VIEWPOINT MAGAZINE

JANUARY 17. 2023

If we sustain the distinction – as we try to throughout this book – between “politics” (understood as the battle for power) and the experiences in which processes of the production of sociability or values are at stake, we can distinguish then between the political militant (who founds their discourse on a certain set of certainties) and the militant researcher (who organizes their perspective on the basis of critical questions concerning these certainties).

Today, when the term “militant research” is regularly used in academic articles and texts, it is worth returning to the question of the purpose and practice of research militancy. Ultimately, as Hipotesis 891 highlights, research militancy is not primarily about another way of doing research, or least research that assumes academia as its main site of enunciation. Rather, it is about another way of doing politics, that does not follow a predetermined line or presume to know the answers a priori, but that sees research as part of the political process itself.

DECEMBER 5. 2022

A dossier tracing Robert Linhart's approach and commitment to militant research through new translations of texts spanning the late 1970s to the 2000s.

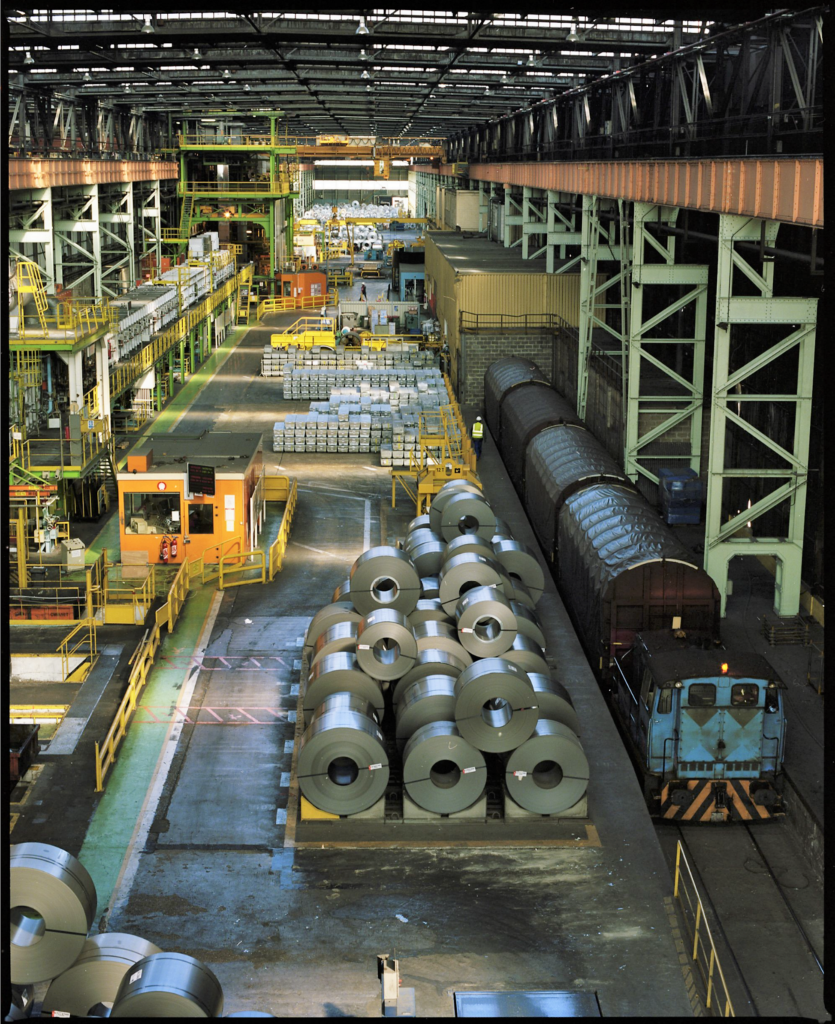

In the concrete organization of labor existing in the field, we encounter a combination of different modes of workplace organization developed up to the present moment, a combination that is the result of employer policies, working-class practices and resistance, economic factors external to the internal organization of the labor process, and various elements of the class struggle in society. It is critical, then, to not be limited to a mode of workplace organization that, at each given moment, occupies the forefront of the ideological scene, but to take into account the totality of the real organization of labor, to the extent that one can grasp it or reconstruct it.

