On February 6, 2025 the leader of the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) Lee Jae-myung spoke to the Economist and confirmed South Korea’s geopolitical dilemma. Lee had been cozying up to the US since ex-President Yoon Suk-yeol was indicted and removed from office in January. Uncharacteristic of his party, Lee had expressed a willingness to work with Korea’s former colonizer Japan and continue Yoon’s Sinophobic policies. Meanwhile, Lee’s party submitted materials to nominate US President Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize, “in the hope that he continues his peacemaking efforts for the Korean Peninsula.” The absurdity of this tactic from the liberal party in South Korea documents the depths of South Korean subservience and US intervention in peninsular affairs.

Korean self-determination had been made impossible for over a century, caught in the crosshairs of US hegemonic intervention in Asia. In 1905, at the end of the Russo-Japanese War, President Theodore Roosevelt brokered the ceasefire and subsequent peace treaty that recognized Japanese power over Korea and led to its annexation. In 1906, Roosevelt – an elite New Yorker, Rough Rider, hunter, expansionist, architect of the Panama Canal, colonizer – won the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating the Treaty of Portsmouth, becoming the first American to receive this honor. Roosevelt’s style of imperialism demonstrates a historical continuation of a United States that practices peacekeeping amidst warmongering in Asia and on the global stage.

Since South Korea’s Nobel Prize recommendations in February, geopolitics in East Asia has been shifting rapidly. As the US is denying and contending with its own decline as a global hegemon, superpower, and empire, US tariffs in Asia might realign power. On March 30, China, Japan, and South Korea tentatively but jointly responded to counteract US protectionist trade policies. In the first economic summit in five years, these nations met to strategize a regional agreement to encourage supply-chain cooperation and trilateral open trade in the face of Trump’s tariffs. While the US-led global economy unravels, South Korea might use the trilateral agreement in Asia to bargain with the US to lower tariffs and demonstrate South Korea’s subservience again. US economic and military intervention in Korea continues to halt self-determinative decision-making.

Tensions on the peninsula since Trump’s inauguration have been sky high, as we inch closer to midnight. To escalate tensions further, Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru issued a joint statement to reaffirm “their resolute commitment to the complete denuclearization” of North Korea, with no mention of the nuclear weapons that the US has itself introduced, stockpiled, and of course, detonated in East Asia. North Korea has responded to hostilities with its ready and growing nuclear arsenal, deeply aware of the threats and possibilities of war in the Pacific. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth claimed the US needs to consolidate its posture against China, calling on European allies to recognize their “peer competitor in the Communist Chinese with the capability and intent to threaten our homeland and core national interest in the Indo-Pacific”, and the US is doing so, from the Korean peninsula. This is Korea under ceasefire, a permanent state of war.

Martial Law and the Ironclad US-South Korea Alliance

The US public sees South Korea as a beacon of democracy, ignoring the current tensions on the peninsula, the leadership vacuum from the impeachments of Yoon and his coterie, and of course, the “ironclad” US-South Korea alliance that continues to deny Korean sovereignty. On December 3, 2024, in the immediate aftermath of the emergency martial law decree by South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol and its subsequent revocation, US-based onlookers remarked that Americans could learn from South Korea’s effective protest culture and democracy. In an eventful six hours, the military had barricaded the National Assembly, but parliamentarians climbed in through broken windows. The 190 parliamentarians present had voted unanimously to lift the martial law decree and forced Yoon to comply. As this dramaunfolded, many posted to various social media outlets to express surprise, admiration, and urgent analysis around the mass protests that rendered Yoon’s maneuver a “martial law misstep.” The Korean example of swift anger, refusal, mobilization, and eventually, impeachment and detention was praised as a model by liberal Americans, looking for a way out of their own fascist democracy as they prepared to hand presidential powers over to Trump.

