used by the Israeli military, including 155mm rounds, fired by Israel’s M109 howitzer guns, and 120mm M830A1 High Explosive Anti-Tank (HEAT) round, fired by Israel’s Merkava battle tanks.

Mason & Hanger has operated the IAAP since 1951. Between 1998 and 2007, the factory was operated by American Ordnance, a joint venture of Mason & Hanger and General Dynamics. Day & Zimmermann acquired Mason & Hanger in 1999, and in 2007 it acquired General Dyanmics’ stake in American Ordnance.

In November 2023, Israeli tanks fired M830A1 rounds while attacking a U.N. school in Gaza. The serial number on one of the rounds recovered from the scene of the attack suggests that it was manufactured at the IAAP by Mason & Hanger in December 1990.

On January 19, 2024, Israeli tanks fired M830A1 rounds in an attack that killed six-year-old Hind Rajab, her six family members, and the medics who attempted to rescue her, in the Gaza neighborhood of Tel al-Hawa. The serial number on an exploded round found inside the ambulance sent to rescue Rajab suggests that it was manufactured at the IAAP by Mason & Hanger in November 1996.

In December 2023, the U.S. government used emergency measures to approve the transfer of 14,000 M830A1 tank rounds to Israel without Congressional review. The transfer—from the existing inventory of the U.S. Army–was worth $106.5 million and funded by U.S. taxpayers’ money.

Day & Zimmermann’s factory in Texarkana, Texas, is the current supplier of M830A1 rounds for the U.S. Army. Between 2017 and 2021, the U.S. Army’s supplier of these munitions was a Northrop Grumman factory in Plymouth, Minn.

American Friends Service Committee research summary

More media from Palestine in the image below.

Follow us on X (aka Twitter), Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, Instagram, Mastodon, Threads, BlueSky and Patreon.

Please consider a tax-deductible donation to help sustain our horizontally-organized, non-profit media organization:

Published June 9, 2025