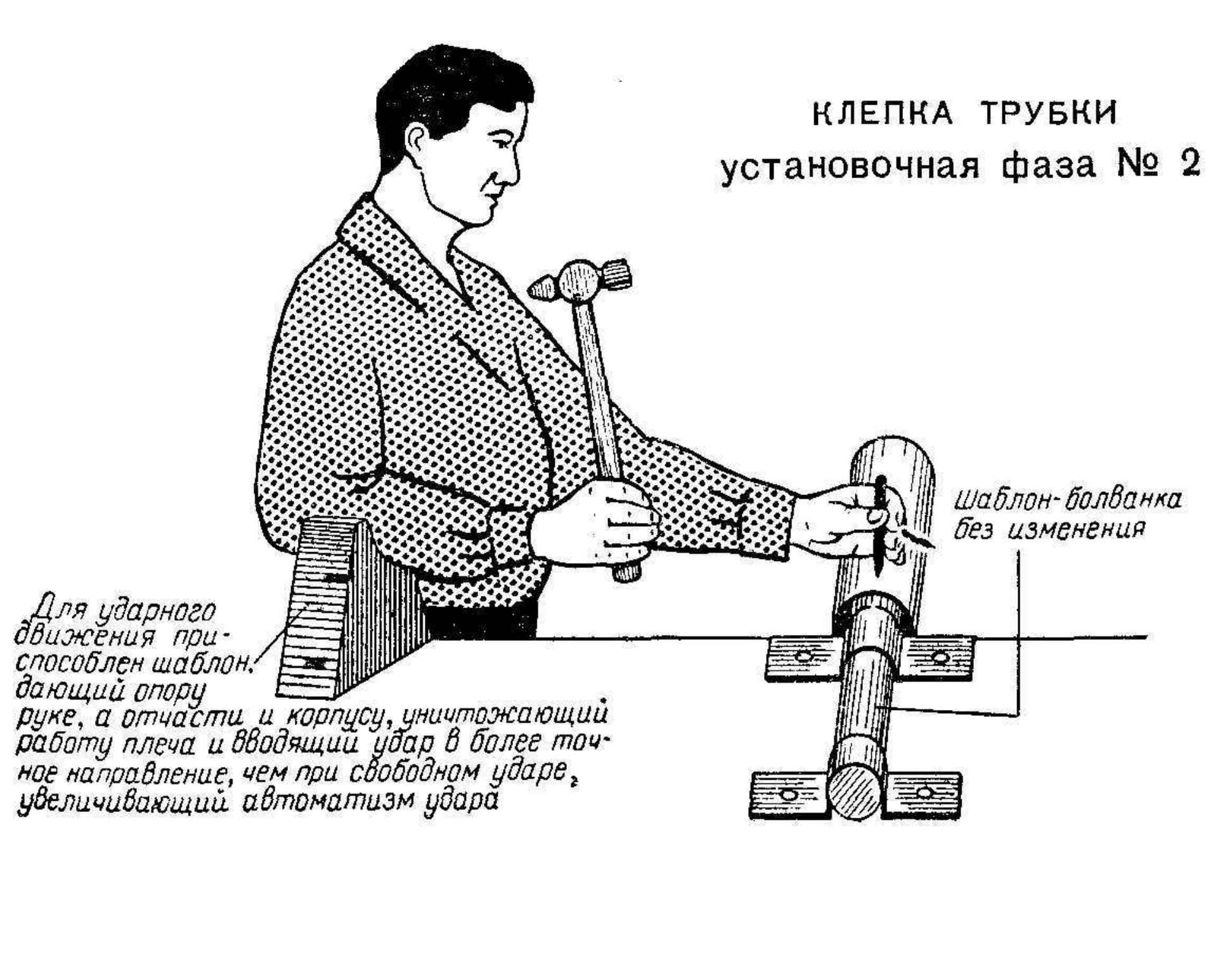

If we want to understand something, I think there’s nothing to do but go see it oneself and to patiently collect the most direct knowledge possible. Go see the sites of production, speak with workers and businesspeople, engineers, work where possible together with workers, participate directly in production. This patient work of identifying reality as concretely as possible is what I call “making inquiries. ”