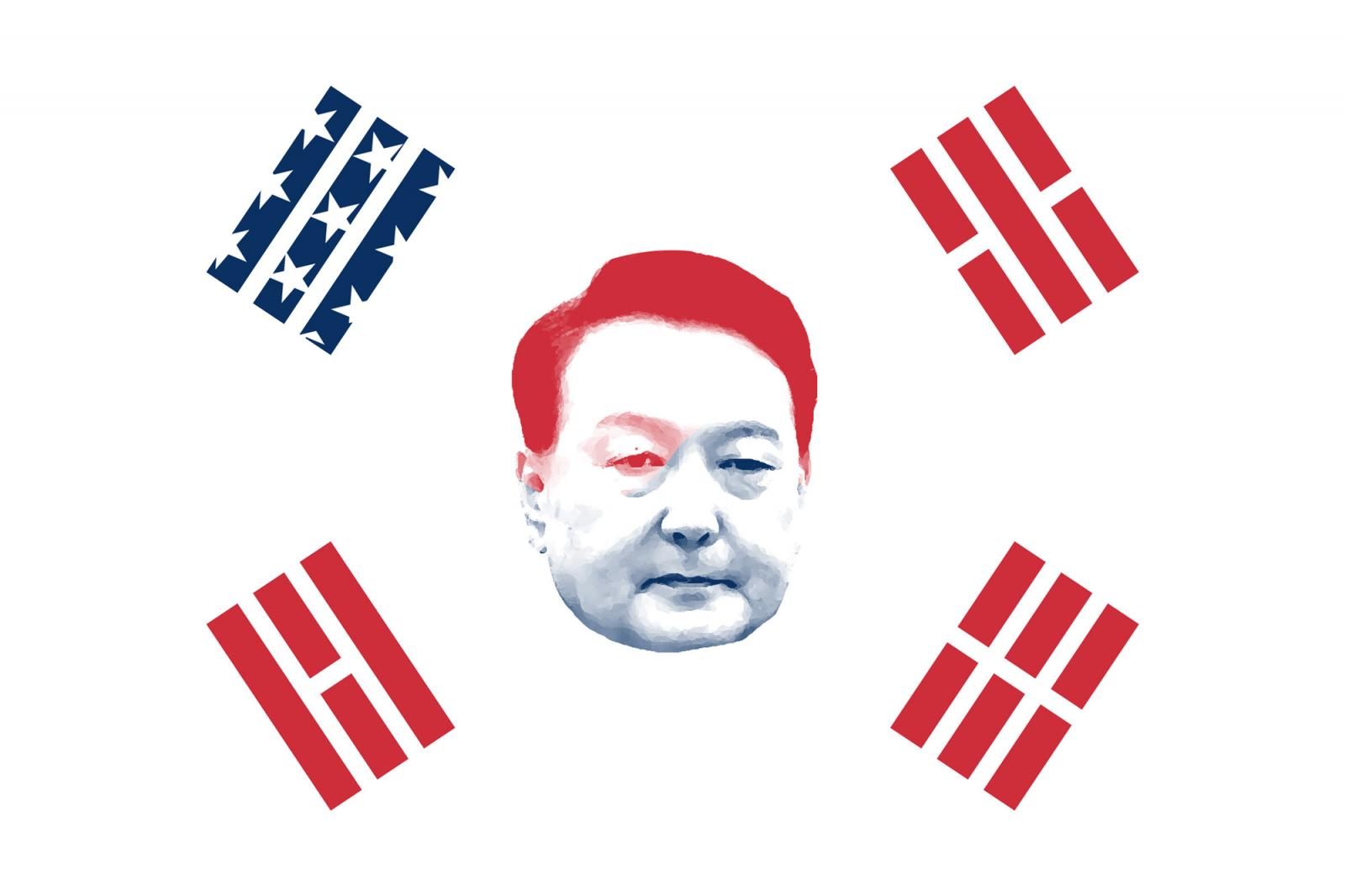

Indeed, there are parallels between the political dramas that were unfolding in the United States and South Korea. Trump and Yoon are cut from the same cloth. Yoon’s administration was hawkish, Sinophobic, anti-communist, and anti-feminist; Yoon, the First Lady, and their cronies are under investigation for stock manipulation and corruption; Yoon used the police to attack opponents, raid labor union offices, redbait leftists; Yoon mismanaged the Itaewon crowd crush tragedy; Yoon tried to shut down media outlets like Hankyoreh; under Yoon, the gap of inequality widened and workers of all kinds walked off their jobs in protest; throughout November 2024, prior to the martial law announcement, multiple protests had been drawing hundreds of thousands to the streets to demand Yoon’s resignation. Then, throughout December 2024, countless scandals that plotted assassination attempts, a “limited” war with North Korea, the plan to massacre Korean civilians, the end to Korean democratization, and the impeachments, warrants, and a presidential detention, finally led to an unanimous Constitutional Court ruling that confirmed Yoon’s impeachment. On the other hand, after Yoon’s indictment, his supporters had mobilized in protest, damaging property and storming a courthouse in Seoul. Reporters had called it Korea’s January 6th. They wielded US flags and banners that read “Stop the Steal” and “CCP Out,” invoking a pro-US and anti-China right-wing extremism that has become all too familiar in our current moment.

