“Surprising. Astounding. Staggering. Unnerving. Bewildering. Flabbergasting. Disquieting. Gob smacking. Shocking. Mind boggling.”

These are the words prominent climate scientist Ed Hawkins used to describe a global heat spike that occurred in 2023 and extended into 2024. Hawkins is known for his innovative depictions of climate data, arranging them visually in ways that deliver a visceral sense of the implications behind the otherwise dry and repetitive numbers. As such, he is probably as sensitive to the meaning of data as anyone, rendering his choice of words particularly pointed. Something big occurred in 2023 and in the wrong direction—Earth experienced a surge in heating that was gob-smackingly beyond what models predicted based on CO2 emissions alone.

What caused it? That’s still being debated. But here’s a more specific question—did our degradation of the biosphere, particularly forests, have anything to do with it?

That might be something we want to know, given our planet’s current condition, especially when you consider the critical role of of low clouds in the planet’s heat balance. Low elevation clouds tend to have bright tops which reflect sunlight back to space, helping to cool the climate at planetary scale. They’re also a signature creation of healthy, vegetated landscapes. Plants and soil not only release water vapor but cloud condensation nuclei, which together hasten the creation of clouds at lower elevations. These low clouds not only shade the land, they rain on it, bringing forth more vegetation, more evapotranspiration, more cloud-seeding and more low clouds with bright tops.

It follows then, that when you remove or damage the vegetation (what science calls “land change”) you reduce the creation of low clouds, with consequent warming. As we all know, this business of land change has been going on quite a while on planet Earth, accelerating mightily with mechanization post 1950, and then again in the 1980’s with globalization and the digital revolution. Now entire biosystems are reaching thresholds and tipping points, in danger of falling from wet to dyer states. In a 2019 editorial in ScienceAdvances, long time researchers of the Amazon rainforest declared “The tipping is here, it is now.” As it turns out, 2023 was a year of record drought for the Amazon.

Now our questions get a little more specific. Could the Amazonian drought, caused mainly by deforestation, have had anything to do with the record planetary warming. What about the fires that engulfed millions of acres of converted monocrop forests in eastern Canada? What about other land use around the globe, the clearing of land for agriculture, ranchland and cities? What about the steady harvesting of the last primary forests of not only the Amazon, but the Congo, the Boreal, the rainforests of Southeast Asia and what remains of the North American temperate rainforest, ongoing just north of me on Vancouver Island, British Columbia? How did all that effect low cloud cover?

We don’t know because such questions haven’t been asked, at least not officially or publicly, as far as I can discern. Across over 17 articles, studies and blog posts, including Nature, Science, the New York Times, Washington Post, the Guardian, and others, I encountered zero reference to living systems; no mention of deforestation, water cycles, ecosystems, soils, wetlands, or the biosphere.

This is the anomaly of the 2023 heat anomaly, that when science officially looked into the cause, the living earth and our treatment of it seems to have gotten left out.

A Hot Year Leads to Hot Debate

By late 2023, it was already clear that it had been an unusually warm year. On December 26, Raymond Zhong of the New York Times wrote a piece entitled The Earth Was Due For Another Year of Record Warmth. But This Warm? Detailing the collapse of heat records around the globe, he then turned to the atmosphere and the gasses in it, noting that while CO2 emissions, known to warm the atmosphere, had gone up, aerosol emissions, known to cool the atmosphere, had gone down as a result of regulations on shipping pollution. This was the theory being advanced by James Hansen, known as the “Godfather of climate science” for his early testimony in the 1980’s alerting congress to the dangers of CO2 emissions.

Once 2023 came to a close and the numbers were officially tallied, the New York Times ran another piece, entitled See How 2023 Shattered Records to Become the Hottest Year. Beginning “The numbers are in…” the piece listed three more possible causes—the underwater eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘a volcano off the coast of Hawaii, the El Nino phenomenon (a natural fluctuation of ocean currents that affects global temperatures) and the acceleration of ocean warming. But apparently, the explanations were still not satisfactory to scientists, as the piece concluded by quoting Karina von Schuckmann, an oceanographer at Mercator Ocean International in Toulouse, France, saying

“Something unusual is happening that we don’t understand.”

Two weeks later, NASA published their official interpretation on their website Earth Observatory, titled Five Factors to Explain the Record Heat in 2023. They listed: 1) Greenhouse gas emissions. 2) A resurging El Nino. 3) An acceleration of background ocean warming. 4) A decrease in aerosols (fine particulates that reflect sunlight) that would have otherwise cooled the atmosphere. 5) The Hunga Tonga explosion, which they determined to be insignificant.

