I was asked to talk about resilience at an event last month organised by the architects Perkins & Will, and decided to speak to the idea of “a politics of the future”, which seems increasingly important if we’re going to navigate a world of climate disruption and psychic loss—quite apart from the practicalities of de-carbonising our societies. This is a slightly expanded version of my remarks there.

I drew quite heavily on a paper from last year by Julian White, at the LSE, called ‘The Future as a Democratic Resource’. He asks, rhetorically,

What gets lost when the future gets lost?

Imagined futures

The answer, rather starkly, is democratic politics. The reason for this is that elections within a democracy are supposed to be a competition between different parties offering differing imagined futures. (This is similar to Jens Beckert’s argument in Imagined Futures that within businesses senior managers compete on visions of the future of the organisation.)

But there’s a big hole where these imagined futures ought to be. The right tends to offer a vision of an imagined past, while centre parties, whether centre-left or centre-right, are intent on managing the present. They are focused on policy, not politics. I’ll come back to this distinction.

The research suggests that this lack of alternatives affects voting level because people start abstaining from voting, and that the more disadvantaged are the first to drop out.

Better life

And maybe there are a couple of findings from polling research that are relevant here.

The first is that people are likely to believe that other people are less concerned about climate change than they are, which reduces public pressure for political action. You have to wonder if the technocratic way that climate change and related policies are discussed in public influences this perception.

At the other end of the political spectrum, people who voted for Trump in 2016 and Brexit in 2017 are more likely to answer ‘no’ to a question about whether their children will have a better life than they did. They believe that the future is closing down on them.

Three Cs, or four

White argues in his paper that there are three benefits of a politics of the future. These are:

- Critical perspective

- Collective agency, and

- Commitment.

Expanding on these a little, critical perspective creates a distance between the present and a possible future, making it easier to imagine a different future. Meaningful alternatives also allow for a direction of travel, rather than simply reacting to events.

Creating the collective—or perhaps creating a collective—is about building a shared idea of “we”. This is something politics, broadly described, can do, but policy can’t do. Party politics will still be a form of coalition building in the conventional sense of creating collections of interests around issues. But the element of the future imagination creates more coherence.

Political prophecy

White quotes Roberto Unger as saying

Politicians need to speak in two languages – both calculations of interest and political prophecy.

The third element here, commitment, is about giving this coalition some coherence when things get turbulent. Because, if you’re going to change anything, you’re also going to end up in the “transition trough”: things will get harder and bumpier before they get better. A politics of the future allows you to ride those rapids.

So maybe there’s also a fourth ‘c’ here, for cohesion.

The ‘Abundance’ thing

Some of this brings to mind the recent book Abundance, by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. I’ve not read it, but it’s been impossible to miss it. It’s been #1 on the New York Times best-seller list, and almost every male policy-wonk in America has felt the need to write something about it.

One of those posts quoted two sentences from the introduction which they felt summarised the thesis of the book:

“This book is dedicated to a simple idea: to have the future we want, we have to build and invent more of what we need. That’s it. That’s the thesis.”

Building and inventing, broadly speaking, more houses, more (high speed) rail, more green-tech and more clean tech. It’s worth noting that the we in that quote is doing a lot of work, and for my money, this is fairly thin stuff. In effect, it’s a call for more public goods. (Nothing with that: we generally need more public goods, but we need quite a lot more than that.)

Structures of feeling

The reason Abundance is interesting to me is not because of what it is, but because what all that interest in it represents.

(Raymond Williams: structures of feeling. Photo: Gwydion Madawc Williams, public domain.)

The cultural critic Raymond Williams developed the idea of structures of feeling—which I should come back to here on another occasion—to describe changes that you could sense or feel before you could measure them.

Sometimes these appear in culture first: for example Williams describes how changing attitudes to debt in England in the 19th century were seen first in the writings of Dickens and Emily Bronte. In other words, structures of feeling signal a possible cultural hypothesis.

Testing the hypothesis

It’s also worth noting that Abundance is one of a set of US books that are about the same issue: Stuck, by Yoni Appelbaum, and Why Nothing Works, by Marc Dunkelman, are in the same policy space.

As it happens, some of the hypothesis of Abundance has been tested. The Biden administration spent $1 trillion investing in public goods under the Inflation Reduction Act, and as far as we can tell, given how things turned out, almost nobody noticed.

And the purpose here is not to spend time on a critique of Abundance, but just to note that it is a book about policy, not politics. And Ezra Klein has said as much on his podcast, when he talked to critics of his book on the American left. (He also admitted to being surprised by these criticisms, which were about the lack of politics, and political economy, in the book.) From my notes:

We should start from the policy outcomes we want and work backwards.

Cancelling the future

Because: a politics of the future needs to involve more than building. Some of this reminds me of the work of another cultural critic, the late Mark Fisher, who wrote across two different books about the cultural and political impact of neoliberalism.

In his collection Ghosts of my Life, he writes about “the slow cancellation of the future”, drawing on the work of Franco Berardi. The way I summarised this on my blog was that

the combination of the neoliberal ethos that has dominated since the 1980s and the emergence of ubiquitous ICT had closed down our ideas of the future.