Neocon war hawk Bill Kristol tweeted, “In the 1980s we helped South Korea become a democracy. Now in 2024 they’re reminding us how to defend it.” The latter half especially was a sentiment shared across the political spectrum by those watching the impressive protests from the US. But by decontextualizing Korean democracy in their praise, Americans indulge their ignorance and continue a domestic legacy of ignoring the US’s role on the Korean peninsula. Throughout Yoon’s indictment and impeachment processes, Americans cited the South Korean example as a speculative fiction for Trump.

Korea’s culture of mass protest is due, in large part, to Korea’s entanglements with US geopolitics. Yoon’s governance through political repression and hawkish geopolitics aligned with US imperial ambitions, including its almost 80 year-old military occupation of South Korea. After the South Korean National Assembly voted to overturn Yoon’s martial law decree, then-US Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrote,

“We continue to expect political disagreements to be resolved peacefully and in accordance with the rule of law. We reaffirm our support for the people of Korea and the US-ROK alliance based on shared principles of democracy and the rule of law.”

Blinken did what he did best: hide US imperial violence behind the Korean people’s peaceful dissent and entrench the notion that Korea is far away from the American psyche, not an active part of the US military-industrial complex. Summarizing the molten response to the attempted coup in an imaginary peaceful and lawful resolution, Blinken recommitted to the US-ROK alliance, a military security agreement that empowers US military occupation and economic interventions in South Korea under the auspices of war against North Korea and the threat of ascendant China to US hegemony. Meanwhile, the US conducts war drills on the Korean peninsula annually. In 2024, a joint military exercise with South Korea staged nuclear deployment for the first time. The liberalism that admires the Korean spirit of peaceful dissent while upholding US militaristic hegemony is the same liberalism that occupies Korea to exploit working people, endanger the land, and violate Korean self-determination.

In Yoon, the US had found a ready authoritarian partner in South Korea to enact its goals. In 2023, Yoon had negotiated a new security alliance (American-Japanese-Korean Trilateral Pact or JAKUS), absolving Japanese colonization in Korea and conspiring with the US against China and North Korea. Since the dramas of early December, conservative think tanks and the US government itself questioned the readiness of Korea against China, as they prepared themselves for a Korean future without Yoon as president.

Amidst the uncertain government of South Korea, varying figures have tried to stabilize the US-ROK relationship. In the immediate aftermath of the first (and unsuccessful) impeachment vote in the days after the martial law announcement, Yonhap News reported that “PM [Han Duck-soo (who is now the former Prime Minister, as well as the former acting President of South Korea ] says maintaining alliance with US and trilateral security cooperation with US, Japan crucial.” Then, onto the third acting President in three weeks after the martial law decree, Choi Sang-mok recommitted to the US-ROK alliance, Yoon’s trilateral agreement, and US-led international relations. On February 16, the US recommitted its “ironclad” security commitments to South Korea and Japan, ahead of military exercises that would occur in March 2025. What is not reported in the US media is that the South Korean people had mobilized to stop a war from breaking out against North Korea.

One week before Yoon’s attempted coup, the former Defense Minister (Kim Yong-hyun) had ordered to strike North Korea, after months of cross-DMZ trash balloons and drones that the Koreas had exchanged since Yoon’s election. In February 2025, amidst constitutional crises in both nations, South Korea and the United States held live-fire drills less than twenty miles from the demilitarized zone, playing target practice on a mountainside, as part of a three-week military exercise. Then, on March 6, two fighter jets accidentally dropped eight 500-pound bombs on the village of Nogok-ri in Pocheon, South Korea, less than twenty miles from the DMZ, injuring people and damaging property and land. While live-fire drills were discontinued (and resumed in May) , the annual “war game” called “Freedom Shield” carried on as planned. As the leading labor federation in South Korea aptly assessed, such accidents would not occur if live-fire training (especially amid the unprecedented context of criminal investigations of the commander-in-chief for insurrection) was not part of normal Korean life. They argued, the accident in Pocheon is evidence for the need to stop Freedom Shield. While the White House announced plans for a “skinny budget” that would ostensibly cut all social spending, the Pentagon remains fervent in its military presence and actions abroad. The Korean peninsula is at the center of a possible nuclear war, especially as the Trump Administration moves to modify and entrench Obama’s Pivot to Asia. While US liberals credulously praise Korean democracy, Korea continues to be in a permanent state of war readiness under the US-ROK alliance. Catastrophic war is at stake under US military occupation.