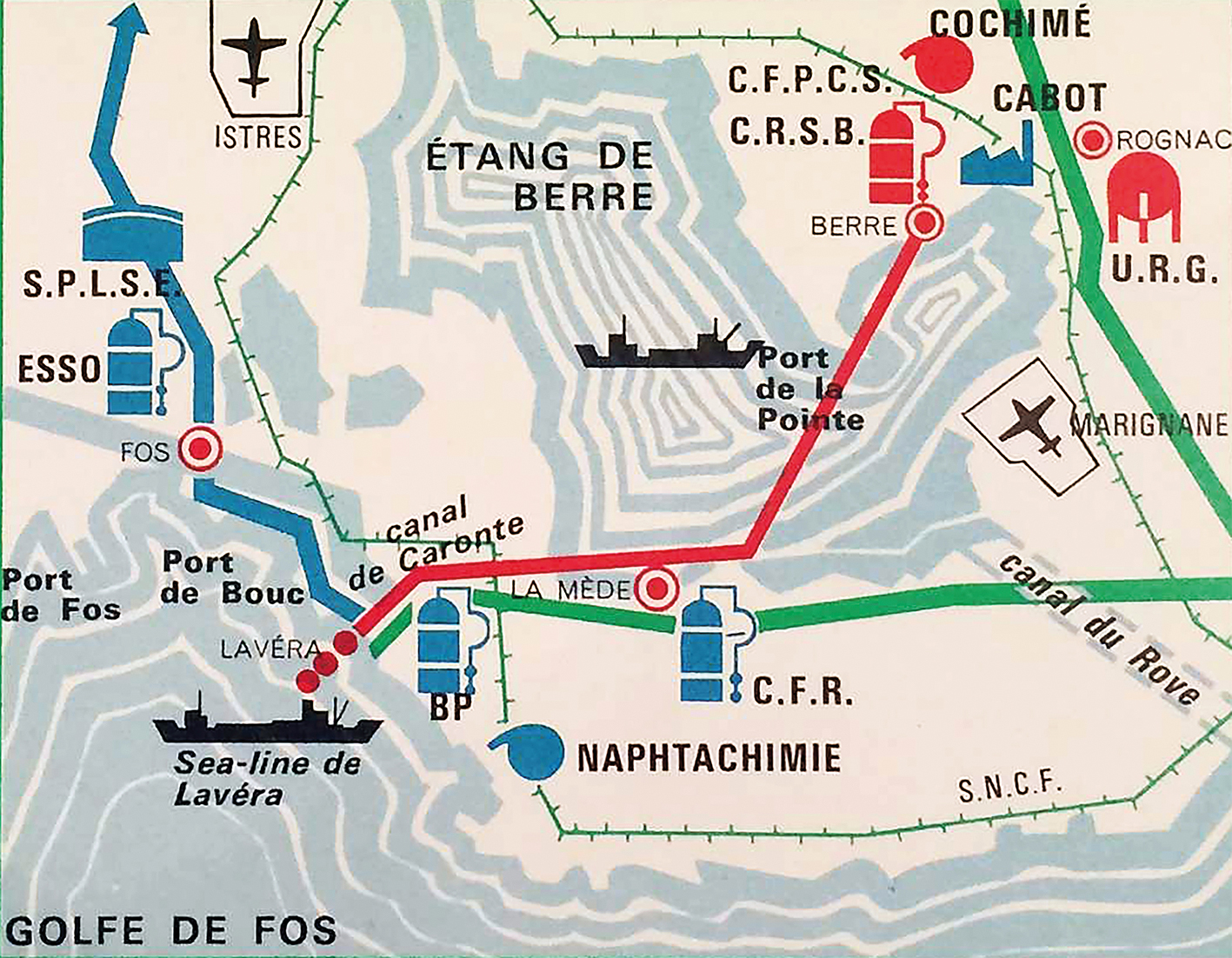

The development of outside firms permanently employed across the cluster effectively transforms the division of labor in a thoroughgoing manner, more or less insidiously changing the function of workers of the petrochemical enterprise, and in many cases coming to load the position of the working class in this sector with ambiguity – posing a problem (more or less assumed) to industrial and trade union action.

In these very difficult workplace situations, all the agents interviewed indeed stressed the importance of the group. The existence of a genuinely solidaristic and very active work group functions as a shock absorber for those temporal tensions and multiple dilemmas that are the daily lot of full-time staff on the razor’s edge.