The ‘Three Reals’

In the lead essay in the book, Fisher looked in particular at the cultural sense of stasis:

While 20th Century experimental culture was seized by a recombinatorial delirium, which made it feel as if newness was infinitely available, the 21st Century is oppressed by a crushing sense of finitude and exhaustion. It doesn’t feel like the future.

In his earlier book, Capitalist Realism, Fisher wrote about the crisis of “the three reals” of capitalism: the ecological crisis, widespread mental distress, and proliferating bureaucracy. (Dan Davies has returned to the last of these more recently in his book The Unaccountability Machine.)

The politics of a book like Abundance seems to try to address the first of these, but not in a way that is completely convincing—there’s a lot of building involved, and that is going to involve materials, etc. But it doesn’t start to address the psychological crisis or the sense of an outsourced bureaucracy that seems designed to ensure that we have no control over our lives.

Crises of reproduction

I’ve written about this in a chapter that’s now due to come out sometime this year. The underlying argument of that chapter is that the current extractive economic model of the city has reached its limits. It is no longer able to reproduce itself, economically, socially, or culturally. This crisis of reproduction is one of the reasons why we have no politics of the future.

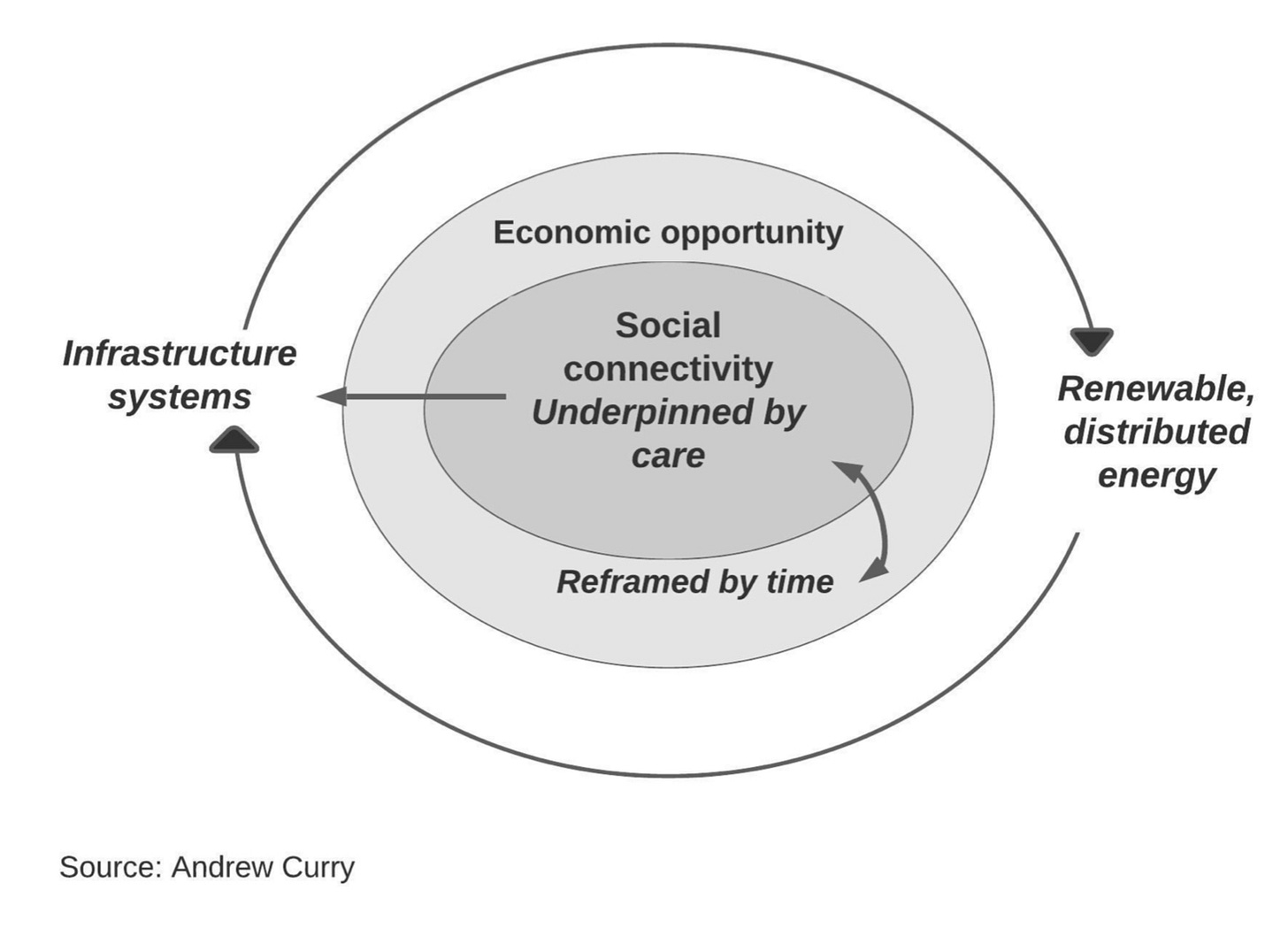

In all of this, the ecological city is a hygiene factor. A meaningful politics of the future will need to deal with the psychological crisis. So it might also involve a different politics of time—and we’re already seeing this in the innovations around the four day week. And it will need a different politics of care, and we’re not close to that yet. My suggestion here is that a politics of the future that might make a difference would be about reimagining our relationships, with each other and with nature.