Yoon in the History of US Military Rule in South Korea

Despite the narrative of the “Forgotten War,” the Korean War is not over. The 1953 armistice was intended as a temporary ceasefire preceding a peace treaty, which has yet to come amidst US interference in multiple attempts by both Korean governments. Under the terms of ceasefire, all foreign powers were directed to withdraw from the peninsula. In reality, China left, but the US remained. US popular culture, news, films, media of all sorts continue to gloss over the ongoingness of the Korean War, obfuscating the US’s role in the war’s unended status. Meanwhile, Korea is home to 62 US military bases, including Camp Humphreys, the largest US military base overseas. 28,500 troops from the US are stationed in South Korea. In 2023, war exercises on the peninsula reached 200 out of 365 days, explicitly rehearsing the decapitation of the North Korean regime. With the unimaginable and imminent possibility of nuclear power unleashed on a small peninsula in the Pacific Ocean, the only true notion of “peacetime” in Korea is a violent peace.

In December 2024, Yoon had cited “shameless pro-North anti-state forces” as justification for his martial law decree. The US intervenes in Korea to sustain a state of permanent war, division, and occupation, to protect its global dominance. Through liberal rhetoric about concerns for North Korean human rights, the US occupation in South Korea is justified to militarize villages, rehearse war in the surrounding oceans, and pollute and steal lands from the Korean people with everyday military presence on the peninsula. Yoon’s commitment to double down and demonize North Korea as justification is a political line that the US and South Korea have repeated since the founding of the Republic of Korea in 1948. Demonizing North Korea is an industry to manufacture war and peace in the presence of the US military, not new to dictatorial regimes of South Korea. The US – the most armed, militarized, carceral state in the world – weaponizes North Korea’s nuclear program, poverty, and prisons to claim US liberal superiority.

US liberal democracy underlines Korea’s history of military dictatorships. In 1979, President Park Chung-hee (who himself took power through a military coup in 1962) was assassinated, and in a battle for the top job, anti-communist liberal President Choi Kyu-hah was deposed by a military coup led by US-trained general Chun Doo-hwan. The mention of martial law reminds any Korean of the Gwangju Uprising in May 1980, when ordinary people led an armed resistance to liberate the city of Gwangju from military rule and set up the Gwangju Commune. In response, Chun led a military coup d’etat and ordered paratroopers from the DMZ to open fire, kill, and torture hundreds of civilians. On a recent 5.18, or May 18 that marks the Gwangju Uprising, my mother recounted the culture of fear during the Chun regime. With the radio reporting unreliable news, she and her siblings feared the worst, as they awaited the return of their brother to Daejeon from Gwangju. Diasporic Korean protesters in the US have underlined the central role that then-President Jimmy Carter played in greenlighting the massacre, empowering Chun to commit atrocities in Gwangju and throughout Korea, allegedly to secure South Korea from a North Korean communist takeover. The renewed threat of martial law highlights the depths of the ongoing crisis of war on the Korean peninsula and US interventionism, activating a historical memory of fear. The Korean people remember.

This winter, millions of people took to the streets to demand Yoon’s removal. Kpop idols supplied protesters with food and hand warmers in solidarity, and now, face anti-communist doxxing from Yoon’s supporters. Protesters sang, “세상을 바꾸자” or “Let’s change the world” envisioning a new Korea and contributing to a long history of mass mobilizations. For example, in 2017, the Candlelight Revolution led to the impeachment and removal of then-President Park Geun-hye. And before that, in 1987, students and laborers led the democratization movement, in opposition to the US-backed military dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan. And farther back still, in 1960, there were mass protests from student and labor groups that began the April Revolution to unseat Syngman Rhee’s autocratic, anti-communist, and pro-US regime. These mass protests in South Korea have been doing more than just deposing leaders; they have fought for Korean self-determination. In 2002, the first of the candlelight rallies were to mourn Shin Hyo-sun and Shim Mi-seon, two fourteen-year-old girls who were hit and killed by US Army personnel in an armored vehicle. Under the Status of Forces Agreement, US military personnel cannot be tried under South Korean law. Candlelight protests were as much a vigil as they were and continue to be a demonstration against the occupying US military.