Gavin Schmidt, Director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, then added a few more possible causes on his blog site, Real Climate, including solar variations, aerosols in China and the behavior of Sahara dusts. Schmidt also provided some personal perspective in the prestigious journal, Nature. What’s notable in the piece, is Schmidt’s acknowledgement of the the frustration of scientists trying to explain the phenomenon. “It’s humbling, and a bit worrying, to admit that no year has confounded climate scientists’ predictive capabilities more than 2023 has,” he writes. He ends the piece saying, “We need answers for why 2023 turned out to be the warmest year in possibly the past 100,000 years. And we need them quickly.” No answers came forth, though, and three months later, in August, he called for a session at the upcoming conference of the American Geophysical Union, titled “Cracking the Puzzle of the Anomalous Temperatures of 2023.”

Note the sense of bafflement, and the urgency. Note also how far the net was flung in the search for causes, entailing everything from underwater volcanos to Saharan dusts to shipping emissions. One would think global-scale land destruction and its effect on water cycles might make the list, but so far it remained unmentioned.

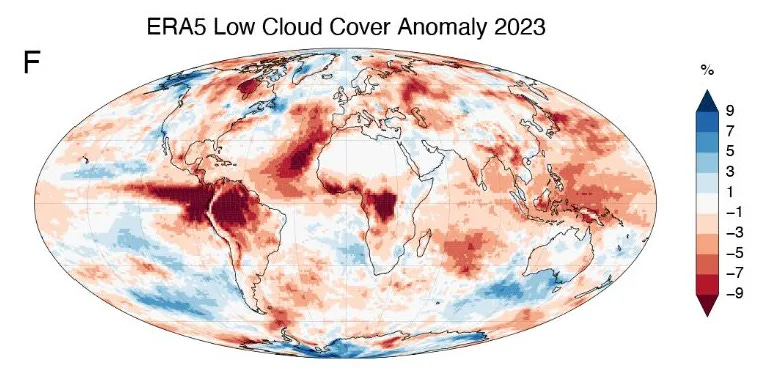

Then a new theory entered the debate. Physicist and modeler Helge F. Goessling and two other scientists released a paper in Science saying they’d found the missing cause of the heat anomaly—reduced planetary albedo (reflectiveness) “caused largely by reduced low-cloud cover in the northern mid-latitudes and tropics.” You may be thinking that a link is finally being made with the land. But actually, no. The decline is treated in purely physical terms related to CO2 warming, lower industrial aerosol emissions and large-scale atmospheric circulations.

Other scientists took notice. Theoretical physicist Anastasia Makarieva responded, “Amazon drought cries out from graphs but not mentioned in a Science paper on abnormal 2023 warming,” highlighting the following figure pulled from Goessling’s paper.

This figure (dark represents reduced cloud cover) shows profound cloud reduction over the Amazon, the Congo and the forests of northeastern Canada, all of which are under heavy extractive pressure. Indeed, in 2023 the Amazon experienced a record drought, while wildfires spread throughout the monocrop forests of eastern Canada.

Not long after Makarieva’s post, a group of eleven scientists published a group letter in response to the Goessling paper, pointing out that it neglects “the potentially critical role of forests and other land cover types…” Investments are needed, they said, “…to better understand and integrate land cover-cloud interactions and decreasing ecosystem functionality.” They concluded by calling for “action to effectively safeguard and restore natural forests whose role in regulating the climate and supporting life remains grossly underrated.”

A few months later, Makarieva and 13 associates offered similar commentary:

Goessling et al. (1) link the record-breaking warming anomaly of 2023 to a global albedo decline due to reduced low-level cloud cover. What caused the reduction remains unclear. Goessling et al. considered several geophysical mechanisms, including ocean surface warming and declining aerosol emissions, but did not discuss the biosphere. We propose that disruption of global biospheric functioning could be a cause, as supported by three lines of evidence that have not yet been jointly considered.

First, plant functioning plays a key role in cloud formation (2–7). In one model study, converting land from swamp to desert raised global temperature by 8 K due to reduced cloud cover (8). In the Amazon, the low-level cloud cover increases markedly with the photosynthetic activity of the underlying forest (9).

Second, in 2023, photosynthesis on land experienced a globally significant disruption, as signaled by the complete disappearance of the terrestrial carbon sink (10). Terrestrial ecosystems, which typically absorb approximately one-fourth of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, anomalously ceased this function. This breakdown was attributed to Canadian wildfires and the record-breaking drought in the Amazon (11).

Third, Goessling et al. focus on changes over oceans, but their maps show that some of the largest reductions in cloud cover in 2023 were over land, including over Amazonian and Congolian forests. Another cloud reduction hotspot is evident over Canada. Besides, precipitation over land in 2023 had a major negative anomaly, 0.08 mm day 1 (12).

Like the authors of the other letter, they urge “more integrative thinking and emphasize the importance of urgently curbing forest exploitation to stabilize both the climate and the biosphere (17, 18).”

(Note: Both letters and references can be found found at the bottom of the Science piece, under “Eletters.”)