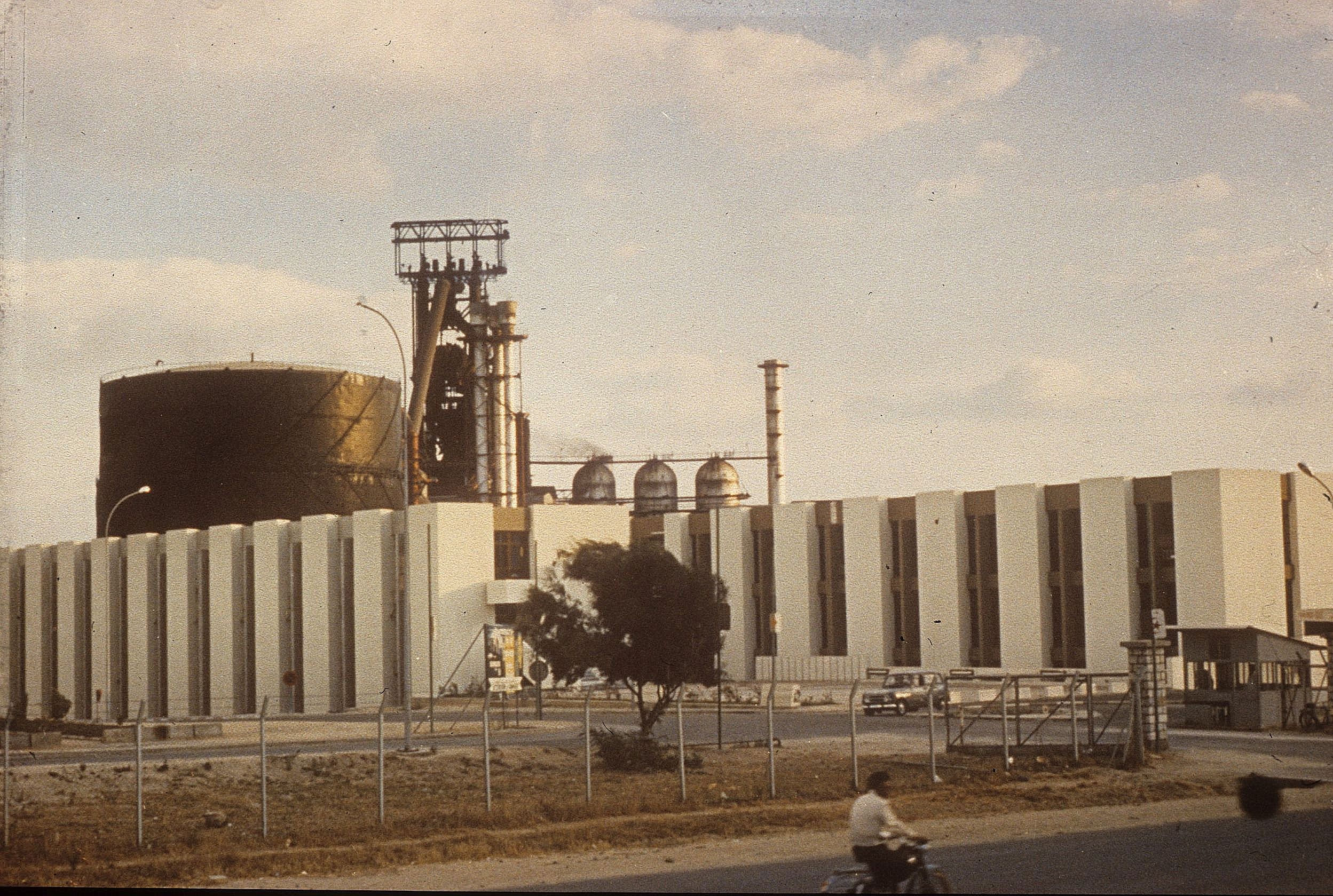

The concrete functioning of those industries which have been "offshored" or set up by "transferred technology” in Third World countries has hardly been studied in a systematic way, and we only have scattered and disparate data on this subject. It is regarding this concrete process that we would like to make a few remarks. The contradictions at work in the process of industrialization in Algeria are far from having produced all their consequences.

In the present context, what we are seeing does not really resemble the establishment of innovative organizations breaking with the Taylorist logic, but much more a mixture of genres where innovations are introduced but within a logic that remains fundamentally Taylorist. Management is engaged in a constant project to seek out another mode of control, domination, and coercion of employees before preparing the passage toward possible reforms of the organization of labor which could be rendered more compatible with the demands for responsiveness imposed by the market and new forms of competition.

Consistent with his rejection of a romanticization of the working class, Linhart insists that workers’ knowledge is fragmented and partial, if also profound. The task of the inquiry is, thus, to collect via dialogue and participation, this disjointed state of collective memory and oral testimony in support of a systematic understanding of the whole.