In 2017, novelist Han Kang wrote an opinion piece in the New York Times, titled “While the US Talks of War, South Korea Shudders,” referring to Trump’s warmongering against North Korea. Han, who is herself from Gwangju, described her motivations for writing Human Acts, a heartbreaking study of the violence that took place under martial law in May 1980 in Gwangju.

“I wanted to ask what it is that makes human beings harm others so brutally, and how we ought to understand those who never lose hold of their humanity in the face of violence.”

She continued, “I, too, was in the streets, holding up a flame of my own…we now call it our “candlelight revolution,”” referring to the protests that ousted Park Geun-hye, who had blacklisted Han, among artists and culture workers who were critical of the right-wing government. This past October, Yoon had congratulated Han as the first Korean awardee of the Nobel Prize in literature, ironic given the connections of the 1980 and 2024 declarations of martial law. From Korea under ceasefire, Han did not celebrate, feeling the responsibility to bear witness to suffering, notably the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. In late March, Han was among over four-hundred writers who issued a statement urging the Constitutional Court to uphold Yoon’s impeachment. From the national memory of the previous military regimes, the candlelight still burns to oust US-backed authoritarianism from Korea.

Korea in the US Campaign for Global Dominance

South Korea’s democracy is a neo-colonial one. Since South Korea’s founding, eight presidents have been democratically elected, and three former presidents have been sentenced (and later pardoned) on corruption charges (this does not include the most recent criminal president). All of these corrupt presidents have been part of the US war machine, unwilling to negotiate for peace and self-determination on the peninsula. Since 1948, South Korea has declared martial law 13 times. Every time Korea has lived through martial law, US liberal democracy has worked to hide its imperial position in Korea.

The US both enacts violence and exploits South Korea into enacting the US’s imperial agenda. During the Vietnam War, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “More Flags” program hired 326,000 South Korean troops as mercenaries in a campaign of genocidal violence in Vietnam. Poet Don Mee Choi summarized South Korea’s role in Vietnam in the title of her poem “Neocolony’s Colony.” In this poem, Choi imagines the many military atrocities in Vietnam, at the hands of South Korean soldiers who were at the command of the US. She writes,

O war–breasts cut out and woman shot by ROK marines

O US marines transport her to the hospital but she died soon

Here, Choi reveals the war machine. In the “American War” in Vietnam, the US hired South Korean troops to kill Vietnamese civilians. Then, as this poem describes, the US would go on to try to save this wounded Vietnamese woman, among many Vietnamese targets, from its own war. This logic of salvation – the gift of freedom –during wartime is exemplary of US liberal fantasies.

The fight against communism in Vietnam financed South Korea, as a sub-imperial beneficiary of US empire. Choi completes this stanza,

O bonuses!

To fight in Vietnam, South Koreans were paid nearly twenty-times more than their wages at home. In exchange for the deployment of South Korean troops, the US offered a $150 million development loan, critical for Korea’s economy under Park Chung-Hee’s dictatorship.

The 2018 People’s Tribunal on War Crimes by South Korean Troops during the Vietnam War marked 50-years since some of the atrocities took place, as well as the 70th year anniversary of the Jeju Uprising, a protest-turned-rebellion against US occupation on Jeju Island in 1948 for a free and unified Korea. In response to the Jeju uprising, armed with anti-communist rage and weapons, the US military, the newly-formed South Korean government, as well as emboldened right-wing paramilitary vigilantes massacred tens of thousands of Koreans. According to the US, as they did in Vietnam with Korean mercenaries, these massacres “saved” Korea from communism.

Today, we are living amidst more armed conflicts since World War II with military capabilities to kill, massacre, starve, and erase entire peoples and places more swiftly than ever before. As the US continues to collaborate with Israel and the world continues to turn away from Palestine, war and genocidal violence rage in the Middle East; meanwhile, the US pivots from Ukraine to escalate tensions in the East and South China Seas. The machinations of US imperialism abroad are also here, in the fascist witch hunt for pro-Palestine student activists and scholars. Palestinian Columbia University student organizer Mahmoud Khalil sits in ICE detention for speaking truth to power, as the political repression mounts and keeps him from meeting his new child. Yunseo Chung, a Korean immigrant and junior at Columbia University, currently faces deportation for protesting the university’s investments in genocide, despite her legal permanent-resident status in the US. We await her trial in May, recognize the entanglements of US military outposts throughout Asia, and organize against US fascist authorities’ attempts to chill dissent. Now, as then, the US is using Korea’s strategic geopolitical position to secure hegemonic power in the face of China’s rise, to squash the possibilities of a multi-polar world. The Korean War’s unended status enables US occupation in the Asia-Pacific region, and it reverberates everywhere.