Did any of this commentary make it into the media, even environmental media? Not that I’ve seen, which is not only unfortunate, but strange, considering the story potential. Here we have respected, well-published scientists asserting that degradation of the biosphere is being left out of the analysis of an unexpected rise in planetary temperatures. That’s not news? We also have this happening in the context of a global biodiversity crisis, in which the planet’s living systems are collapsing around the globe. Should that not influence the scope of inquiry?

Meanwhile, the Goessling paper was picked up by a plethora of media outlets, such as The Washington Post, Inside Climate News, and NBC News. Under the headline, Scientists Discover Explanation for the Unusually Sudden Temperature Rise in 2023, Scitech Daily displayed a flame-engulfed planet, the caption below explaining how the decline in low cloud cover was “driven by fewer aerosols, natural fluctuations, and global warming feedbacks,” with no mention of forests.

I want to be clear that I’m not challenging the results of the Goessling study or others, or the importance of understanding the many physical influences they discuss, including potential feedbacks to atmospheric warming. The climate is hugely complex. It’s what gets left out that is troubling, as it is in media report after media report. There’s a flood, yet no one asks about the condition of the soils. Could they absorb the rains? And how was the rest of the landscape? Was it healthy and intact, able to moderate the water cycle? It is the same with drought and the same with fire. What’s been done to forest over the last two hundred years? No one asks that.

This is about something deeper than individual scientists and their work. It’s about a pattern, a long-running pattern of dismissal and disinterest around the effects of land degradation on the climate. I’ve written about this before, how at one time land change, and by extension the biosphere and what we’re doing to it, had a much more prominent place in climate science. This view was displaced by a purely physical, quantitative analysis, of which our treeless conversation about low cloud cover is only the most recent, if not extreme, example.

It has to do of course with modeling. Quantitative modelling shows a marginal radiative effect of land change on global warming. In fact, things like deforestation are assessed as a mild cooling due to the reflectiveness that results from the removal of the dark green land cover. Such assessments are obviously problematic, but they are also incomplete and of low certainty, because models, despite their sophistication and usefulness, cannot reproduce the complexity of bio-hydrological processes. As Anastasia Makarieva put it in a recent presentation to the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR),

“We can’t know from models what happens to the water cycle when we deforest land. They don’t provide any guidance.”

Rather, she quotes MIT scientist Kerry Emanual posing a very interesting question: “Are we computing too much and thinking too little?” In an essay addressing what he sees as an overdependence on modeling, Emanual suggests that sometimes it’s “easier to run the model than to develop a comprehensive and satisfying understanding of the phenomena in question.” That last part bears repeating. “A comprehensive and satisfying understanding of the phenomenon in question.” Is a discussion of low cloud cover without mention of forests comprehensive, or satisfying for that matter?

Risks and Consequences

There are risks to this approach. What if the biosphere is indeed losing it’s ability to cope with CO2 emissions? What if we fail to notice because our attention is not on the biosphere but on the CO2 emissions?” What if, while waiting for modeling to get sophisticated enough to show us, or “prove” for us, what our eyes and instruments and intellects can already see, we come to understand too late?

The consequences, meanwhile, of looking at climate like this are all about us. Right now a four lane highway is being built through the northern coastal Amazon rainforest. That in itself isn’t strange; roads are being punched into forests around the world. What’s strange is the occasion—the next climate summit, COP 30. It’s meant to ease traffic for the city of Belem, when this November 50,000 people from around the world will fly in to save the climate. But don’t worry, government officials say the highway will be “sustainable.”

Thinking includes imagining. So let’s imagine if climate science had a fully functioning biologic lens. That is, it looked as intensively at living processes and their intricate moderations of climate as it does at the physics around the greenhouse effect. Would clearing rainforests to build roads for climate summits happen? Would Indonesia be clearing its rainforests to produce biofuels, considered a “green” climate solution?

There are anomalies to go around these days. Jennifer Mamola, Policy and Advocacy Director for the John Muir Project, wrote a piece the other day about a friend who, after driving cross-country. arrived with a completely clean windshield. She had never washed it, never needed to across thousands of insect-bare miles. How’s that for an anomaly.

Ultimately, beneath all these anomalies lies a common one, and it’s inside us. Or to be more specific, it’s in our heads. It’s the perception, or misperception, that we are separate from the rest, somehow above. It’s an old anomaly and isn’t unique to any one individual. And it seems to be getting progressively worse. The methods we use, and the words that come with them, seem to be widening the distance between us. What we call the climate is really the earth, and measurement doesn’t always equal understanding.

It all depends on the questions.

Teaser image credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data [2023], processed by Pierre Markuse Massive fires in Québec, Canada (Lat: 53.33, Lng: -76.11) – 28 June 2023 Image is about 39 kilometers wide. By Pierre Markuse – Massive fires in Québec, Canada (Lat: 53.33, Lng: -76.11) – 28 June 2023, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=137428491