Demonstrations Against Yoon Are Demonstrations Against US Occupation

The rhetoric of peace and democracy is cover for the war economy that governs every aspect of South Korean life. Hostile US-China relations have hurt the Korean economy, as the US encourages Korea to divest from China and produce goods on behalf of the US. Now, with new tariffs against steel, chips, and pharmaceuticals, Korean and American laborers alike will suffer as the US accounts for a more desperate US empire.

In South Korea, labor organizations have been a barrier for Yoon’s unbridled campaign to build a US-centric economy. In 2022, in response to the Ulchi Freedom Shield military exercises, the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) and the Federation of Korean Trade Unions issued a joint statement – simultaneously co-signed by a union formation in North Korea – to denounce war games. The two South Korean-based labor organizations criticized then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi for provoking China on her visit to Taiwan and stating, “Another war crisis is looming on the Korean peninsula.” The KCTU, the progressive and largest labor confederation of independent unions in South Korea, holds a firm position on the necessity of self-determination and the peaceful reunification of the peninsula in the struggle against dictatorial rule. In response to this effort to demilitarize the peninsula, the Yoon government repressed and criminalized labor organizers.

March 1 marked the 106th anniversary of the Korean independence movement, a mass movement to break free from Japanese colonization. Some claimed that this movement was unrest instigated by Bolsheviks and communists. Others argued that Korea needed Japan for its modernity, infrastructural advancements, and civilization. This is the colonial logic by which the US intervenes in Korea today, claiming that the US military occupation is there to protect South Korea from North Korean Communist aggressors. Since Yoon’s indictment, the rising pro-Yoon and pro-US camp and the intense culture of redbaiting and neocolonialism have been obscured from US news outlets. On February 5, longtime activist and professor at Sung Kong Hoe University Labor Academy Ha Jong-gang had written, “The Republic of Korea is where the Red scare remains the strongest in the world.”

The political dramas that have unfolded since Yoon’s impeachment is evidence that liberal democracy’s investments in US imperialism protects ascendant authoritarianism, both in the US and South Korea. The US liberal audience that praises Korean democracy hides what the Korean people are fighting for – self-determination, an end to US military occupation, an economy that centers working people.

Korea’s future remains uncertain, and under Trump, the geopolitical context of US hostilities against North Korea and China will play out in Korea. From the eyes of the US public, the drama of martial law and its revocation might be over or irrelevant. On April 5, the Constitutional Court upheld Yoon’s impeachment (his criminal trial is forthcoming), and South Korea is headed towards a snap election. But immediately after this ruling, the news expectedly ran stories about the need for the next South Korean president to work with and alongside Trump, especially in relation to the recent imposition of tariffs and the impending global recession.

As we approach the June 3rd election in South Korea, liberal party candidate Lee Jae-myung seems to be the front-runner, as the conservative party scrambles to restore its reputation and political platform in the wake of impeachments, scandals, criminal proceedings, and plot twists. Trump, the economy, and peninsular politics have dominated South Korean election talking points. Lee’s liberal platform demands a cautious approach to Trump’s tariff negotiations; while the more leftist candidate Kwon Young-gook argues for the need to eliminate exploitation and inequality; meanwhile conservative opponents are looking to stockpile nuclear weapons to arm the southern part of the peninsula against the North.

With South Korea’s history of presidential dramas, there are bipartisan proposals to demand accountability through a constitutional amendment that would allow the reelection of a president to serve a second term (in South Korea, presidents are limited to serve one five-year term). What Yoon’s martial law decree demonstrated was South Korea’s intense political culture of militarization and violence, imposed and reinforced by US military occupation, that cannot be solved with a vote. Demanding accountability through elections is a liberal fantasy. We know this, because we have seen that Korean sovereignty cannot be elected. It is now up to the Korean people to unseat the ruling class and finish what was started under colonial rule and ceasefire: self-determination and an end to the Korean War. It is time for the “US out of Korea!”